Last summer I took my family on a three-week trip. Getting our minivan to the take-out needed a shuttle. I called the only game in town and braced myself for the quote, sure it would be several hundred bucks.

“That’ll be eighteen twenty-six,” they said.

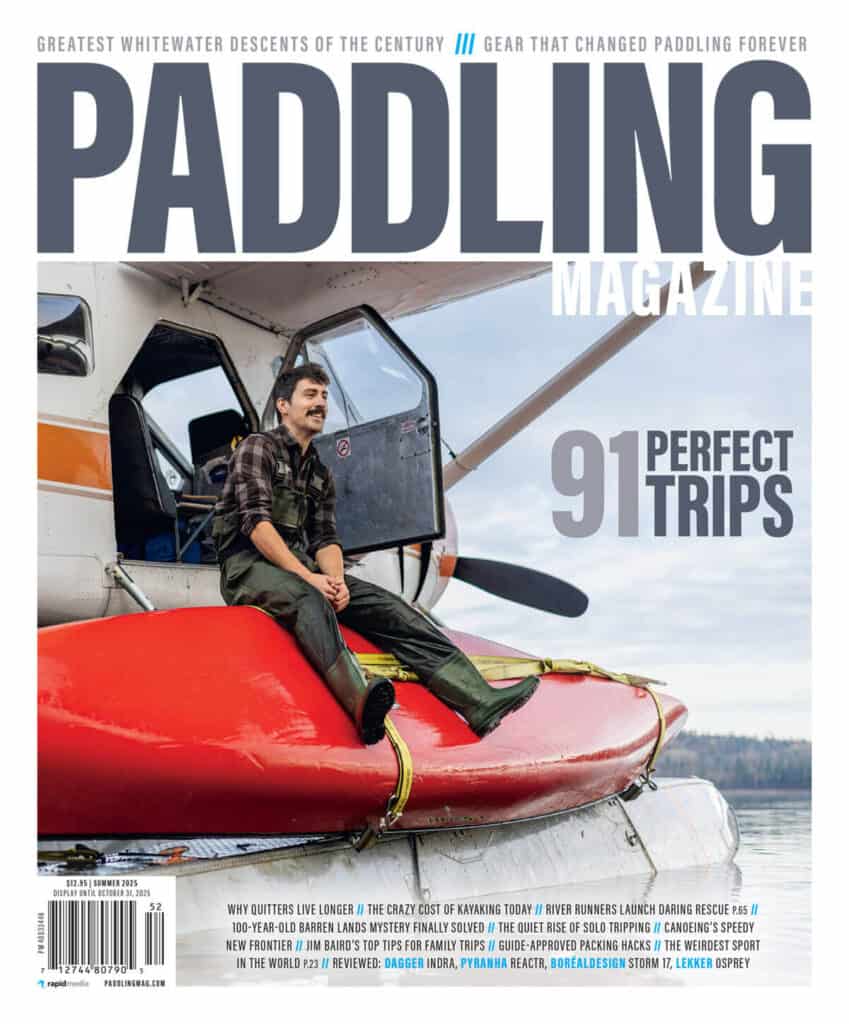

Seems awfully cheap—and oddly specific. Must be some sort of hourly rate, I thought. Then it dawned on me: $1,826! Did I accidentally ask for the floatplane charter?

That was just to get us on the water. Park fees totaled $500. And it could have been more. Car camping starts around $50 a night and climbs from there—for a square of dirt with pit toilets and noisy neighbors. That used to be the price of a motel.

Has kayaking gotten too expensive?

After the shuttle and permits, we still bought hundreds of dollars worth of freeze-dried food. Plus, a $400 satellite beacon with a monthly subscription for safety. But as a family vacation, it was still relatively affordable because I already owned all the equipment—kayaks, paddles, tents and other gear I’ve spent my whole adult life accumulating. I can take my kids because we bought all our equipment last century. I pity anyone who tries to start this sport from scratch in 2025. One of those fancy British fiberglass kayaks costs $6,000. Top-end drysuit: $2,400. Carbon fiber paddle: $580. Rescue PFD: $300. That’s $10,000 in equipment costs just to begin. Don’t have the equipment or the skills to go alone? The same trip guided was $28,000 for a family of four.

