The bows of our sea kayaks part clear waters. A jumble of boulders lurks beneath, descending from the cobble beach ahead. To our left a rock face plunges into the depths, gripped by tenacious old cedars and gnarled pine, permanently bent against the prevailing wind. Behind is open water, wearing shadows cast from scattered clouds. With distance they blend with the blue sky and fade into the horizon. It feels like we’re paddling into a Group of Seven painting. And maybe we are.

Following the path of the Group of Seven

The Group of Seven made eight trips to Lake Superior’s North Shore between 1921 and 1928, producing hundreds of paintings. This affiliation of pioneering and adventuresome artists are famous for the unconventional ways in which they traveled—scrambling untracked summits, portaging sketch boxes over forgotten canoe trails, boarding in railway boxcars-cum-studios— and for the way they rendered the Canadian landscape. The Group’s work during this period resulted in renowned pieces like Lawren Harris’ North Shore, and Arthur Lismer’s Sombre Isle of Pic. By capturing the wild spirit of these distinctive yet little-known landscapes, they did more than simply create art, they helped develop an appreciation for wilderness in the national psyche.

While I am contemplating the role played by the Group of Seven in charting the course of Canadian art, I have to admit that, at the moment, I’m more concerned with my growling stomach.

I’m traveling with Naturally Superior Adventures on a guided sea kayak trip billed as Group of Seven Landscapes. I joined our group of paddlers at the mouth of the Auguasabon River near Terrace Bay, jumping into a double kayak with Otto Bedard, assistant to lead guide, Jen Upton. Otto is in the stern seat, cheerfully doing the bulk of the paddling while I wield my camera, documenting the kayaking voyage that will take us about 140 kilometers down the coast. We’ve been working our way between the Slate Islands and the mainland coast, taking advantage of the calm and sunny weather that has been a rarity on Superior this summer. With the cobble beach in our sights, I’m sensing a lunch stop.

A love of the land

Paddling into Group of Seven landscapes is not our primary motivation. It’s a love of skirting along Superior’s sometimes turbulent, sometimes calm, union of land and water in tiny boats that is the common denominator among our group.

Fellow guests Harald and Carol first met on a trip with Naturally Superior Adventures around Michipicoten Island in 2013, and the sixty-somethings have met annually for a Superior kayak adventure ever since. Harald is a laid-back and confident paddler who shows his respect for Superior through a traditional offering of tobacco. Carol works out regularly at the gym to maintain her remarkable paddling stamina for the express purpose of paddling the big lake. Guides Jen and Otto embrace the sun, rain, wind and fog with grace and acceptance while keeping us fed, warm and safe.

Whether we realize it or not, we share a connection with Canada’s premier landscape painters. In the words of the Group’s spokesman, Lawren Harris, “The work of the Group of Seven grew from a love of the land.”

Our trip corresponds with a resurgence of interest in the Group and their time in Algoma and the North Shore of Superior. Jen’s laminated reference materials on the artists and their works add a whole new dimension to our journey as we paddle through known painting sites like Jackfish, Port Coldwell and Pic Island.

Painted land

Perhaps the most accessible vehicle of rediscovery is a new film by White Pine productions, Painted Land: In Search of the Group Of Seven. Co-producer Michael Burtch says art historians have always acknowledged the role that this landscape played in the formation of the Group.

“They looked at Algoma and the North Shore as the catalyst for their idea of North. It represented what Canadian art should be and they painted in a style that honors the primal forces of nature, rather than in some formula derived from Europe,” Burtch explains. “And it changed the course of Canadian art.”

Burtch can trace the film’s beginnings back to 1982 when he became curator of the Art Gallery of Algoma in Sault Ste. Marie and took a ride up the Algoma Central Railway (ACR) with Dennis Reid, chief curator of the Art Gallery of Ontario. The ACR tour train follows the same rails ridden by Group of Seven members and passes obvious painting sites like J.E.H. MacDonald’s Solemn Land near the Montréal River trestle and Harris’ Waterfall at Agawa Canyon. “We thought, wow, if someone could get out there and have a look around, they could start pinning these down fairly easily,” recalls Burtch.

Burtch began dabbling in identifying painting sites, a process that intensified when he became involved in the Coalition for Algoma Passenger Train’s first Group of Seven Train Event in 2007, celebrating the Group’s work along the ACR. When Burtch retired in 2008, he had time to search for less obvious painting sites, but his wife Linda pointed out that he ought to partner with someone who could keep him from getting lost in the woods. Enter adventurers Gary and Joanie McGuffin.

In addition to knowing their way around woods and waters—intimacy they share through their exquisite coffee table books on Lake Superior and Northern Ontario and pictorial paddling manuals—author and wilderness photographer Joanie and Gary McGuffin have become champions of conservation. The trio set out to find the actual Northern Ontario locations that inspired the Group Of Seven and some of their most iconic works, for what they envisioned as a book project.

