Ever lifted a tag on a whitewater kayak and wish you had a translator to interpret the jargon? Designer for Dagger Kayaks, Mark “Snowy” Robertson, knows his way around a boat—in production, on the water and in retail situations. He has been designing kayaks for almost 15 years and he’s keen to help you decipher the key design features of whitewater kayaks.

Here Robertson translates the top three defining design characteristics into tangible explanations to help you predict how that in-store beauty will perform on the water.

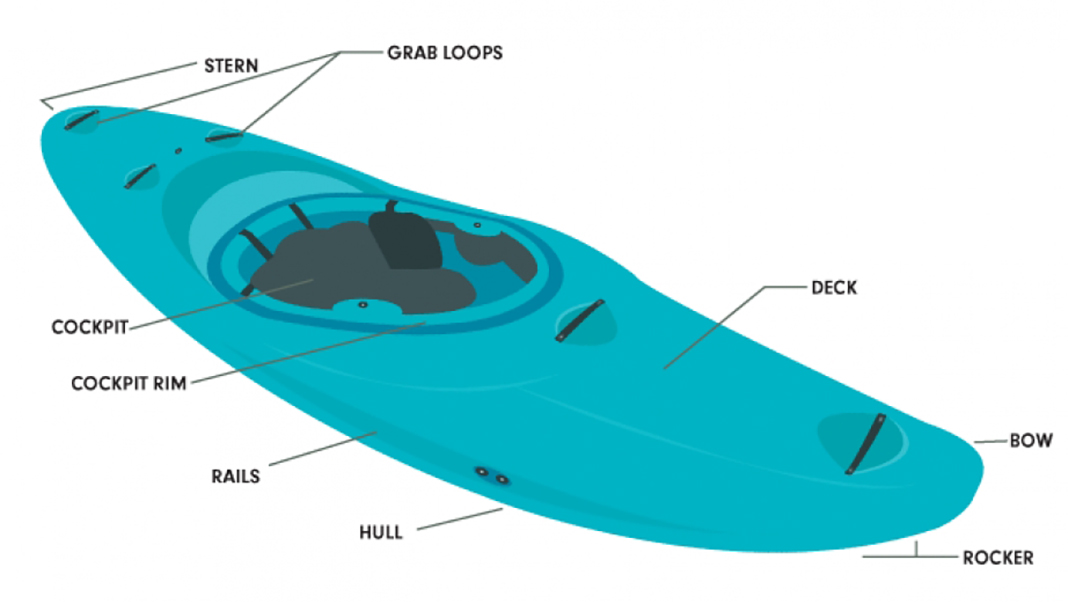

The kayak hull: decoded

“The hull of a boat is the most defining feature of a kayak, and the first you should look at,” says Robertson, because each hull shape will feel distinctly different on the water.

There are three distinct types of hulls in whitewater kayaks: planing hull, displacement hull and semi-displacement hull.

Planing hulls

Planing hulls have a flat surface on the bottom of the boat, commonly seen on playboats. The flat bottom of a planing hull will plow through the water at low speeds, but at higher speeds—such as when shooting down the face of a wave—it’ll skim on the surface and allow for spin.

Displacement hulls

Displacement hulls are rounded, like the bottom of a banana, and push the water aside as they travel through it. You’ll see this design on most creek boats. The continuous curve of a displacement hull allows the paddler to track and edge easier, but its primary stability might feel lacking in comparison to a planing hull.

Semi-displacement hulls

The semi-displacement hull, a more recent design, is a combination of the two, with a slightly flat hull transitioning into a curve. Semi-displacement hulls are a compromise of sorts, offering some of the stability of a planing hull and a portion of the tracking of a displacement hull.

The kayak rocker: decoded

Rocker is the curvature of a boat from bow to stern—just look at the side profile of your kayak. The angle and amount of rocker affects the speed and maneuverability of your kayak in whitewater.

“Continuous rocker generally has front-to-back continuous curvature,” says Robertson. “Kick rocker has a sudden and more obvious transition that you see in playboats, aimed to give more of a pop and release on a wave.”

Generally, less rocker means more boat in the water and a longer waterline, equating to better tracking and more speed. Boats with less rocker are designed for more technical paddling, like steep creeks, says Robertson.

More rocker means less plastic touching the water, which makes the kayak more maneuverable, and more capable of riding up and over river obstacles.

The kayak rails: decoded

The rail of a whitewater kayak is the point where the hull meets the sidewall and is marked by a protruding edge that runs the length of the boat. Some paddlers will use the term edge interchangeably with rail.

“To separate the terms, I would say that an edge could be used to describe a defining location or hard point within a rail,” says Robertson. “A rail can be softer and more rounded, but an edge would be a hard transition surface within that rail.”

What’s important for a prospective buyer is this: Rails give you control in the water and allow you to carve, but catching an edge can also cause you to flip—instantly. The more aggressive your rails are, the more aggressively you can carve, and the more likely you are to end up underwater if you tilt the wrong way.

This article originally appeared in the 2016 Paddling Buyer’s Guide issue.

This article originally appeared in the 2016 Paddling Buyer’s Guide issue.

Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.