Ever wondered what Canoecopia in Madison, Wisconsin is all about? Here is Rapid Media’s take on it with interviews of Darren Bush, Jon Turk and other paddlers who make the journey each year.

Daily Photo: Going In

“Hope you like this photo, it’s of my unplanned boat exit, on River Rothay, Lake District, UK.”— Paul Binks

This photo was taken by Tony Marsh. Want to see your photo here? Send to [email protected] with subject line Daily Photo.

Tahquamenon River Trip

This two-day itinerary is courtesy of the Tahquamenon Scenic Heritage Route.

A Liquid Landscape: Paddling the Tahquamenon Country of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula from Aaron Peterson Photography on Vimeo.

Day 1: Paddle the Tahquamenon River

Launch at dawn: Begin a six-mile, three-hour float at the M-123 bridge over the Tahqaumenon River just north of Newberry. Get an early start for the best chance at seeing wildlife like deer, otters and even elusive moose. Follow a gentle current as the river zigs and zags, taking you through deep forests, open meadows and quiet backwaters. End your trip at McPhee’s Landing. Hungry? Travel about 25 miles north of the logging museum to the Upper Tahquamenon Falls in the Paradise for lunch at the Tahquamenon Falls Brewery and Pub. After lunch, spend the afternoon hiking the trails of the Tahquamenon Falls State Park.

Day 2: Savor the Silence of the Pretty Lakes Quiet Area

Rise and shine: Pack your picnic and travel about an hour northwest from Newberry via M-123, County Road 407 and County Road 416. Arrive ar Oretty Lake. Paddle, portage, fish and swim in near silens for a few hours or an entire day. Explore more: Countinue north on County Road 407 and take in the sunset over Lake Superior at Muskallonge State Park.

Get more information about this route at: www.explorem123.com/recreation/paddling/

Daily Photo: A Mean Time in Greenwich

Rhode Island Canoe/Kayak Association paddler and Adventure Kayak reader Susan Engleman says this February day in Greenwich Cove, Warwick, RI, was “gorgeous—temps in the 30s, but with the bright sun shining, it felt warm and just so invigorating to be on the water.” Engleman and her paddling partner Earl MacRae had to break through the ice to get to open water. “That just made it more fun!” she says.

Want to see your photo here? Send to [email protected] with subject line Daily Photo.

Bay of Fundy Kayak Trip

This kayak trip destination is excerpted from “The East Coast’s Best 5 Places to Paddle” in Adventure Kayak magazine.

The Bay of Fundy

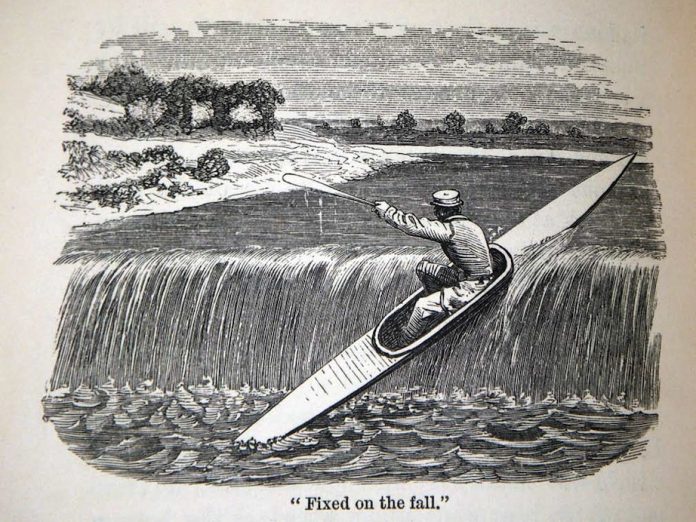

The Bay of Fundy is well known for having the most extreme tides in the world. With a maximum tidal range of 16 meters (53 feet) and current speeds of 30 knots, we were both impressed and somewhat nervous. For over a decade paddlers have been exploring many of the unique tidal features that form in the various river mouths. The most famous of these are the Reversing Falls located just minutes from downtown Saint John, New Brunswick, arguably one of the most dramatic bodies of tidal water in the world. We based a large part of our itinerary around these rapids and the Shubenacadie tidal bore to the north. The Reversing Falls threatened to spoil a few pairs of fresh undies, while the Shubenacadie proved to have some of the best longboat surfing we have ever found.

