John Fullbright got the call just as his family was walking in the door. He’d been in the kitchen all afternoon, preparing homemade chicken soup for his wife and daughters, who had spent the day in Denver.

Fullbright hung up the phone and told his family he was going on a rescue in the heart of the Lower Taos Box. Now, in the dead of night.

He poured some dinner into thermoses, loaded his Jackson Nirvana and 80 pounds of piñon firewood, along with sleeping bags, warm clothes and lights—plenty of lights. Fullbright took all the headlamps he could find, plus a 3,200-lumen Ridgid job site light and every tool battery in his shed. Then he left to meet his river partner, John “Copper John” Nettles.

Inside the daring night rescue mission to save two paddlers in New Mexico’s Taos Box

In their years doing river work for Taos County, New Mexico, Fullbright and Copper John have recovered the bodies of 22 people, all but one of whom had jumped from the Rio Grande Gorge Bridge, which spans the canyon some 650 feet above the river. Fullbright had known many of the jumpers. Some were good friends, one a 14-year-old boy he’d mentored. Hell, Fullbright had been to the bridge himself, years ago, intent on ending his life.

Sheriff Steve Miera stopped him that time. Parked his cruiser in the middle of the span and asked Fulbright if he was okay. He wasn’t, not by a long shot, but he didn’t jump that day. “I realized the only way out of this pain is through,” he says. He went home to his family, fought through the fog of Lyme disease, and ran the Lower Box again and again. More than anyone, he reckons, except Copper John.

When the sheriff called, they agreed the rescue couldn’t wait for morning. They’d have to go that night.

Sydnie Keeter and Jeremy “Daisy” Norris met through Trailmate Connections, an Instagram community for outdoorsy people. Daisy was new to Taos and Syd had just started grad school at Texas Tech. Daisy invited her to Taos and she drove out the next weekend.

“I guess I’m a bit reckless that way,” she says. “If you tempt me with an adventure, I’ll show up.”

Daisy wanted to explore the Rio Grande and Syd had a pair of inflatable paddleboards. Daisy raved about the river, which led Syd to believe Daisy knew something about it. Daisy made the same assumption about Syd, who, after all, owned two paddleboards.

“It was like the blind leading the blind,” Syd says.

October 26 was a gorgeous fall day, the temperature climbing toward the high 60s when they put on about 10 a.m. Syd wore a Mountain Hardwear sun shirt, leggings and river shoes, Daisy a sun hoody under a windbreaker and sandals. Neither brought a life jacket.

Syd started downstream seated on her inflatable board with a double-bladed paddle. Daisy followed, also seated, using a SUP paddle. It was Daisy’s first time on a standup paddleboard, and it showed.

