I pile the last creeker atop an already swollen stack of boats, recklessly exceeding the recommended load for my rack. A posse of river runners who flood into Squamish every year at this time is packing the last of their gear into my truck. Across a bed of perennials, my neighbor is washing his Windstar and staring in disbelief at our macramé of boats. Two more vehicles stacked to precarious height pull into our quiet cul-de-sac.

My cell phone is ringing with stragglers looking to get in on the mission. We are heading up the Ashlu today; this is the last season that the river will be free-flowing. Paddlers from all over the world are now chomping at the bit to explore the majestic, moss-covered granite canyons of the Ashlu before it is diverted into a tunnel.

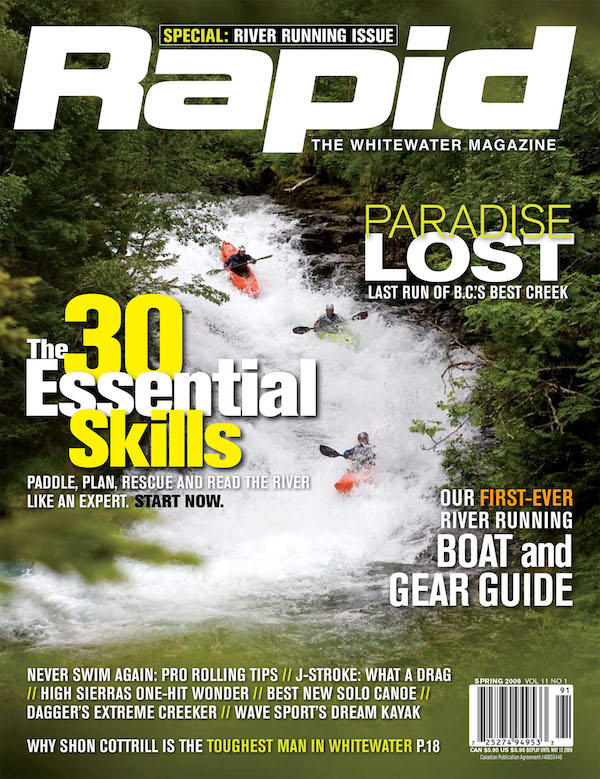

A final descent of the Ashlu River

Fifteen years ago in British Columbia, running rivers and creeks was at the very core of whitewater. Entire mountain ranges of expeditions and adventures were to be had in long pointy Dancers, Overflows and Corsicas. Sporting thick neoprene and teal Pro-Tec helmets, function far outweighed fashion for the early pioneers. The thought of giant aerial blunts at Skookumchuck had not crossed their minds. They were too busy trying to determine the magic amount of flow and gradient that would make possible successful descents easily accessible from logging roads.

In 1993, Stuart Smith launched into the upper sections of the Ashlu and returned with reports of polished granite bedrock and crystalline blue water. Four years later the next wave of local Squamish paddlers, including LJ Wilson and Sam Maltby, completed the first descent of the Ashlu’s lower reaches, now known as Box or Commitment Canyon. The river quickly became the most sought-after classic in the Sea-to-Sky Corridor. Just 30 minutes outside of Squamish, the rapids were clean and the scenery was colossal. Little did these paddlers know BC Hydro had already identified the Ashlu as one of the best candidates for what they call “run of the river” hydroelectricity generation.

Crossing into a changed landscape

It’s now the fall of 2008 as we caravan toward the Ashlu River. Driving almost due north out of Squamish we turn off the Sea to Sky Highway and slip through First Nations reserves around the town of Brakendale and cross the dam-besieged Cheakamus River. The vine maples’ giant leaves litter the narrowing road as we pass under their thick canopy beneath the lurking shadow of the Tantalus Range. The hot summer has melted most of the snow off the peaks, leaving the bluish-grey glaciers exposed and glistening in the sun.

The pavement soon turns to gravel as we hook a left off the Squamish Valley Road to head up the Ashlu drainage. The once overgrown logging road barely passable with a 4×4 is now a wide and well-traveled thoroughfare. Power poles line an immense clearing that parallels the road for several kilometers, interrupting the otherwise dense forest. I can’t help but think about how much the landscape must have changed here since the first paddlers explored this valley almost 15 years ago.

We reach the security checkpoint at the entrance to the construction zone and my vehicle license plate number is documented as is everyone’s name. The guard has the same look of disbelief that my neighbour expressed just a couple hours earlier. “Watch out for the rock trucks, park to the side of the road, be sure to report back to us when you leave, and have fun,” he says.

The checkpoint is a metaphor for the deeply divided local struggle over the Ashlu. On one side of the fence stand bitter paddlers, local residents and fishermen who fought to keep the valley wild through three years of public hearings. On the other side stands the Ledcor Group, with hundreds of personnel and pieces of heavy equipment, and the sweeping pro-industry legislation that supported the construction of this private power project.

We drive up the road, through the construction and past the tunnel site. Massive iridium lights tower overhead, sprouting on alien steel poles where an earthy grove of giant Douglas fir trees once stood. One of the mossy roadside cliffs is now scraped bare with a four-meter-wide bullet hole punched into it. This is the exit end of the tunnel, where the water of the majestic Ashlu will one day pour through power-creating turbines. Dust created by the boring machine billows out of the hole and settles in a grimy film on a 30-tonne Volvo dump truck awaiting another load of gravel. The river flows just below in a perfectly natural state, unaware of its fate.

