“I feel like my insides have been rewired.”

This is just one of the strange and bewildering things my wife, Tory, has said to me in the months after I convinced her to sign up for an introductory whitewater canoeing course. I keep replaying the experience, trying to figure out what happened and where this new person came from.

Blazing paddles: How my wife overcame her fear of whitewater

Both Tory and I were campers and guides at canoeing camps growing up. When we first met, the fact that we both understood the subtle ins and outs of canoe trip culture was one of the early revelations of our compatibility—I remember how she scrutinized me washing the dishes, being careful not to get food or soap in the lake, and smiled her approval.

When we got married, I automatically assumed we would go on to be one of those adventurous families who did whitewater river trips. I used to be a whitewater canoeing instructor, so surely I could bring the family onside. There was just the small matter of Tory being deathly afraid of moving water.

Eventually I learned the source of her trauma was decades old. Tory attended an all-girls camp that only ran flatwater trips. One of the male guides decided to break the rules and take the girls, with zero skills, down a river in their Grumman aluminum canoes. She was terrified. The guides insisted it was all “no big deal.” Tory came away convinced whitewater paddling was an inherently out-of-control activity pursued by rule-breaking cowboys.

When we had kids, Tory was not impressed with my intention to embark on rivers with our young family. She imagined launching our innocent children down the lip of a raging torrent, fingers crossed, while I yelled, “Everything will be fine!” She steeled herself to be the bulwark between me, the cowboy, and a tragic outcome.

“This is the greatest!”

Fast-forward several years and I had all but given up on changing Tory’s mind about whitewater. But last summer, as we were looking for a cushy adult vacation to do while our kids were away at overnight camp, I timidly suggested we could sign up for one of the five-day whitewater “learning vacations” offered by Eastern Ontario’s renowned Madawaska Kanu Centre (MKC). I reminded Tory that, yes, there would be whitewater involved, but the course checked many of our must-haves: outdoor activity during the day, relaxation at night and somebody else to cook our meals. Plus, there was a sauna.

Somewhere between the words relax, meals and sauna, Tory was in. I vowed to take a back seat and let her have her own experience.

As the course date approached, Tory grew increasingly anxious. She said things like “I hope this wasn’t a mistake” and “My goal is just to stay out of trouble.” It felt like after 15 years of talking about paddling whitewater together, something significant was about to happen, but I had no idea what. We both tried to keep an open mind and shrug off any attachment to the outcome.

What did happen was this: Every time I saw Tory on the river or at the end of a day of paddling, she looked a little more comfortable and relaxed. Tory said her instructor, Naomi, listened to all her concerns, gently encouraged her without pushing her, and let her choose whom she paddled with.

We laughed when we discovered the backgrounds of our two instructors. One was studying to be a social worker. The other was in the final years of a residency in psychiatry. You couldn’t have asked for better qualified teachers to help work through the whitewater traumas of one’s youth.

On top of that, it seemed like the whole culture of whitewater was the opposite of what Tory remembered and expected. There’s a well-known tradition at MKC where you get your name on the wall if you can surf a notorious local hole while spinning your paddle over your head and yelling, “Ich bin der beste.”

“That means ‘I am the greatest’ in German,” one of the instructors, Ralph, explained. He was proposing changing the phrase to something more in line with MKC’s inclusive philosophy and the spirit of modern whitewater culture, which Ralph said has evolved away from men competing and showing off—today the culture is about being welcoming and fun, and involves cheering everyone on the river.

“How about changing it to ‘This is the greatest’?” suggested Tory.

Ralph lit up. “I like that,” he said. “That might be just the thing.”

Next thing we knew, we’d glided across the eddyline and plunked straight into the trough of the wave. The stern of the canoe kicked up like a bucking bronco.

Earlier that day we’d had a “this is the greatest” surf experience of our own. For the last day of the course, Tory and I decided it was time to paddle together.

“You want me to do what?” Tory asked. We were coasting up an eddy beside a massive breaking wave our instructor had suggested we try to catch to jet ferry across the river.

