To build your own kayak is to take part in a 4,000-year-old tradition beginning when the first Inuit hunter pieced together driftwood and sealskin and took to the Arctic sea. The process can be as simple or as complex as you like, ranging from assembling pre-cut pieces of a stitch-and-glue kit to creating a museum-quality craft of strips of cedar. We review three of the top techniques to get you started on a DIY boat-building project, plus five myths about wooden boats that don’t hold water.

3 Top Techniques to Build Your Own Kayak

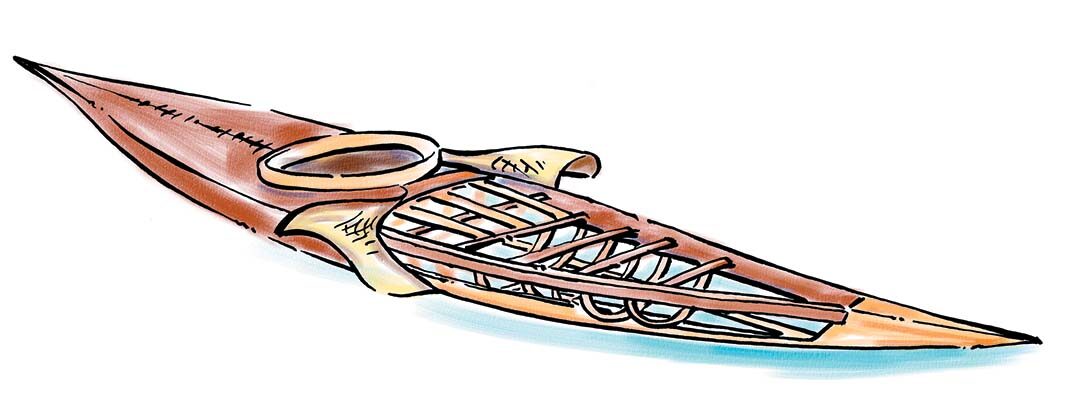

1 Skin-on-frame

For thousands of years, kayakers stretched and sewed sealskin over a skeletal frame of driftwood to create sleek, seaworthy crafts used for hunting in icy circumpolar waters. About the only thing distinguishing a modern skin-on-frame kayak from its Inuit origins is a newfangled, rot-resistant nylon skin. A lashed or pegged frame creates an edgy, hard-chined hull. A sculpted masik—the deck rib immediately ahead of the cockpit—locks the paddler in the boat. The characteristic low back deck enables unlimited options for rolling.

Challenge: Builders need basic woodworking skills and the patience to take on the finicky tasks of joining the frame with mortises and tenons and sewing the skin. But don’t be intimidated. Building involves many little steps, very few of which can cause irreparable damage should you make a mistake.

Commitment: 60–120 hours, depending on whether the DIYer cuts a few detail-oriented corners.

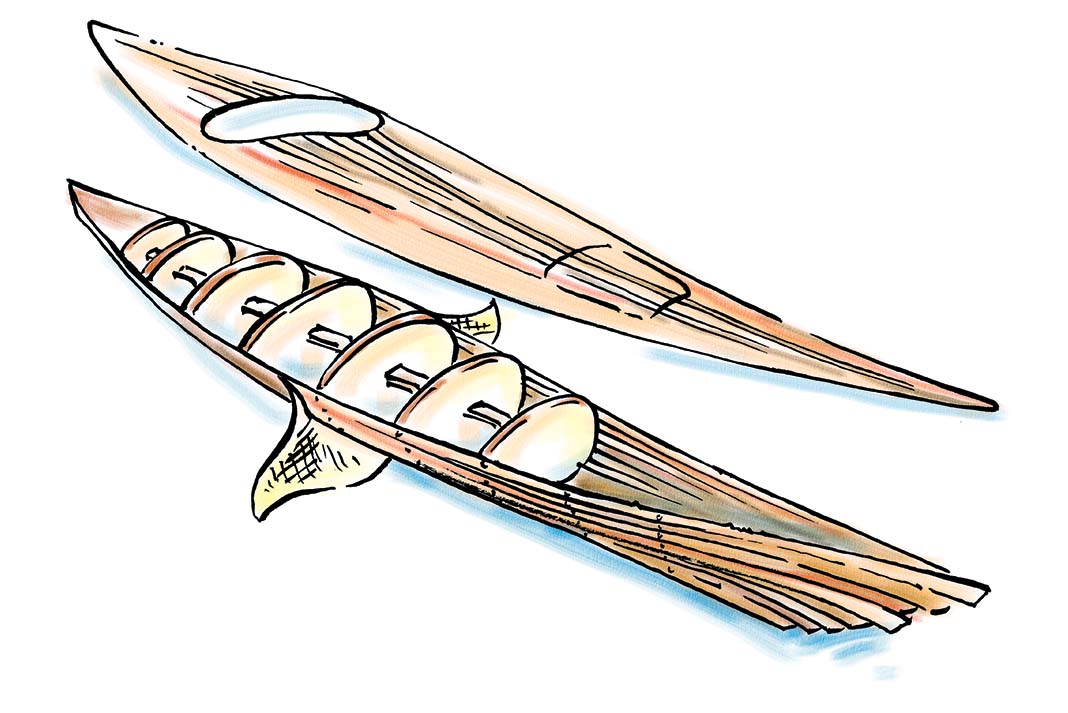

2 Woodstrip-epoxy

A well-built cedarstrip kayak has the sheen of a fine piece of furniture. It’s no wonder many builders are tempted to hang their creation on the wall and never let it touch water. Beneath the glossy surface is a brawny fiberglass-wood composite that’s surprisingly tough. The hull and deck of woodstrip-epoxy kayaks are built on a strongback—a series of plywood forms over which narrow strips of bead and cove are fastened. Once hull and deck are attached, the entire structure is covered with fiberglass and epoxy resin, and finishing details like the cockpit and hatches are installed.