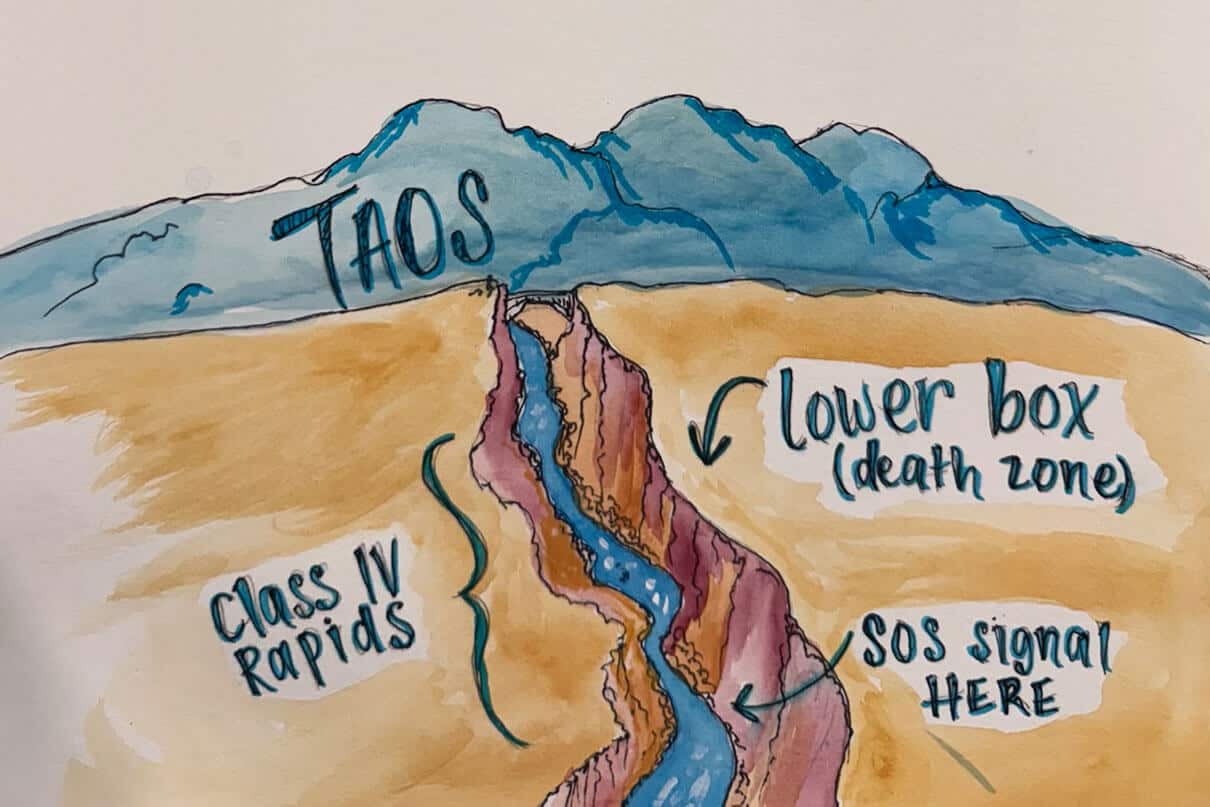

The first riffles come where the canyon narrows just below the high bridge. Daisy flipped in that rapid and nearly every one that followed. The Lower Taos Box is about 15 miles long with dozens of class III and class IV rapids, its sheer red walls towering some 800 feet above the river.

Syd and Daisy didn’t know how far they’d gone or how much farther they still had to go, but they saw the sun sinking toward the canyon’s southwest rim and felt the afternoon’s warmth leaving the air. About a mile below the bridge they came to the biggest rapid yet.

Later, Daisy wrote about their decision to run it. “Syd turns with her teeth clenched and eyes going a little wide, probably mirroring mine, and asks what I think. I think we’ve just got to get to the bottom of the Box before we’re really in trouble. All these words make it sound considered, understood. But I do not understand shit.”

The rapid was Yellowbank, “where the bodies get stuck when they jump the bridge,” Fullbright says. “It’s super sievey.”

Daisy went first over the horizon line, clutching the board until it nosedived, broached momentarily on a broad-shouldered rock, and disappeared. Syd scanned in vain for Daisy, who recalls being sucked down fast, the water “whipping me through a mess of rock and white and incredible icy force.” When Daisy surfaced 50 feet downstream, Syd was already in the water.

They came up on opposite sides of the river. Both boards were gone, never to be seen again. So were Daisy’s sandals. Somehow, Syd had managed to hold onto her water bottle and a small dry bag containing a few bites of bread, some Basque cheese, and their cell phones.

That was it. No dry clothes or matches. Neither Syd nor Daisy had told anyone where they were going.

“Daisy’s barefoot. We’re both soaked to the bone, and we’re trying to strategize by yelling over the sound of the rapids,” Syd says. “And I said I’m going to send an SOS.” Both had iPhone 15s, which can make satellite SOS calls when out of cell service.