“I’m not sure I’m ready for this,” Tory said warily, as I prepared to sprint upriver onto the wave. So I changed tack.

“Let’s just ease up toward it, don’t paddle hard. We’ll just slip into the current and see what happens,” I suggested.

Next thing we knew, we’d glided across the eddyline and plunked straight into the trough of the wave. The stern of the canoe kicked up like a bucking bronco. Tory belted out the kind of out-of-control scream she usually reserves for careening downhill on cross-country skis.

A moment later, the wave spat us out on the far shore—we were dry but exhilarated.

“Can we do that again?” Tory asked. Her eyes were on fire with an excitement I hadn’t seen in ages. It was one the most beautiful whitewater maneuvers I’d ever done. I’m sure if I’d charged at the wave as planned, it wouldn’t have gone nearly so well. How smoothly things can go if you don’t push too hard.

A whitewater cowboy earns her spurs

Within a week after the course, we were back at MKC, cash in hand to purchase the very canoe we’d paddled on that wave. And we brought our two kids, ages 11 and 13, for a one-day whitewater course to prepare us for the French River trip Tory had planned instead of our usual family flatwater vacation. We’ve already signed up for another week at MKC this summer.

I joke that my master plan succeeded—I finally converted Tory to whitewater paddling. But there’s an irony. Although I had a selfish motive, Tory got so much more out of the experience than I did—came away, in her words, “transformed.” Hardly a week goes by that she doesn’t talk about how excited she is to go paddling again.

“It’s amazing. How often do you gain ground as an adult? So much of getting older is about things you can’t do anymore,” she told me recently. “The beautiful thing about canoeing is, it’s actually something that ages well.”

But, I wanted to know, what changed for her, after so many years of resisting whitewater?

“I was running out of excuses, because the kids are not babies anymore,” she admitted. “You can’t close yourself off to things just because of ignorance, you know. It’s not a good way to go through life.”

I wondered, what could I do at age 50 that would stretch me as much as whitewater stretched her?

“How about a course on public speaking,” Tory joked. “Or learning to be empathetic.”

“Ha ha,” I said with a wince. “Maybe someday.”

But not yet. First there are more rivers to paddle.

Tim Shuff joined the team as assistant editor of Canoeroots for the second-ever issue of the magazine in 2003. From 2006 to 2010 he was the editor of Adventure Kayak.

All cowboys get bucked off from time to time, but what matters is that you get back on the horse. | Feature photo: David Jackson

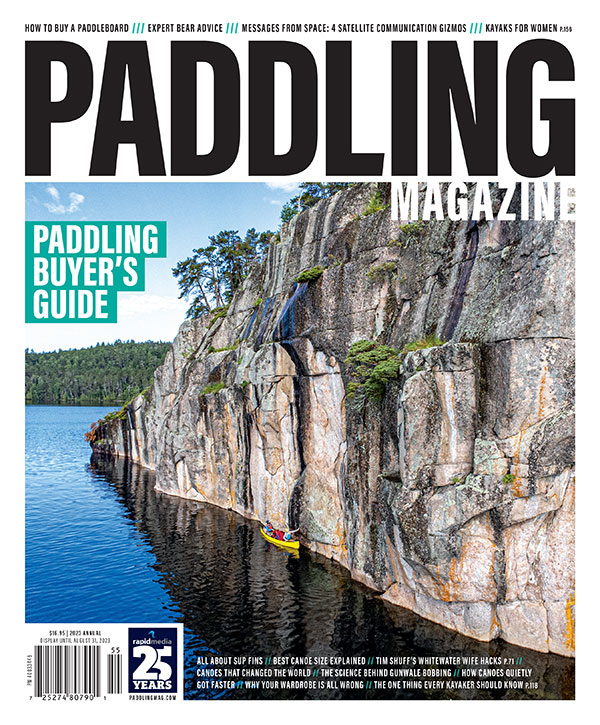

This article was first published in the 2023 Paddling Buyer’s Guide.

This article was first published in the 2023 Paddling Buyer’s Guide.