“Our goal was 100 paintings and we are so far in excess of that…we have an embarrassment of riches,” says Burtch of the Algoma and North Shore painting sites, from which more than 400 paintings have been identified.

The book is still in the works but the endeavour also expanded in 2013 into a film project. After 20 days of filming over two seasons, Painted Land was released October 2015. Burtch says the most significant discovery of this whole project is that the iconic Canadian scenes painted back in the 1920s are still very much intact.

“It’s so rare to be able to go to any part of the world and see where painters were painting almost 100 years ago,” he says, “where it’s still relatively pristine.”

The disappearance of Pic Island

The chance to see the landscape as the artists did a century ago is not always as first imagined, especially when dealing with Lake Superior. Although sunny and warm early in our voyage, a prowling fog dogs our armada of kayaks as we hug the shoreline of the Coldwell Peninsula.

“It’s right over there,” says Jen, pointing towards an impenetrable union of water and fog. We’d seen the lofty contours of Pic Island from a distance, but now that we are within a kilometer it remains enshrouded, save for a brief moment when the fog thins high overhead to reveal the faint outline of a precipitous shoreline towering 650 feet above lake level.

Our hope was to circumnavigate the charismatic landmass that inspired iconic paintings by Harris, Lismer, A.Y. Jackson and Franklin Carmichael, but the fog and forecast for strong west winds means we’ll have to stick close to the mainland instead.

On a sand beach near Foster Island, tents are pitched and we optimistically hang wet clothing on tree branches to dry. Jen and Otto exercise their culinary skills and Carol maintains a driftwood fire. Tetra packs of wine emerge from the recesses of kayaks and the fire, food and fog deliver a comfortable weariness that only comes after a long day on the water. We’re envisioning waking up to a clear dawn and a vision of Pic, but in the morning we launch into fog and paddle on without ever seeing the Island.

When I relate this story to Gary McGuffin, he laughs. “I can show you other paintings that Lawren Harris did from the exact same vantage point as where he painted Pic Island,” says McGuffin. “But he painted all the other islands surrounding it, because he couldn’t see it.”

How we see the Superior coast depends on the season, the light and the abrupt and dramatic shifts in weather. This is confirmed by our experience at Pic Island and the fact that it was painted by no fewer than four members of the Group of Seven, resulting in a dozen unique renderings.

From a busy place to a lonely place

It’s not only the weather that is constantly changing on Superior. Despite its timeless quality, the coast we’re traveling was once a much busier place. As the nose of our kayaks hit the sand beach at the old town site of Jackfish, a deeply rusted bicycle frame resting on the rocky bluff above hints at an active past.

What began as an isolated fishing village in the 1870s would change abruptly in 1884 when the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) pierced the wilderness. A hike along the beach reveals what’s left of a coal tower where more than 300 men once worked loading coal cars bound for points along the CPR line. Just down the rails are the remains of a 30-foot-high water tower, and farther along a cluster of small houses nestles at the base of a granite bluff. Roofs are caving in and empty window frames look out across the track at a wide peninsula jutting into Lake Superior.

Otto and I continue to climb up a road and out onto a rocky bluff. Old chimneys and foundations betray the location of the main town site that included a general store, two churches, a school and about 30 homes.

The town’s fate was sealed in the 1940s when the CPR began switching from coal-fired steam engines to diesel. The last coal steamer left the dock in 1948, and by the mid-1960s the devastating effect of invasive sea lamprey on the fishery meant nets were hung up for good. While the buildings are gone, the distinctive landscape as painted by Carmichael, Jackson and others, remains.

Echoes of the past also resonate within the fiord-like confines of Port Coldwell. Like Jackfish, Coldwell began as a fishing port and serviced the CPR line in the days of coal before being abandoned with the decline of the fishery.

A.Y. Jackson, in particular, was captivated by the Coldwell Peninsula. It had “a feeling of space, dramatic lighting, the stark forms of rocky hills and dead trees,” he noted, and beyond, “Lake Superior, shining like burnished silver.”

Our arrival in Coldwell coincides with the return of the sun, beaming down on the twisted remains of an ancient boiler and crane once used for loading vessels. Although the carcass of a long-retired fishing boat rests along the shoreline, there is no obvious evidence of the tall icehouse that figures so prominently in Lawren Harris’ Icehouse, Coldwell.

The story of Jackfish and Port Coldwell is the same one highlighted by Joanie McGuffin in Painted Land, “The story of the passage of time, from a busy place to a lonely place.”

Conserving what we have

With Painted Land well received and the book project underway, Burtch and the McGuffins continue to discover new painting sites. Gary McGuffin sees it as a way to add value to the region and its wilderness. Their work on the Group of Seven project is part of a broader goal for Algoma and the North Shore.

“It’s a conservation message, that’s really what it’s always been for us,” he says. “In a sense we’ve used the Group of Seven to fulfill our commitment to conservation and wilderness preservation.”

