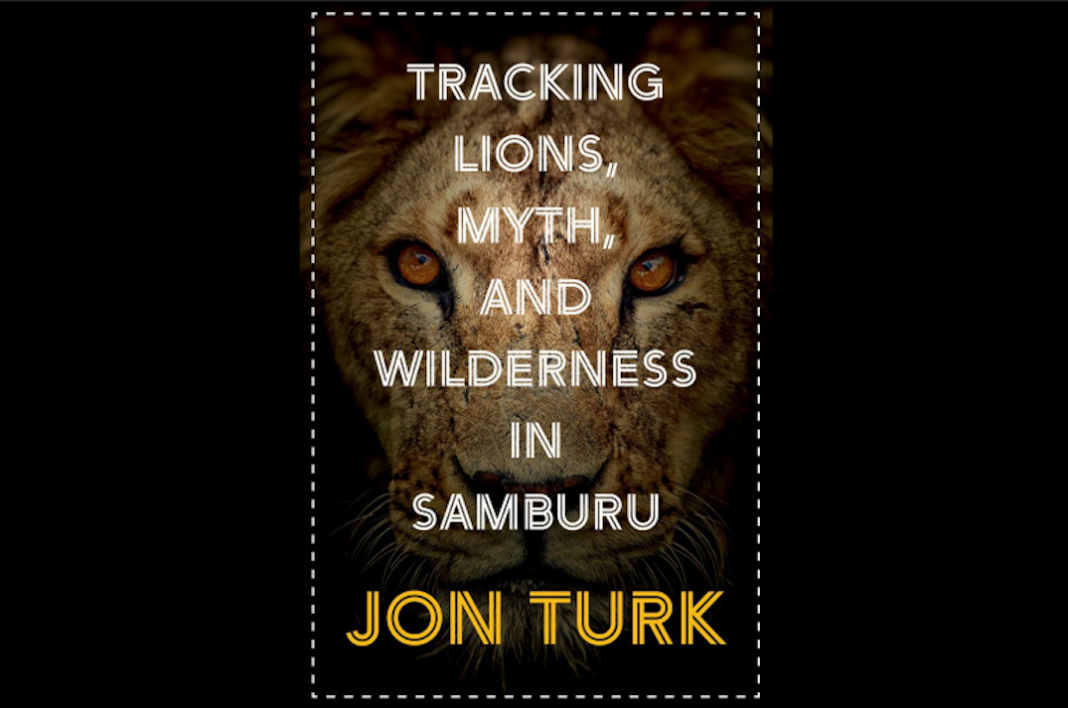

Known for his circumnavigation of Ellesmere Island, his North Pacific crossing from Japan to Alaska, and kayaking around Cape Horn, author and adventurer Jon Turk takes readers to the parched savannah and deep into human history and mythology in his new—and allegedly last—book, Tracking Lions, Myth and Wilderness in Samburu. In his signature storytelling style, Turk wraps philosophy, science and adventure into a mind-expanding read.

While tracking a lion with a Samburu headman and then, later, eluding human assailants who may be tracking him, Turk experiences people at their best and worst. As the tracker and the tracked, he investigates how the stories we tell each other can be molded into innovation, love and co-operation—or harnessed to launch armies. In Tracking Lions, Myth, and Wilderness in Samburu, Turk explores the wisdom that endowed our Stone Age ancestors to survive and how myth, art and ceremony have often been hijacked and distorted. And though there is no paddling in this tale, it’s ultimately a story about our relationship with wild places on this planet, Turk says.

Below, Turk shares how a lion-tracking expedition in Kenya turned into the book he’s been waiting 50 years to write. Pick up a copy of Tracking Lions, Myth, and Wilderness in Samburu at your local independent book retailer, or order on Amazon online.

Paddling Magazine: How did this expedition come about?

Jon Turk: I’m a believer that unusual travel suggestions are dancing lessons from God. I was giving a talk at the Harvard Travellers Club in Cambridge, and after the talk, a woman came up to me and said, I need somebody to work on a lion tracking mission. She could have easily hired a graduate student or young person—somebody schooled in the techniques of wildlife biology, which I’m not—but she asked me to come, and I said, yes.

PM: It sounds like you got more than you bargained for when you arrived. Tell us what happened next.

JT: On day three of my visit, a lion ate one of the local cows. I went out with the local headman depot to track this lion. On my way out of camp, somebody hands me a wooden club. It’s a beautiful stone age implement, and I realize this is my weapon. The tracker has no gun, no machete, no nothing. What we have to face the lion is this club. And off we go.

So, we’re walking, we’re following the tracks, and we’re fairly close to the lion. And my first reaction is I’m really angry that I’m put in such great risk when we have no defense. If this lion comes whipping out of the bushes with intent, we’re dead. And then I realize I’m getting a paleo-survival lesson here. I’m vulnerable. I have Stone Age tools and weaponry. There are two of us. How do you survive?

I had brought one book with me on this journey, Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari. And he talks about what skills people used to survive in the Stone Age. And it was our collective community, tribalism, storytelling, mythology, and art that gave us the power to survive. And you feel that very much when you’re walking through the savannah, tracking a lion armed only with a stick. I started to view my whole stay in Samburu not as a Western scientific journey into tracking lions, but as a paleo journey into understanding where power comes from. It’s an extension of my five years in Siberia with Moolynaut, a shaman who I’ve written about in several books.