The Ashlu is a river runner’s dream

The Mile 25 Bridge above the waterfall we call 50/50 is our immediate destination. This is where we get a good visual on flow and decide that the level looks perfect for us to link three different sections for what will amount to my favourite B.C. river run.

To run the Mine Section, through the Mini-Mine and straight into Box Canyon, we have about 10 km to cover with at least two mandatory portages. This is the first time anyone in our group has attempted to run these three sections of the Ashlu in a single day. This feat has been accomplished before, but with the hydro development underway, today’s run may be the last.

We put in on river-left just upstream of an abandoned granite mine. The derelict trucks, buildings, pipes and fuel barrels have been rusting a slow death since the late seventies. The trashy landscape reminds us how humans have scarred this beautiful valley many times before. Walking through the forest to our put-in, the thundering sound of the Ashlu drowns out the distant noises of excavation and all of the energy expended to get here feels well worth it.

On the river, I splash my face several times before tucking my skirt under my drytop and securing my helmet. Directly below is a technical Class IV rapid and immediately the group’s focus turns from environmental issues to running the river.

The Ashlu is glacial-fed late in the season. The silt deposited by the glaciers gives the water a milky, opaque color that blends almost seamlessly into the polished granite bedrock. This is a river runner’s dream with everything you could possibly want. Clean water, technical boulder gardens, runnable waterfalls, ledges, stunning scenery and enough eddies to break the run down rapid by rapid. Every section of the Ashlu is pool-and-drop. Up high the Ashlu has runs for Class III paddlers, in the middle it becomes Class IV and the lower sections challenge even the best Class V boaters.

Dropping deeper into the Mine Section our attention is consumed by the river. All the earlier sights of hydro development have been replaced with narrow horizon lines. I blink my eyes to take a picture for my neighbor and the guard. If they could only see the ferns waving high along the canyon rim, hear the power of the river squeezing through the granite canyon, smell the pitch from the Douglas firs baking in the sun or just feel the refreshing splash of the cool water they might understand our motivation to squeeze into eight feet of plastic and paddle down the river. They might understand why so many of us fought to keep the Ashlu this way.

A calm green path leads into the lip with not even a small wave or ripple in the way. Then you fall through the air…

After two hours on the river, the Mine run is easing and we approach the weir and diversion site. Once a shallow Class III boulder garden, this stretch of river has now been transformed into a composition of concrete structures designed to control the flow of the river. Soon the Ashlu will have a two-way valve, where water can either be directed through the gaping maw of the diversion tunnel or released into the canyon below. Big excavators are digging the foundation for a building to house the computer controls. We drop over the weir one by one and realize the same water we are floating on will soon be used for electricity. Once diverted into the cavernous tunnel the water will be sent thundering through the mountain, spinning three giant turbines to power up to 20,000 homes.

The Box is directly downstream. It’s entrance is guarded by a tricky 10-meter waterfall named 50/50. Every time I see the falls, I think of a trip I took down the river with Willie Kern in 2006. An icon among expedition paddlers, Kern has more than a decade of paddling experience on rivers around the world. Together with his twin brother and five other team members, Kern bagged a first descent of Tibet’s Tsangpo Gorge in 2001, widely acknowledged as one of the greatest kayaking expeditions of all time. His reputation has led to a belief held by many of his contemporaries: “If the Kern brothers won’t run it, nobody will.” That day on the Ashlu, Kern told me the waterfall should be named “10/90… 10 percent of the time you look at it and don’t run it and 90 percent of the time you walk right past it.”

We all hop out at the calm pool above. Instantly people start talking about wanting to run it. We formulate a plan and scout the line while the rest of the group portages around to the ledge below. A calm green path leads into the lip with not even a small wave or ripple in the way. Then you fall through the air becoming engulfed by the falls itself before getting spit out in the pool below. In a matter of seconds the run is over. Four of us run it and one manages to come out upright. Today we are 25/75.

Work continues to keep wild rivers flowing

Over the past few years I have surrounded myself with paddlers who enjoy running rivers. Not just people who want to go paddle whitewater, but friends who share the passion for exploring, working as a team and using kayaking to travel through the world’s most majestic places.

A sense of exploration with unpredictable aspects is ultimately what we are after. The challenge of having to pick apart the river and being rewarded for getting it right are second to the wilderness experience and camaraderie found in paddling as a team.

It is hard to stomach the loss of rivers like the Ashlu. Our battle to keep wild rivers wild parallels the plunge we took at 50/50. Up against a power company and the government in our fight to save the Ashlu, our chances of success may have been 50/50. River runners everywhere need to continue to work hard as a team to plan our lines through the myriad of proposed power projects. If we don’t, before long we may find ourselves walking them all.

Bryan Smith is a filmmaker based in Squamish, British Columbia, and a veteran of expeditions in India, Peru and North America. His award-winning films 49 Megawatts and Pacific Horizons are available through Reel Water Productions.

This article originally appeared in Rapid’s Spring 2009 issue. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.

This article originally appeared in Rapid’s Spring 2009 issue. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.

The tranquil pool of Tea Cup Eddy offers an evanescent reprieve from the Class V cataracts of Box Canyon. | Feature photo: Phil Tifo