The McGuffins are also working with First Nations and North Shore communities on hiking trail and water trail development. “We are blending the artistic experience of the Group of Seven with the cultural interpretation of the landscape of the Pic River First Nation who’ve been here for 12,000 years,” says Gary.

The idea is to create an economic shift that will replace industrial development like mines and mills with eco and cultural tourism. As Joanie sums it up, “To get people back out on the land.” The McGuffins envision people working in an experiential tourism industry so strong that they will turn their noses up at any industrial development that might threaten it.

“It may seem like a lofty goal,” Gary admits, “but that’s where we’re going.”

As we paddle out of Coldwell, the sun pokes holes in an encroaching cloudbank, throwing shafts of slanted light onto wave-worn granite. The mercurial nature of the big lake presents an infinite well of discovery. Add the history of its past communities and the role Superior played in articulating the voice of Canadian art, and more fathoms are added to the well. As we paddle on to our next campsite, my thoughts mirror Gary’s closing words in Painted Land, “It’s worth honoring, worth protecting, worth letting the world know what a special place this is.”

If you go…

When: July–August offer the best chance of fair weather and moderate winds.

Where: Launch at Rainbow Falls Provincial Park’s Rossport Campground, or at the Auguasabon River boat launch in Terrace Bay, Ontario, and paddle east to take out at the harbor in mining town, Marathon. Or continue south to Hattie Cove in Pukaskwa National Park.

Outfitter: Naturally Superior Adventures offers fully guided and catered sea kayak trips throughout the North Shore, and can also arrange shuttles.

James Smedley is an Algoma-based writer, photographer and avid paddler. Watch THE CANOE an award-winning film that tells the story of Canada’s connection to water and how paddling in Ontario is enriching the lives of those who paddle there. #PaddleON.

James Smedley is an Algoma-based writer, photographer and avid paddler. Watch THE CANOE an award-winning film that tells the story of Canada’s connection to water and how paddling in Ontario is enriching the lives of those who paddle there. #PaddleON.

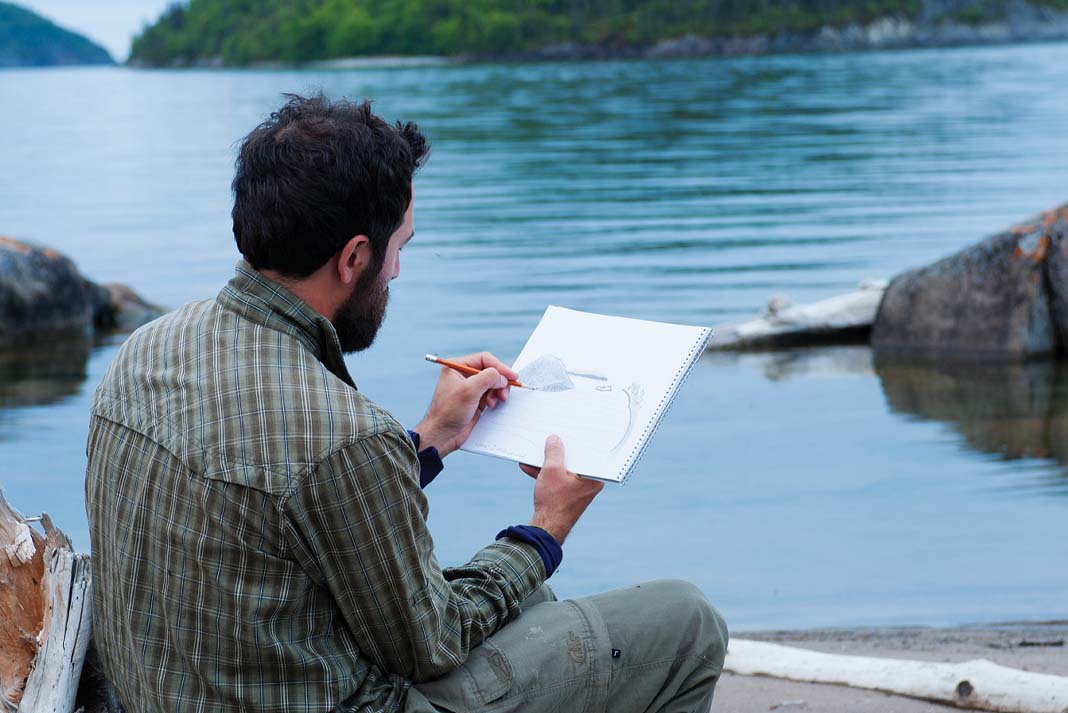

The Lake Superior landscape at Jackfish inspires assistant guide, Otto Bedard, nearly a century after these same silent hills and moody waters captivated the Group of Seven. | Feature photo: James Smedley

This article was first published in the Spring 2016 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.

This article was first published in the Spring 2016 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.