Eight of us stood on the beach at the banks of the Thelon River and watched the floatplane buzz over us. I smiled, knowing our pilots were choosing to give us a dramatic flyover for one more rush of excitement.

Gradually, the roar of the engines got farther away and the plane got smaller until it disappeared below the horizon. Then there we were, all spaced apart and silent, standing in that moment as a group of more-or-less strangers on a white, sandy outcrop at the edge of stilling waters.

I’d agreed to go on this trip without ever setting foot in a canoe. I had some experience kayaking on lakes in the Okanagan, but I knew that was hardly going to be a good comparison for a two-week trip down a tundra river.

Before now, I’d never seen the Northwest Territories’ famously beautiful Barrenlands. I knew nothing about this northern river. But when Jackpine Paddle asked me to join a canoe trip on the Upper Thelon River and document my experience, I knew I couldn’t say no to the once in a lifetime opportunity.

Through the Barrenlands: 14 days on the Upper Thelon River

Before the trip, I hadn’t read Alex Hall’s Discovering Eden: A Lifetime of Paddling Arctic Rivers. Our trip would follow one of the many routes he paddled during his three decades guiding, and his invaluable notes were passed down to Jackpine to build the foundation of our trip.

The Thelon River flows through a soft sandstone belt on the Canadian Shield. Fed by large tundra lakes, it forms a smooth and evenly graded course through the soft rock. Despite its remoteness, the Thelon is one of the easiest tundra rivers to paddle, with a steady current, few rapids and no portages.

On travel days, we aimed to be on the water by 10:30 a.m., paddle until we took a break for lunch, and be off of the water around 3 p.m. We had 14 days to travel roughly 200 kilometers. It was a time frame with a wide margin of wiggle room for layover days in case we came across places we wanted to stay longer, needed rest or experienced bad weather.

The cast of characters comes together

Coming as a pair on this trip were Stuart and Ken, old canoeing buddies from Saskatchewan. Stuart said a trip on the Thelon had been something he’d dreamed of for a long time. Ken could contribute to any conversation or crossword prompt on topics from Broadway to geology.

Kim lived in Yellowknife, but had lived all around the world before the Northwest Territories. She enjoyed trips like these because sometimes Yellowknife was too noisy for her. Kim hit the ground running on day one, and was the first person to attempt a swim in the water.

Louise had come from Vancouver Island but her family previously lived in Aklavik. This was her first paddling trip as well, but she was far from fearful and had no shortage of stories to tell, from swimming after a runaway boat to motorcycling across the country with her newborn.

Sharing my canoe was Keith, a videographer who lived in Yellowknife. We worked together to race ahead of the other canoes and then drift while he got footage of the other canoes passing by. Together we made up what we referred to as The Media Boat. Last summer, Keith spent three months canoeing across the Northwest Territories with his family.

Our guides were Wendy and Colin. Each day, they started work the earliest and ended the latest. What really came across was their unadulterated anticipation for paddling such a renowned river. Even as professionals, the Upper Thelon was a crown jewel and just as alluring to them as it was to the rest of us.

Building our canoes was our first group exercise. There were some initially skeptical remarks about sturdiness, but the effort that went into constructing them was proof they would be solid structures. Expertise and personalities were coming through and we thankfully bonded over the hard work and collective purpose—a good sign for things to come.

On an after dinner hike, I found Kim standing at the edge of the water. She had spotted small dark shapes on the ridge of a distant hill. From so far away, any features were impossible to discern, and the only indication they were more than rocks or shadows was when the distances between them changed. The rocks and shadows were a herd of musk oxen.

Each time they disappeared behind one hill, they returned closer on the next. Smaller musk ox calves moved quickly between the meandering adults. Most of them moved along the middle of the slopes, while one or two walked the ridge keeping an eye out over the flat Barrens around them.

Life in the Barrenlands is slow, and reminding me to slow down was the first gift it gave me. Eventually, the musk oxen were close enough I thought my presence might disturb them or they might block my path back to camp. I walked back, slower now, like them.

Adapting to life in the Barrenlands

Our first morning, getting everything packed and ready took some consideration. We let our guides play Tetris with our barrels and packs to fit them into the four canoes—our entire lives for the 200-kilometer journey.

The group paddled close together, and the most experienced canoeists were quick to provide tips and techniques, mainly to my benefit with my cumulative four hours of practice the day before.

Canoeing, I quickly learned, is a meditative form of travel—the soft rhythm of the strokes feels like a deep and slow breath gliding you forward into clear northern air. The feeling of physical exertion melted away as my body found strength in places I didn’t realize I had—all across my shoulders, back and core.

We stopped before lunch to hike along an ancient caribou fence. Along the top ridge of a long, thin peninsula, small piles of rocks had been stacked at various intervals. A caribou fence would have been used to corral and redirect caribou into an advantageous spot for them to be hunted.