OUTFITTING: Committed 2 the Core, www.committed2thecore.com

This article originally appeared in Adventure Kayak, Early Summer 2009. Download our free iPad/iPhone/iPod Touch App or Android App or read it here.

Photo courtesy Flickr user mafue, licensed Creative Commons

The Dirt on Campsoap

This article originally appeared in Canoeroots and Family Camping magazine.

Penny-pinching campers and green-washing skeptics who wonder at the environmental merits of camp-specific “eco” soaps over Sunlight and Pert Plus, read on. The differences run deeper than packaging. But remember, all camp suds must filter through soil to allow bacteria to biodegrade the soap. That means no washing your dishes (or your hair, Fabio) in the lake—fill the camp sink and take it up on shore, at least 200 feet from any water.

Goat Mountain Skinny Dipper Delight Soap

No-rinse Shampoo/Body Wash

Dr. Bronner’s Magic Soap

Campsuds

Sunlight dish detergent

Ivory Soap

Apple Cider Vinegar

This article appeared in Canoeroots & Family Camping, Early Summer 2011.

Forward Sweep Kayak Technique

This kayak technique article on how to sweep turn while edging was originally published in Adventure Kayak magazine.

We sea kayakers earn every mile we travel, so we need all the paddling efficiency we can get. For turning, a forward sweep, which generates forward momentum as well as turning power, is more efficient than a stroke that has a braking effect on your kayak’s forward speed.

The power for sweep strokes comes from torso rotation, not independent arm movement. Initiate the forward sweep with your body wound up and your blade planted in the water at your toes. Keep your hands relatively low as your torso unwinds, pulling your paddle blade in an arcing path as far out to the side of your kayak as is comfortable, and ending within six inches of the stern of your kayak. Slice your blade out of the water before it touches the stern or it will get pinned against the kayak.

While the first third of the stroke is most effective for turning, concentrate on full, long sweeps, especially when practicing, to encourage torso rotation. Follow your sweeping blade with your eyes to make sure that you are actively twisting from the waist. As your skills evolve, you will naturally start to lead your turns with your head—looking where you are going, rather than watching your blade—but be sure to continue to use full and powerful torso rotation and not just arm movement.

For even greater turning potential, introduce some edging. Tilt your boat toward the side of the stroke (in the opposite direction that you’ll be turning), while keeping your head over the kayak. If you want to turn to the left, for example, think about weighting your right butt cheek and lifting your left knee while sweeping with the paddle on the right.

To balance with the boat on edge, use a climbing angle on your sweeping blade to create lift and support. This means that you hold the blade on about a 45-degree angle (power face downward) while sweeping it from the bow to the stern, effectively making it a combination sweep and high brace. Then recover the blade in a low-brace position, skimming the back of the paddle blade flat above the water, ready to supply support should you need it.

This article originally appeared in Adventure Kayak, Summer/Fall 2009. Download our freeiPad/iPhone/iPod Touch App or Android App or read it here.

Mountain Khakis Alpine Utility Pants Review

This gear review was originally appeared in Canoeroots and Family Camping magazine.

From Wyoming comes a new manufacturer with an old idea: use heavy, double-weave cotton canvas to make durable but supple outdoor clothing. Mountain Khakis’ Alpine Utility Pants are triple-stitched and have a double panel on the rear, knees and backs of the cuffs for long life. True, you don’t want to get them wet, but if day-tripping at either end of the season, these should be your pants.

$89.95 | www.mountainkhakis.com

This article appeared in Canoeroots & Family Camping, Spring 2009.