More than 4,000 years ago, the earliest kayaks were constructed from driftwood and the skins of marine mammals—and if anyone has a claim to building modernized versions, it’s Kiliii Yüyan.

An American of Chinese and Nanai (Siberian Native) descent, Yüyan grew up on his grandmother’s stories of heroes riding the backs of orcas and fish bigger than canoes. But it wasn’t ancestry alone that led Yüyan to build his first skin-on-frame kayak—it was his appetite.

Since his late teens, Yüyan had been interested in the traditions of hunting and gathering. He started embarking on rewilding expeditions led by British ex-pat Lynx Vilden—a survivalist who has been teaching primitive living skills since 1991—and it was on these trips he learned just how difficult the land could be to live off.

The one exception to the rule? The ocean. He reasoned a kayak would be a stable, strong and portable platform to fish, and would give him access to otherwise inaccessible waters.

“I could have just bought a plastic kayak, but there’s more to the soul of a skin-on-frame,” says the 41-year-old. “It was part of my ancestry, but more than anything, I was driven by my desire to eat.”

That was 17 years ago. Now the owner of Seawolf Kayak, a Seattle-based boat building business, Yüyan has constructed more than 600 kayaks. Every year, alongside instructor Addie Asbridge, he teaches dozens how to build their own skin-on-frame kayaks at nine-day workshops in America, Europe and the United Kingdom.

“The building of a boat brings together so many disparate aspects of being close to the land. From gathering the wood to knowing where it comes from, every step is like retracing steps your ancestors have taken: They’ve done the exact same motion before,” he says.

His early designs, he concedes, were “terrible” in comparison to Seawolf Kayak’s current product line-up. Its five models range from the Kelpie, an ultra-narrow “Seabiscuit of kayaks,” to the stable Selkie, designed for multi-day trips. Constructed from cedar frames, bamboo ribs and ballistic nylon, most weigh-in at just 26 pounds. Despite their lineage, his boats aren’t intended to be replicas of those found in Greenland or the Aleutian Islands. Their users are interested in camping and playing in the ocean, not harpooning seals.

It’s arguably his primary passion—photojournalism—that has allowed Yüyan to explore his northern roots fully. An award-winning photographer who specializes in the Arctic regions and Indigenous issues, Yüyan’s images have appeared in Vogue, TIME and Bloomberg Businessweek.

One 2014 trip to northern Alaska to learn the art of skin-sewing (a process involving stitching seal skins together so they become fully waterproof) from Iñupiat elders resulted in a multi-year photography project. Over the course of three years in Utqiagvik, Yüyan documented the community’s subsistence whaling culture. The resulting photos were published in National Geographic and shown at the British Museum.

More than success, the project gave him a sense of belonging. “I found the thing I was looking for in so many ways; I feel at home there,” he says.

Yet, while northern and Indigenous communities are the common thread in his work, Yüyan has yet to return to his ancestral homeland. He’s been held back by Russia’s notoriously difficult visa processes and a harsh truth: The place mythologized through his grandmother’s stories no longer exists. It’s long been destroyed by decades of colonialism and communism.

Instead, Yüyan is currently starting to work on a skin-on-frame kayak from the Nain culture. It, too, is a project with complications; no drawings of the boats exist and only one modernized model remains in a museum in Khabarovsk, Russia. But like reconnecting with his Indigenous identity, Yüyan is in no hurry. After all, he says, boat building is about evolution, not revolution.

“It will be nice to take my time with it and figure out how it’s going to work,” he says.

This article was first published in Paddling Magazine Issue 62. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine’s print and digital editions here, or browse the archives here.

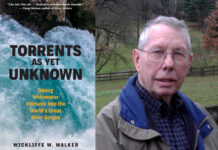

Kiliii Yüyan’s Seawolf Kayak designs aren’t replicas. Instead, he says they’re designed for what modern kayakers do—playing in rough water, photographing wildlife, camping overnight, paddling for weeks and fishing the ocean. Photo: Courtesy Filson // Photography by Ford Yates