Along the remains of the fence, we found plenty of quartz shards—not tools themselves, just the chipped remnants of the tool-making process. On the Thelon there were many times I felt immersed in an unchanging world of the past, preserved as if everything had happened just a few days before I traveled through it. Close enough to feel the weight and significance, but distant enough I could only observe and reflect.

In the encroaching distance, following where we had been just hours before, we could see dark clouds and a wall of rain rolling in. Everyone hurried to build the communal Hilleberg tent, a canopy large enough to shelter us all as the storm system passed. While this was our first time setting up the Hilleberg in a hurry, it wasn’t the last.

That evening, we started what would become a tradition on the trip, gathering together in the Hilleberg to work on a daily crossword puzzle. With people from so many walks of life, it was intriguing to see where our expertises lay and rewarding to test our minds after a long day for our bodies.

For the rest of the day, I hiked the hill we were camped against, although the word hill does a disservice to how prominently it stood on the landscape.

Based on topographical map data, it rose to only a mere 50 meters tall. The top was a wide, flat surface. From the top, you could see an uninterrupted 360-degree view of the horizon of the Barrenlands stretching for kilometers in all directions.

The wind that had carried the storm quickly onto us and beyond was powerful at the peak. With few trees to slow it or indicate the intensity, the deafening sound was in stark contrast to the still and unaffected landscape, peaceful and glorious while sun and shade moved across it.

Really, truly, away from it all

The next day, we traveled 22 kilometers on a strong current under sunny skies. Here, the Thelon narrowed and turned north to where Alex Hall had noted the “largest esker in the Barrenlands.”

The water’s edge gradually transitioned into 200 meters of low sandy dunes and shallow pools, with the colossal esker’s side rising above and reedy space in between. We stopped there for lunch and hiked our way toward the esker. It was about to be our first experience with how vast the scale of things is in the Barrenlands.

Created by the flow of rivers under ancient glaciers, eskers are remarkable in a grand sense, but also in their smallest elements. Embedded in the stark white sand are millions of rocks, most barely the size of a fist.

“The upper and middle parts of the Thelon River are more distant from human settlements and roads than any other location on our continent,” wrote Alex Hall.

By the halfway point on the trip, the outside world had completely faded from concern. Our daily routine had become second nature. Each day we tackled waking up, taking down camp, paddling out, snacking when we were hungry, and setting up camp again in the afternoon to rest or read or take hikes and see the beauty of wherever we had landed. I felt comfortable hiking out much farther from camp than I had in earlier days.

Our eighth day started cloudy and a little cold. Late August is autumn in the Barrenlands and while that provides relative darkness through the night and keeps some of the bug population in check, the land and weather are beginning their transition into winter. The next three days were forecasted to be the coldest on the trip, with one night dipping to zero degrees Celsius.

The water levels on the river were higher than normal. This meant features on the river were different than those in Jackpine’s notes. But this far, the Thelon had been manageable even for a complete novice like me.

With little ambient noise in the Barrenlands, even the smallest sounds can be heard from quite far. Many times I heard the sound of water churning over rocks and anticipated seeing a small waterfall spilling over the banks, only to find barely a creek tumbling forward to join the river. The approaching rapids were notably louder. The sound grew as we watched the Thelon in front of us wind between rising cliffs.

The second set of rapids had clearly changed since they had been recorded on the map. We pulled to the side, but didn’t bother scouting them the same way we did the previous set. The path through the middle was wide and clear. While the cliff sides had made the first set appear daunting, these rapids were flanked by familiar rising banks. My success with the first and second sets left me confident as we moved on to the third.

Into the river, out of the rain

We rafted the canoes together and discussed the map data we had on the final set of rapids. Colin and Louise would go first, followed by Stu and Ken, then Kim and Wendy, with Keith and I going last.

I watched Colin and Louise head through on the center-left, before dramatically indicating we needed to go right. From behind me, I heard Keith say, “Oh no, they’re going in…” Sure enough, the back of the lead canoe rose, pivoted and capsized along the right side.

There were three sections of this rapid, covering roughly 500 meters on the river with a large span between the second and third ledge. If we could navigate the first two sections successfully ourselves, that gap would be the first place we could attempt to get to Colin and Louise. The two canoes ahead of us moved to provide support.

“Stuart and Ken just went in too,” shouted Keith.

We eventually got all four of them to the side. We were off the water, but the nature of the rapids and rescue meant people were in the chilly tundra water for much too long. They needed to change and get warm.

Everyone who was able to immediately started setting up the Hilleberg and getting a fire going. We got the four shocked paddlers up the hill, sheltered and drinking warm soup to recover. The adrenaline was wearing off and the cold and wet was setting in. This was camp for the night.

I knew all my clothes and sleeping bag were completely soaked. I’d gotten complacent sealing my drybag and water had easily made its way inside. I knew I was lucky to not be fighting a chill to the core, but at that moment I counted it as the only blessing. My books were ruined and I’d lost the nightly sanctuary that was a warm sleep at the end of the day.

Hauling gear up to camp, I gave Colin a forced smile. It was as much to check in with him as it was a plea for some perspective. He looked at me and said, “The Thelon won today.”