Challenge: Though not quite as foolproof as stitch-and-glue, complete kits and detailed instructional manuals like Ted Moores’ book Kayakcraft make strippers a reasonable project for novice woodworkers.

Commitment: About 150 to 200 hours.

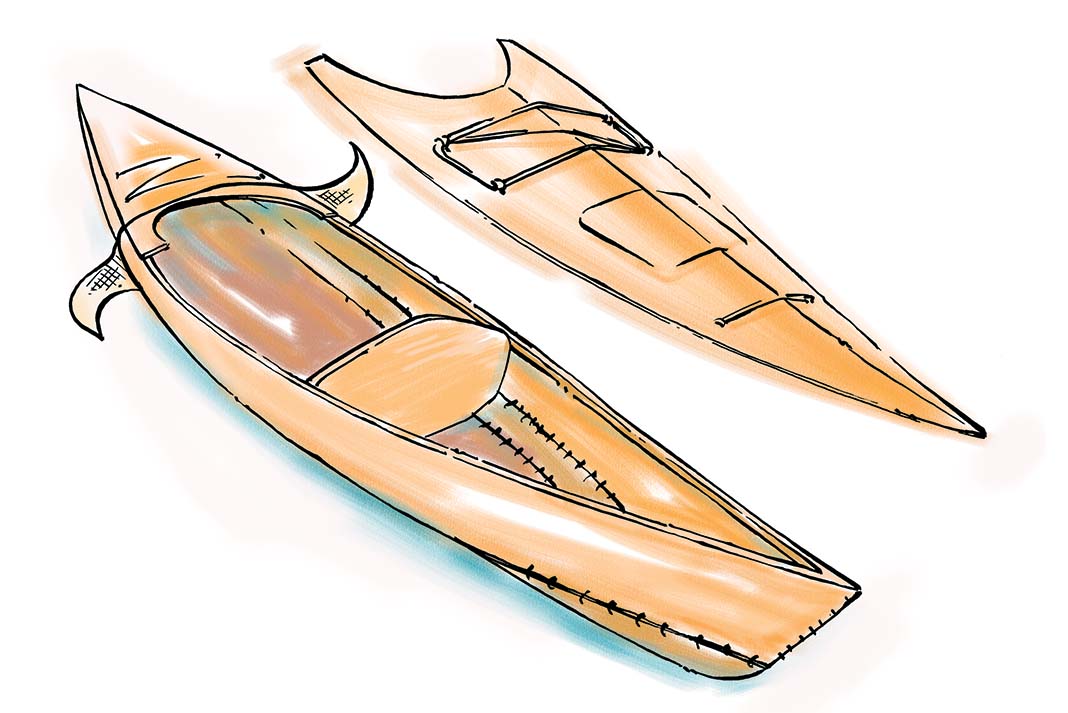

3 Stitch-and-glue

The precision-cut plywood panels of kit boats from designers like Chesapeake Light Craft, Getonthewater.ca and Pygmy Boats make stitch-and-glue the easiest technique for first-time DIYers. The panels are temporarily sewn together with wire, seams are locked into place with thickened epoxy fillets and the entire structure gets fiberglassed inside and out. Most models use temporary jigs in the stitching stage to ensure a properly aligned hull. At least two pieces of plywood go into the deck, which is then fastened to the multi-chined hull with epoxy or a gunwale-like strip of wood known as a sheer clamp. It’s also possible to combine a stitch-and-glue hull with a woodstrip-epoxy deck to create a more aesthetically pleasing hybrid eliminating the awkward process of bending plywood.

Challenge: Precision-cut plywood panels and detailed instructions make kit boats well within the reach of first-time woodworkers. It’s really just a sewing and fiberglassing job.

Commitment: The average builder can produce a stitch-and-glue kayak in 45 to 80 hours.

5 Wooden Boat Myths Busted

1 Wooden kayaks are fragile

Plywood panels and strips of cedar are just as durable and impact-resistant as store-bought composite kayaks when sandwiched between layers of fiberglass and epoxy resin and coated in UV-resistant varnish.

2 Wooden kayaks are high-maintenance

Wood-fiberglass kayaks require light sanding and a quick coat of varnish every three or four seasons—a small investment to maintain a beautiful watercraft.

3 Wooden kayaks are difficult to build

The simplest pre-cut stitch-and-glue kit boat can be built in 45 hours with minimal tools and no woodworking experience. By signing up for a boat-building workshop, reading instructional manuals and joining an Internet kayak-building forum, just about anyone can build a wooden or skin-on-frame kayak.

4 Wooden kayaks are heavy

A full-size stripper or stitch-and-glue touring kayak weighs about the same as a carbon-Kevlar boat.

5 Wooden kayaks lack performance

Wood-fiberglass construction yields ultra-stiff, efficient to paddle hull shapes; and the tight fit of Greenland-style skin-on-frame kayaks make them effortless to roll.

This article originally appeared in Paddling Magazine Issue 65. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine’s print and digital editions here, or download the Paddling Magazine app and browse the digital archives here.

To build your own kayak can be as simple or as complex as you like. | Feature photo: Adobe Stock