And then we have an about-face. Due to all kinds of political mumbo jumbo, all of a sudden it’s become dangerous. One of the guys in the village gets shot and there’s been a massacre in a neighboring village. There’s some bad trouble going on.

Through a combination of Harari’s book and other research, I come to see the turning point where our strengths become our weaknesses, where our storytelling and mythology—that once was our survival—has been hijacked by evil people to convince us to kill one another. And seeing that dichotomy, that Yin and Yang, the wonder, the magic, the power and the evil is what the book is about.

PM: What drove you to tell this story now?

JT: I’ve been an environmental writer for 50 years, half a century. I wrote my first environmental science textbook in 1971. There are three levels of dealing with environmental problems. One is the technical level: if we use too much gas, we can get a hybrid or an electric car, something which uses less gas. The other is the social aspects. For example, if you’re driving to work, you can carpool, and by making social changes, you can reduce your fuel consumption. And when I wrote my first environmental science book in 1971, I was allowed to talk about technological problems and social solutions.

But I felt at the time there was a third level, a spiritual level, I wasn’t allowed to talk about. And for 50 years, almost 40 books, I’ve written science books and my trade books and innumerable magazine articles. I’ve not been allowed to talk about the spiritual solutions to our environmental problem. Humanity is in such a fix right now that the surface solutions are not enough. So, this book has been lingering in my mind for literally 50 years. And now I’m 75; this is my last go at it.

PM: You write: “Why do people continue to destroy ecosystems when the evidence is uncontroversial that humans are living in an unsustainable manner on a finite planet? Why do nations continue to go to war? … Perhaps I’m a fool to tackle these questions on this my last major writing project but fool or not, here I am at the keyboard.” What answers do you arrive at?

JT: We are storytelling people, and we are enraptured by the stories told to us. Stories have brought us together as a tribe and helped us survive against lions while carrying only stone clubs. And the stories unified us and made us a cooperative species. So that the sum was greater than the parts. People in the Stone Age could not survive without the tribe. Stories brought the tribe together. Now we get all these stories, but it’s turned around 180 degrees.

The stories which gave us power are now the stories killing us. The stories are we need this, we need that, or this person is selling such-and-such, and we need to buy it. Someone tells us that we have to fill our bucketlists and get on a plane and fly to Nepal to have a good time rather than going for a walk in the backyard and watching the leaves fall.

You read in the paper every day about ecological devastation, but the stories still overcome us. If I buy such-and-such a thing, then I’ll have more friends. Or, all the good-looking girls or good-looking boys will like me because I’m drinking a Pepsi cola. When you reduce it down to that, it sounds pretty silly. But we all do it.

We have to understand, at an intellectual level, how we’re being manipulated and reject the manipulation. It’s important to understand our weakness, our foible, and how it came to be through evolution—how this great strength becomes our great weakness. And, once we understand how we’ve been duped, then we can see it and reject it.

The solution is to live in the now. I didn’t make this up. This has been around for a while. There are many paths towards finding presence and finding contentment in the now. There are a lot of ways to free ourselves. But I have spent my life in nature. And if there’s one overpowering message in this book, it’s that the more time we spend in nature, the more time we’re drawn into the now, the less powerful these outside stories become. And the closer we can take this journey to what we call this consciousness revolution or this spiritual journey into a way of saving the planet.

Our Stone Age ancestors found power to survive through wonder, art, cooperation, storytelling, ceremony and love—not tools and armaments—but these ideas have been hijacked and distorted with this modern consumer-oriented, oil-soaked world. We can find our way back through nature’s healing.

I do believe that there is a path back. Nature isn’t the only way. But from my experience, it’s the most effective way to draw out of this screen time, all the ads, all the politics, everything falls away from you, out of you. It’s just a cathartic clean-out.

At 75, with so many exceptional expeditions to your name, what does adventure mean to you nowadays?

At the end of the Ellesmere expedition, Erik Boomer and I completed the circumnavigation of Ellesmere in 104 days. And we were waiting for a flight out and my body shut down, and I almost died. That had a profound effect on me. In the hospital, when I’m lying there, I think, “Okay, Jon, what did you do? Well, you pushed it as far as you can push it, you’re done.”

75 is not 25. That’s a fact. So, you have to decide whether you’re going to be bummed out, or whether you’re not going to be bummed out. And I’d rather not be bummed out.

Last winter, my body was telling me I can’t go to Nepal and do a winter ascent of Annapurna and the pandemic situation was telling me I can’t go to Fernie, British Columbia, and go skiing with my friends. So, my wife and I packed up our van and we spent the winter living out in very remote sections of the Southwest desert, just kind of hanging out, staying safe from COVID, riding our mountain bikes, hiking, and hanging out in the desert.

And it was low-key in the sense that I’m not going to write any articles for Mountain Bike News and I’m not going to win any expedition of the year awards. But it was deeply, deeply joyful.

Just my wife and myself, alone in the desert for months. We spent six and a half months out there. My love of being outside has not diminished one nano-whatever—it’s 100 percent. But you change what you’re doing. And you see the beauty and the love in what you’re doing. I mean, it sounds a little corny, but that’s just the way it is.

Pick up a copy of Tracking Lions, Myth, and Wilderness in Samburu at your local independent book retailer, or order online at Rocky Mountain Books or online at Amazon. Find a listing of Turk’s upcoming presentations here.