I look around at prices these days and wonder if my favorite pastime has become an unaffordable luxury.

Another option used to be to send your kids to camp. Not at today’s prices! The hefty sum I once paid to send my daughter to a rustic sleepover camp for a month seems cheap now. This year the same session costs $7,000, after tax. I couldn’t even hope to earn that much while she was away. You’d never guess from the lineup of luxury SUVs on drop-off day that the whole experience boils down to a month living in a screened-in shack with no hydro or internet, swimming, singing songs and paddling.

My wife and I chose this camp because it was cheaper than the ones we used to go to. Her former camp still offers the 36-day backcountry rite of passage she fondly remembers from 30 years ago, except its cost has quadrupled to $21,645. My kids are SOL because we didn’t become hedge fund managers.

Maybe I’ve just reached the stage in life where I compare the price of everything to some bygone era when you could buy a candy bar for a nickel. But what’s happening in paddling reflects a larger trend squeezing people everywhere. Something, somewhere, is conspiring to jack up the prices of ordinary things. The promise of a nation, a wistful recent election speech said, is “hard work gets you a great life, with a beautiful house, on a safe street, under a proud flag.” And, one might add, enough money to go kayaking and to send your kids to summer camp. Yet the covenant is broken. These lives we feel are our birthright are suddenly out of reach for many, and it’s getting people riled up and placing blame.

Inflation is part of the cause, to be sure—now, add tariffs. Plus, undoubtedly, insurance. You can’t run a business these days without worrying about getting sued. A mountain guide friend complained a U.S. liability policy could cost him $50,000. It’s no different in the paddling world. Why else would camps cost so much when the kids sleep outdoors and paddle beat-up aluminum canoes?

My kids are SOL because we didn’t become hedge fund managers.

Another cost driver is how hyper-specialized and high-tech outdoor sports have become. When I first started paddling, outdoor gear was made from simple materials like metal and wood. There were no Gore-Tex drysuits. Now it’s carbon fiber everything, and there’s a different bike, ski, kayak, canoe, outfit and paddle for every specific occasion and condition. Take mountain biking, something I’ve wanted to get into but find totally inaccessible because the bikes cost $10,000, and YouTube keeps feeding me videos of riders doing backflips. The barrier to entry has become unattainable.

Like the SUV I want to buy but can’t afford to insure because it’s too likely to be stolen, I suspect these creeping costs are a sign we’re trying to prop up a recreational lifestyle that has become too rarefied and unsustainable and the bill is coming due.

We can’t fix all the root causes. But there is an easy solution: go back to the grassroots. Somewhere near you, there are regular people with regular jobs finding ways to keep doing the sport they love and making it accessible to others.

This year I joined my hometown paddling club, an organization I’d largely ignored until now, thinking I had to be completely self-sufficient with my suburban garage full of boats for every esoteric branch of the sport piquing my interest.

There’s a beautiful old boathouse by the harbor, full of watercraft and PFDs and paddles for everyone to share. Members volunteer to run events. Kids and adults ride there on bikes. You can paddle from spring through fall for only a few hundred bucks.

“You know, kayaking is a blue-collar sport,” one member pointed out to me the other day, who had been racing kayaks for 50 years. “Wealthy families go to their cottages for the summer. The kids who stay in town come to the club and become the best paddlers.”

I realized he wasn’t talking about summer camps and wilderness trips, fancy equipment and certification badges. He was talking about paddling. The elementally pure act of propelling yourself across water with a blade and human power—plus all the community that grows around the love of it, joining together to make it more affordable and accessible.

Paddling doesn’t need to be any more complicated or expensive than that.

Tim Shuff is a former editor of Adventure Kayak magazine.

No barrier to entry. | Feature photo: Kurt Gardner Photography

This article was published in Issue 74 of Paddling Magazine.

This article was published in Issue 74 of Paddling Magazine.

I agree and disagree. This is definitely a costly sport to participate in. If you buy into the hype and insist that on having those high-end toys to participate, yes, this sport is stupid expensive. However, if you can differentiate between what you need to participate versus what marketing tells you you need, it’s not outrageously expensive.

But yeah, the cost can get up there.

It is difficult to feel sorry for those who choose trips that cost that much. There are plenty of great places to paddle that cost a small fraction of that much.