Go with the flow into the unknown, to see what the blue line on the map has to tell you. This is the mantra that leads former Olympic Slovenian rower Rok Rozman and fellow kayaker and friend Zan Kuncic to their dead-end predicament. They had been following a steadily growing stream of melting snow high in the remote Pindus Mountains of Greece for only a few hours, before their route widened into a lake held back by a of a wall of concrete boulders.

Unable to follow the flow any further, they sit in their river runners staring up at the man-made barrier that halts their path down the mountain valley. This is the only operating dam on the Vjosa, the only blemish on an otherwise perfectly intact river system. Aside from this, the Vjosa remains one of the last truly wild rivers in Europe.

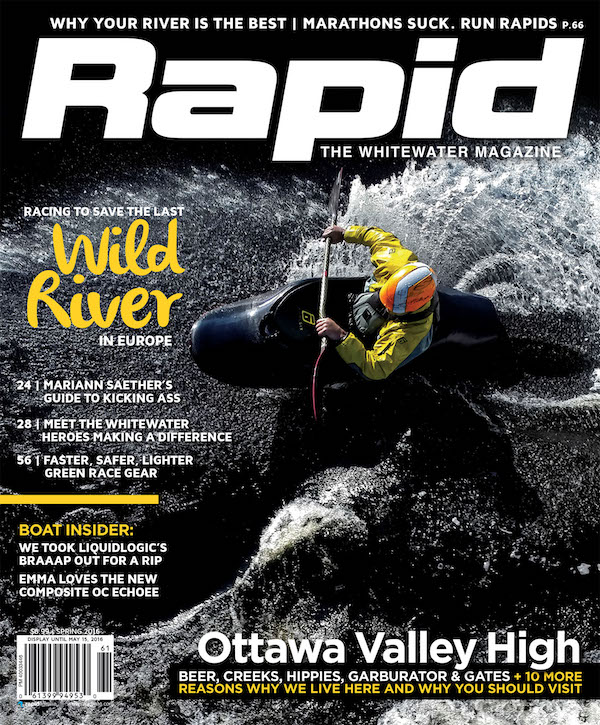

Racing to save the last wild river in Europe

The Vjosa and its many weaving tributaries, known as the Aoos in Greece where it begins, is like an ancient and deeply rooted tree, with wild and untamed branches flowing down from the Pindus Mountains towards the Adriatic Sea—but perhaps not for long. The flow of the Vjosa is slated to supply 38 hydroelectric power plants, all part of a looming dam tsunami that has already washed across Europe.

Filmmaker Anze Osterman stands on the banks to get the shot composition just right. He and Nejc Miljak plan to document Rozman and Kuncic as they paddle all 168 miles of the near pristine river in hopes of persuading the world that this one last vestige of wilderness is worth saving.

“It’s like a dinosaur. You wonder, how could it survive?”

Together calling themselves the Leeway Collective, they approached Ulrich Eichelmann, a passionate, forthright and award-winning conservationist who has been working for the protection of rivers for 26 years, fighting dam construction all over Europe. They offered to be ambassadors for the Save the Blue Heart of Europe campaign—coordinated by Eichelmann to conserve Balkan rivers—to show the world what it would miss if the Vjosa were to be squeezed into power lines.

To Eichelmann, the Vjosa is a gift to the earth, as powerful as a mountain and yet subject to human agendas. “It’s like a dinosaur,” he says. “You wonder, how could it survive?”

Water, though, is resilient by nature. The Pigai Aoos tributary dam where Rozman and Kuncic are left stranded cuts off six miles of riverbed, but then a stream forms out of the earth, joining another and gaining power and momentum with each passing bend in the river. The Vjosa is reborn.

The dam tsunami

After many long days of paddling, Rozman and Kuncic take a break in Albania to explore one of the scenic bridges that passes over the Vjosa. Their kayaks capture the attention of a few men herding sheep nearby. Rozman, a gregarious people-person, is not at all deterred by the lack of a shared language. The converation is a back-and-forth banter of wild gestures, and before they know it, they’re following one of the shepherds and his overladen donkey along the Nemercke mountain ridge to the small riverside village of Kanikol.

Inside the man’s home they are introduced to a liquid called rajika, which bears a striking resemblance to vodka. In no time the ukulele and tambourine come out, and the once quiet shepherd and his wife and brother do their best to deliver as many hymns of Albanian beauty and pride as the rajika will permit.

“There is more than one parallel when rivers and people are compared,” says Rozman. “Both are friendly and full of surprises.” As Rozman steers the conversation to the Vjosa he notices a look of solemnity and respect come across the faces of the shepherd and his family.

In Kanikol, and so many villages like it, the river is a lifeline—a living, breathing member of the community. They carry it in their bodies and minds as well as in their songs.

It’s an unfortunate predicament. Albania is also in need of the electricity that hydropower could provide.

“Most of the energy never goes to the villages,” says Eichelmann. Instead, the energy is destined for export through transmission lines, which, he says, often lose upwards of 30 percent of the electricity in the process.

“To some, river flow is just something that waits to be squeezed in a power cable so we can produce more and more and more.”

The surrounding Balkan region is slated to host over 2,700 dams, a crushing number to not only the locals, but also the nature conservationists, paddlers and anglers. Yet the Vjosa, with almost all of its tributaries intact, has managed to sustain its natural sediment flow and fish migrations.

“To some, river flow is just something that waits to be squeezed in a power cable so we can produce more and more and more,” writes Rozman in one of his journal entries used in the narration of the film. “They are the ones who don’t nourish their own gardens.”

