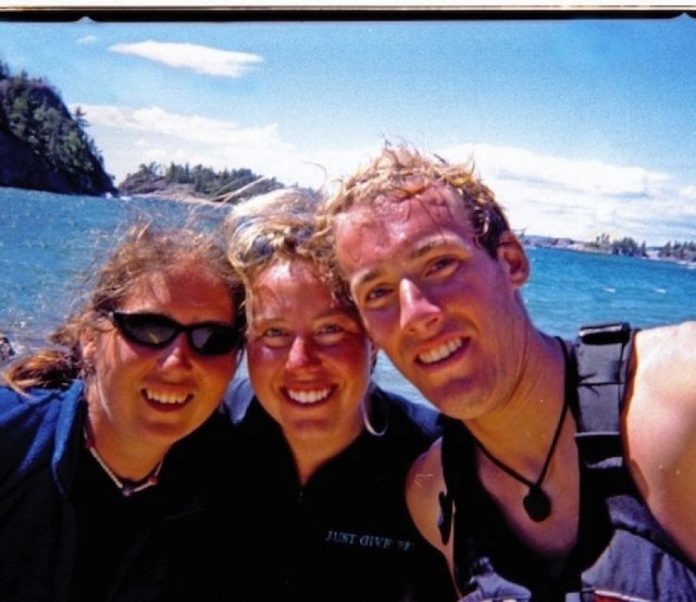

They’re not scientists, lawyers or full-time conservationists, yet these three paddlers have charted courses through wilderness protection, tumped long portages through dam relicensing, and urged the public to dip their paddles in the turbulent, challenging waters of environmental protection.

Kate Ross

PORTLAND, OREGON

After working as a kayak guide and instructor, Ross volunteered to help organize the Clackamas River Cleanup. The cleanup grew and she became a founding board member of We Love Clean Rivers, which helps others orchestrate river health events. She eventually parlayed this experience into a job, going from paddling instructor to the Outreach Coordinator for Willamette Riverkeeper. At WRK she gets people on the river and advocates for the river’s health. She won the Outdoor Industry Women’s Coalition First Ascent Award in 2011 as an emerging conservation leader.

Words of Wisdom “Make the river accessible. Traveling on the river is much more intimate than standing next to it, and people become exponentially more

committed to protecting rivers once they float them. We provide boats, organize shuttles and make it easy for people to experience the river.”

Jay Morrison

OTTAWA, ONTARIO

Morrison retired from the Canadian government at 57 and spent two years paddling across Canada. In 2003, looking for something to get involved in, he joined the board of the Canadian Parks & Wilderness Society, where he chairs the volunteer-driven campaign to protect the Dumoine River. He spends untold hours doing the non-glamorous work of river conservation: meeting with first nations, user groups and agencies, and testifying at hearings. The Dumoine has received interim protection, and he thinks they’re on the verge of a permanent win. Wondering whether his young daughter will have clean air, water and wild places after he’s gone keeps him motivated.

Words of Wisdom “Believe it or not, conservation is actually easy. Don’t be intimidated. Environmental groups need skills of all kinds and you probably have valuable skills you’ve developed elsewhere. Join a group, get involved and you’ll learn how to do it from professionals.”

Charlie Vincent

SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH

An engineer by training, Vincent led river trips with the University of Utah. Talking about the Green and Colorado rivers forced him to hone his knowledge of ecology and environmental impacts. He volunteered with American Whitewater in one of the most notoriously byzantine environmental processes: representing them in Federal Energy Regulatory Commission dam relicensing processes. His background as an engineer was a good match for the FERC process, and despite the multi-year relicensing process, they were able to secure flows for improved habitat and river recreation.

Words of Wisdom “It’s surprising how much impact you can have on the process. Maybe not at the first or second meeting, but it happens if you carve out the space and stick with it. If I’d known how long it would take, I might have been scared off, but I’m glad I wasn’t.”

– Neil Schulman is a paddler, writer and co- founder of the Confluence Environmental Center, which develops future environmental leaders.

This article was first published in the Summer/Fall 2012 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.

This article was first published in the Summer/Fall 2012 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.