Filmmaker and world-class kayaker Steve Fisher gave a TED talk this Saturday in Athens, Greece, where he discussed the question, “how do you prepare for something that’s never been done before?”

In keeping with TED.com’s mission, “Ideas worth spreading,” the theme of TEDxAthens was “Uncharted Waters” and who better to speak on the subject than Fisher, a Redbull athlete and National Geographic Adventurer of the Year who’s led teams of kayakers through some of the world’s biggest whitewater.

Fisher talked about his tactics for taking on monstrous rivers and his approach to managing risk in deadly whitewater.

“We can mitigate risks purely by understanding them. And the way that we understand them is we take a seemingly impossible idea and we break it down into digestible parts and we look at each step individually and see if that is attainable.

What happens then is that we find that many of our fears are unjustified, and very often we find that what’s before us is far less risky than we thought.”

Fisher explained that kayaking, like other extreme sports, isn’t about being a death-defying daredevil, but practicing enough to develop the skills to make good decisions about when to push the limits and when to realize the risks are too high.

“As humans we are not inherently risk-adverse. We evolved by taking risks, so it’s ok if there are risks in what we do. We simply need to understand those risks, and once we understand them, we’re ready to take the first step.

“If I look at the whole rapid it’s far too daunting. So what I need to do is break it down into smaller chunks, into individual moves, and see that I can do each move individually. Only then do I figure out how to link those moves together.

“What we’re trying to do is establish the path, or line, that we’re likely to be on and the reason we’re doing that is to eliminate the parts of the rapid that don’t affect us, the parts of the rapid where we will not be. If we do that we can look and see if there are any deadly features; if those deadly features are in the eliminated part, we never have to think about them again. And if those deadly features are in our path and they’re unavoidable, well then we don’t go. It’s far too risky. That’s how extreme sports works—sorry to disappoint you.”

Fisher told the audience that there’s no shame in turning around and saying no when risks are too high, a lesson he applies to life in general, as well as his kayaking career.

“In kayaking, there’s no turning back, so what that teaches us is not to panic when things go wrong. When the unexpected occurs we have no choice but to solve the problem and keep on moving. But fortunately, as in life, if we zoom back just a little bit, perhaps to where we haven’t yet climbed in the kayak and made the commitment, we get to see that very often we can start down a path, realize we’re on the wrong path, turn back and reset the plan.”

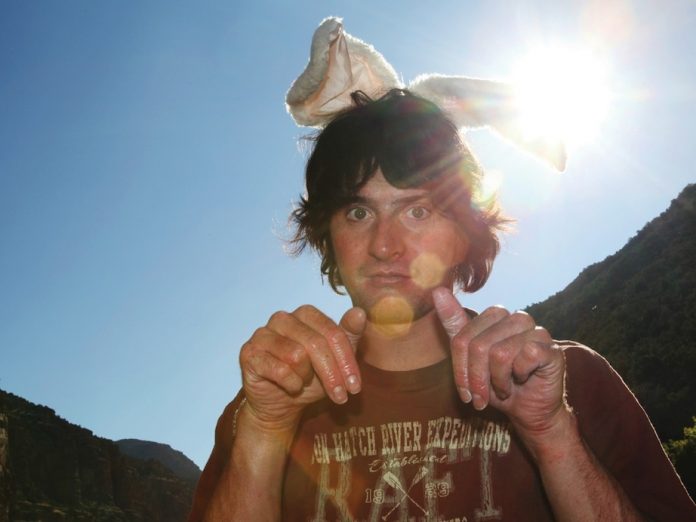

He gave the example of a trip to Victoria Falls, pictured on his slide in the above photo, when he and his team decided their mission was too dangerous.

“We gave up, but we didn’t have to feel ashamed of it. If you refuse to give up on an idea, then you inhibit your ability to experiment. But if you’re willing to give up after a good effort, then when you do give up there’s no reason to feel guilty.”

For the full video version of Steve Fisher’s TED talk, click here.