Syd began to climb, clambering over rough red boulders and jumbled scree until, finally, the phone showed a satellite in range. Following the phone’s instructions, she sent a distress message that reached Taos Central Dispatch. Within minutes, the message was relayed to Sheriff Miera, then to Fullbright and Copper John.

It was 7 p.m. The race was on.

The sun was below the canyon rim and the air temperature fell fast. Syd and Daisy continued downstream on opposite sides of the river, thinking perhaps they could reach a trail before it was too dark to continue. Finally, Syd called across the river in the twilight. They would have to spend the night in the canyon, and they needed to be together to have any chance of surviving. Daisy, feet bleeding and shaking with cold, dove into the frigid black water and swam furiously.

Beyond the rim, the rescue operation was already taking shape. As Fullbright and Copper John prepped for a night run of the Box, the Taos County Sheriff’s Department used an infrared-seeking drone to locate Syd and Daisy in the canyon, then sent a helicopter to confirm their location. The chopper hovered low, raising spray from the river and bathing the pair in its powerful spotlight. Daisy thought the helicopter would drop a basket to whisk them both to safety. Instead, it flew away.

They would have to spend the night in the canyon, and they needed to be together to have any chance of surviving. Daisy, feet bleeding and shaking with cold, dove into the frigid black water and swam furiously.

The paddleboarders huddled together, sitting back-to-front, one damp sun shirt pulled over two shivering bodies. The temperature was dropping fast, toward an overnight low of 33°F.

Loading their boats at the put-in, Fullbright marveled at the depth of the darkness of the new moon. He and Copper John had each run the Lower Box hundreds of times, usually together, frequently at levels others deem too low. Still, neither man had run the Lower Box at night, let alone a night so dark as this, and Fullbright hadn’t been in a boat since rupturing his bicep tendon three months before.

When the sound of approaching whitewater became too much to ignore, Fullbright stopped to tape his job site light to his helmet, then blazed ahead. Copper John followed in his heavily loaded ducky. Every so often Fullbright rolled in and out of an eddy, sweeping the big light’s beam downstream to give Copper John a snapshot of what lay ahead. In this way they made their way through Yellowbanks and a dozen lesser rapids.

Daisy saw the lights first, playing on the sheer canyon walls. They watched for a minute, then shouted as the boaters came into full view. As the kayaks touched the bank at about 1:30 a.m., Syd braced for a reprimand. She and Daisy both knew they had made a long series of critical mistakes.

Despite their almost incomprehensible lack of preparation, neither was new to the outdoors. Daisy had thru-hiked the Pacific Crest Trail twice, and Syd is an avid hiker who enjoys podcasts about search and rescue. They knew they had messed up and that Fullbright and Copper John had put their own lives at risk to get to them in the middle of this moonless night. But instead of a lecture, Fullbright bounded up the beach, hollering “What’s uuup!”

They soon had a fire blazing. Syd and Daisy pulled in close, eating Fullbright’s homemade chicken and rice soup chased with hot chocolate, down sleeping bags tucked to their chins. Fullbright kept the fire going all night, telling stories like only a true river guide can.

“He’s a bullshitter in the best way,” Daisy would write later. Still, Fullbright’s tone was serious when he told them about Mountain Man, who had driven up from Alabama with a lake canoe, paddled class II every day for a week, and decided he was ready for the Box. He pushed off alone on an October day and wrapped the canoe in Power Line. He came ashore soaking wet. The temperature that night bottomed out at 10°F. The next day Fullbright and Copper John found him where he’d frozen to death, within shouting distance of where they were sitting now. That was six years ago, almost to the day. Fullbright and Copper John had been waiting for live bait ever since.

At first light, BLM river rangers started downstream in a 12-foot paddle raft. By the time they arrived, Syd and Daisy’s body temperatures had recovered. They could paddle out on the raft, walking around a few rapids, which became bigger and more complex as they neared the take-out.

At the last rapid the river pours over a shelf of boulders and plunges 10 feet. “There is no way we would have made it through this,” Daisy recalled thinking. “I can’t wrap my mind around how fortunate we are.”