In many ways it is Albania’s historic isolation that has preserved the Vjosa from development.

Following the Second World War, Albania’s Stalinist leader Enver Hoxha kept the country rigidly sealed-off from the rest of the world. It remained that way for four decades until his death in 1985.

With a leader who wouldn’t trust the outside world, there was no money coming into Albania to invest in dam construction. Neighboring countries began setting up dams at every bend in the river but Albania lagged behind, and suffered economically for it.

“They are still living in the fifties,” says Rozman. He says many of the villagers such as those he met in Kanikol do not even know about the bids that have been placed on the Vjosa just outside their door. As far as they are aware, the river has always flowed and will continue to do so.

The Italian job

Almost three-quarters of the way through the team’s journey, with the smell of the Adriatic Sea almost tangible in the wind, the threat of dams becomes unquestionably real. They paddle through the Kalivac site, the first of the plotted dams to enter the implementation process.

Just after paddling through a massive alluvial plain, signalling the health and positive sediment flow of the river, Rozman and Kuncic enter an area that looks more like an open mine pit than a river. Terraced pyramids are cut into the surrounding hillsides and the tree line has been flattened into submission. The sounds of owls and nightjars are replaced by the hollow echo of their reluctant conversation as they enter the abandoned worksite.

The Kalivac dam construction began in 2007 but was halted when it was only 30 percent complete amidst a flurry of controversy. Francesco Becchetti, an Italian energy and waste removal heavyweight, had intended to sell the electricity to Italy through 60 miles of transmission cables.

For Albania, a country seeking a way into the European Union, hydropower was seen as a green solution and a way out of energy insecurity—never mind the deforestation, soil erosion and biological disruption.

“But in 2009, something strange happened,” says Eichelmann. The value of electricity in Europe collapsed and in an instant Becchetti halted the project. Since then, Becchetti has been accused of fraud-related offences and money laundering for dealings related to the Kalivac project. The Deutsche Bank, the second half of the joint venture project, also pulled out.

The Kalivac is a sleeping giant and Rozman and Kuncic paddle through the abandoned construction site as if afraid of waking it. “I know that this is a David and Goliath situation, as always, and it’s not very likely that we’ll win,” says Eichelmann. “But nevertheless, until the dams are finished and the reservoirs flooded, we should not stop our fight.”

Science may save the Vjosa River

If the rest of the world is any indicator of how this struggle ends, it’s going to be an uphill battle for conservationists like Eichelmann and the Leeway Collective team.

But they have a few unlikely heroes on their side—for one, trout.

Before they left, Rozman, who is currently completing his masters in ecology and biodiversity, met with the Balkan Trout Restoration group in Slovenia and offered to collect trout samples on their journey, at no cost.

“If we find a new subspecies or something, then it’s easier to protect the river,” says Rozman. “Then you have legislation that helps you protect the river.”

Of the five tissue samples he brought back, three contained different species of trout. The results, while preliminary, indicate different evolutionary origins and a huge potential for genetic diversity.

“If high diversity of the trout population from the Aoos River is also confirmed on a larger scale, this will be a firm argument for protecting and preserving this population,” says Ales Snoj, a senior research associate at the University of Ljubljana and member of the Balkan Trout Reservation Group.

For Slovenia’s Sava River, a decision on a chain of hydroelectric power plants is currently pending, waiting for an assessment on the stability of the Danube salmon population there.

Even if every nature conservationist put the Vjosa project as their number one issue, they would still be outnumbered. For Eichelmann, the key is joining forces with the kayaking and fishing communities.

“For the Vjosa to stand a chance of surviving, all groups must work together.”

“The funny thing here is that the three groups—nature conservationists, fishermen and kayakers—normally have a bit of a rivalry. They don’t like each other very much,” Eichelmann explains. The anglers resent the conservationists and kayakers for disturbing the still waters and the conservationists resent the kayakers and anglers for disturbing nature.

But, he says, for the Vjosa to stand a chance of surviving, all three groups must work together.

Balkan redemption

Some foes and allies are less clear. Earlier this year, Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama announced his support for the idea of the proposed Vjosa National Park, the only wild river national park of its kind. He praised the idea of the park as a pride point for Albania, although his recent actions, sending out a tender for a dam upstream from Kalivac, have suggested he may have other plans for the area.

The Leeway Collective team plan to remind Rama of his spoken commitment at a Patagonia-sponsored event this spring that they’re calling the Balkan Tour. They hope to guide a mass of paddlers on rivers threatened by dam development from Slovenia across seven countries ending on the Vjosa in a massive flotilla. Along the way they will recruit paddlers and ambassadors from various watersports, as well as locals, to sign a petition that will eventually be presented to the Albanian parliament.

“Our love of and dependence on free-flowing, undeveloped rivers and wild places have inspired us to advocate against similar developments for nearly 30 years,” says Mihela Hladin, Patagonia’s European social initiatives manager.

While still in Greece, before Rozman and Kuncic came upon the Kalivac dam site, they found a narrow canyon that continued in darkness for eight kilometers. Rozman says it was filled with some of the most delicate and technical class IV whitewater you could hope for.

As they paddled single file through the deep canyon, the moans and booms of the fast-running whitewater echoed through the darkness. They could almost hear the river breathing in and out, as if in deep slumber waiting to be restored to its full glory.

Katrina Pyne is a freelance writer, photographer and videographer based in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2016 issue of Rapid. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2016 issue of Rapid. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.The Vjosa River is a gift to the earth, as powerful as a mountain and yet subject to human agendas. | Feature photo: Anze Osterman