We woke on day nine to find nothing any drier than the day before. The piddling rain through the night had kept the air humid and the cold wind did little to evaporate anything beyond what dripped out of our hanging effects.

Aside from the companionship, the food was the only thing fighting off despair during this darkest part of the trip.

Food somehow always tastes better when camping. Imagine salmon with pesto and portobello mushrooms, arugula and goat cheese salad, focaccia paninis, coffee cake and oatmeal, scalloped potatoes, and Moroccan stew. We agreed we ate more luxuriously on the Thelon than any of us did with full access to a kitchen and grocery store. We finished our meals with espresso cheesecake, peach crumble, vanilla mousse with dried raspberries and Baileys, and a collection of hot drinks to keep us warm through the days and evenings.

Back in our canoes after the rain, the Barrenlands were just as beautiful as when we had last seen them under the glow of the sun and the expansive blue skies. The pools were full, the ground was lush, and the autumn colors of the mosses in their reds and greens sparkled and breathed against the white sands and blue water. We stopped for lunch on the delta where the Thelon feeds into Eyeberry Lake from the southwest before continuing again to the north. Here we found Stuart’s lost bag from three days earlier, now almost 20 kilometers downriver from where he’d swam in the rapids.

We found a beautiful spot on the east side of Eyeberry Lake to camp and take advantage of the now miraculous weather. All our clothes were immediately strewn across rocks, beaches, and makeshift clotheslines made from tent rope and tripods of balanced canoe paddles.

There were many times during the previous few days when I had felt defeated. Times I had thought I wasn’t cut out for the trip. I was too soft, too wet, too cold, too sad, too alone. It was too far, too much. There were times when I had felt afraid and times I would have quit if I could have.

Where else could I have been tested to such limits? In the face of what had been required of me, I finally understood why a trip like this was so important to everyone who had sought it out. This is what makes these trips life-changing.

I stopped taking notes. I knew I would have no difficulty remembering the sights and events and feelings that filled the last days of the trip.

Riding high across the finish line

Our last travel day was only 25 kilometers to our take-out spot. We cleared Eyeberry Lake, which was slower progress without the river’s current to carry us, and then stopped for lunch where the Thelon began again.

From a distance, we could hear the sound of rushing and churning water grow louder. Wendy and Colin made it clear we would approach every section of rapids with caution and scout well ahead.

Before the first set of rapids, we pulled into an eddy on the right side of the river. Here, the Thelon threaded between two cliffsides, snaking west and then north again, hidden from our view by the rock walls.

The path forward looked exceptionally simple. The same high water levels that had complicated the rapids earlier had now washed out these ones nearly completely. The rocks on the right were far beneath the surface and the river ahead was undisturbed.

The canoes rocked, waves rose as we rode their tops, and I called out shallow points and navigation to Keith from the bow. My body had worked for nearly two weeks to be ready for these rapids. I gave a long celebratory whoop, loud and carefree as the current carried us to join the other paddlers. Our last hurdle.

I met the party for dinner at Bullock’s, the best fish restaurant in the middle of Yellowknife’s Old Town community.

We were loud and enjoyed cold beers and hot meals none of us had to cook. We found a place on the wall to sign, as is a custom at Bullock’s.

Dinner felt like a reunion. Like familiar people meeting each other again in an unfamiliar way. We all looked mostly the same, albeit cleaned up and in fresh clothes.

In the silences between mouthfuls and memories, I realized I felt differently. I’d gotten myself ready for dinner the way I would have before, but the person looking back at me in the mirror was not the same. Only a few hours off the Thelon River, returning to the simplest of activities of normal life, I could already feel the ways the old me was not the same as who I was now.

Marcus Miller moved to the Northwest Territories in early 2020, enjoying the beautiful northern landscapes just outside Yellowknife. After falling in love with the serenity of the Barrenlands and the satisfaction of a full day of paddling, he’s confident this won’t be his last trip on the waters of the NWT.

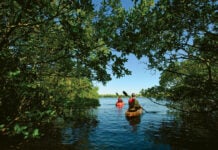

Despite its remoteness, the Thelon is one of the easiest rivers of the north to paddle. And the views are some of the best. | Feature photo: Maria Stern

This article was first published in the 2023 Paddling Trip Guide.

This article was first published in the 2023 Paddling Trip Guide.

Hello. My name is Alain Lacroix from the Ottawa area. I’m looking for information on the Thelon.

I already did the Nahanni (40 days), the Bonnet Plume (30 days) and 6 other 30 days river trip in Ontario and Québec. This summer with 3 friends, we are looking to do the complete river (30 to 40 days) I try to have a map of the Thelon were I could relye on for the rapids. Could you indicate me if this kind of map exist. And if yes, were I can get it?

Thank you for your help. Have a nice day.

Alain Lacroix, 819-271-8331, alain.lacroix566@gmail.com

We are also paddling from eyebury lake to baker lake. Any information you are willing to share would be helpful.