Fullbright was feeling lucky too. After all the body recoveries, the chance to save two lives felt like pulling a winning lottery ticket. He’s hopeful the notoriety of the rescue will add momentum to efforts to improve swiftwater rescue training for Taos County first responders, place permanent belay anchors to make body recoveries safer, and add signage at the John Dunn put-in warning of the perils downstream.

That’s all it would have taken, he says. “Just go upstream. It’s all flatwater, and it’s beautiful.”

Jeff Moag is the former editor of Canoe & Kayak magazine. Debrief deconstructs paddling accidents and the lessons we learn from them, and celebrates those who save the day.

Feature illustration: Sydnie Keeter

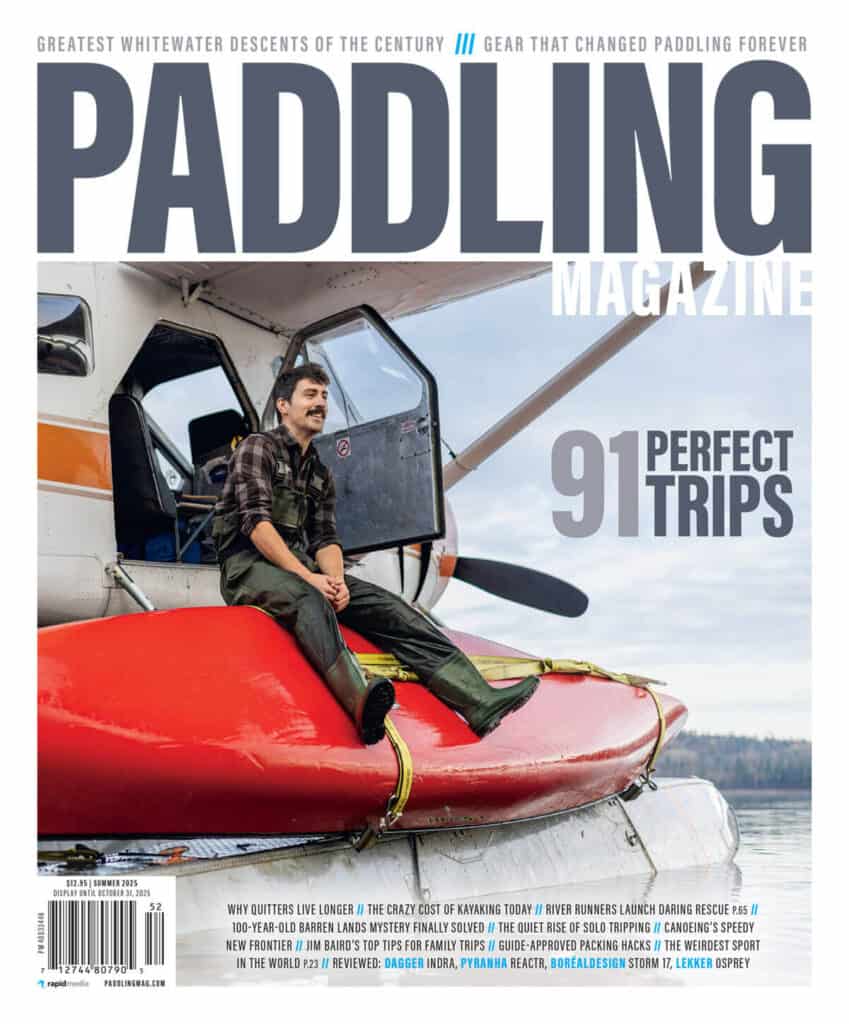

This article was published in Issue 74 of Paddling Magazine.

This article was published in Issue 74 of Paddling Magazine.

I’m surprised there aren’t any permanent belay anchors. I feel like we’re pretty good about that elsewhere in the state, but maybe that’s a false sense of security. Let me know if there’s anything I can do to help make that happen. Selfish motivation.