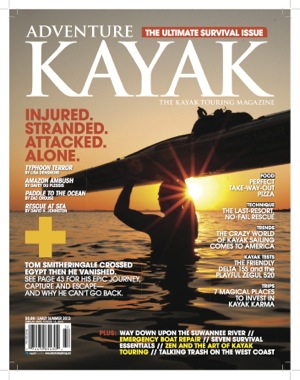

Long trips, short trips, any trips out on the water are money in the Bank of the Soul. We can catch a sunset paddle, make a full day of it or head off on a weekend outing, sleeping on the beach and enjoying a mini adventure. These short trips are typically experienced with a high level of stimulation. Odds are we’ll pack a cell phone along, not only for emergencies, but to say hi to significant others from the evening campfire.

We live in a high stimulation culture and our recreation is an expression of that. We are encouraged to get out and do stuff, hit it hard and make it happen. And I’d be the last person to knock the approach. Every sporting passion I’ve ever had was pursued like a flaming comet. But there is another kind of trip—the long trip—and it is a different breed all together.

About a decade ago, three friends and I attempted to start an adventure school based in Washington’s San Juan Islands. One of the tenets reflected in our mission statement was the importance of getting our kids out into the wilderness long enough for them to actually arrive—three weeks minimum. Between the mindset of preparing to depart and the mindset of locking onto home near the end, there is a narrow window of time when a person feels as if she is fully present “out there.”

Like the 30 seconds we’re supposed to wait after hitting the reset button on a modem so things can default to their natural configuration, a long trip into the wild provides a similar defaulting. A chance to unplug, settle in and get into rhythm with the primacy of the natural world.

When it first became obvious to me that I needed a long pilgrimage trip, I planned it out well ahead of time. Then I spent months alone exploring the coast at my own pace, settling down on a beach when I felt like it, or by a river where the salmon were running, or stuck in a pea gravel cove when a storm rolled through. Like Robinson Crusoe, I focused on the necessities of thriving on a remote seashore where the chop wood, carry water Zen principle dominated all. I found myself feeling as free and present as I could remember ever having been; the caliber of it was child-like.

On the water, I dropped right into the paddling archetype of one man traveling the coast in a small boat. The repetitive rhythm of dip and pull, the rise and fall of the boat and knifing of the bow soothed my soul. The busy planning, worrying and executing of the meta trip that consumes such a disproportionate share of shorter journeys dropped away. Life became largely experiential, exactly what I needed.

So how do we pull off a trip like this? By realizing the importance of it, first of all. If we know that for the truth, then we commit to doing it, looking for the first responsible opportunity that comes along. After college, before family, after family, between careers or during mid-life crisis, to name a few popular windows. Don’t wait for retirement if you can do it beforehand. Make a plan and put it on the calendar. Defend it with your life. Do it, and do it alone.

This article originally appeared in Adventure Kayak, Early Summer 2013. Download our free iPad/iPhone/iPod Touch App or Android App or read the rest of the issue here for free.