2012 Anti-oxidant Nut & Berry trail mix sells at Trader Joes stores for $8.99 per 12-oz. pouch and people actually buy it. Goodbye, old raisins and peanuts.

2011 Another Fork in the Trail, by Laurie Ann March, is the first backcountry cookbook for vegans.

2010 Elizabeth Gilbert’s best-selling, round-the-world memoir Eat, Pray, Love is adapted into a film starring Julia Roberts, which grosses over 200 million at the box office. Portland-based feminist magazine Bitch criticizes Gilbert’s message in an article called “Eat, Pray, Spend”.

2005 Following Hurricane Katrina, a sudden growth of MREs (Meals, Ready-to-Eat) listed for resale via online auctions leads to the media dubbing them Meals, Ready-for-eBay.

1994 Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics is founded. The fifth of seven LNT principles: Minimize campfire impacts.

1984 “Weird Al” Yankovic’s parody song Eat It snags a Grammy for Best Comedy Recording and reaches number one in Australia, topping the MJ original by two spots. Have some more yogurt, have some more spam / It doesn’t matter, if it’s fresh or canned / Just eat it. Amen.

1983 Michael Jackson’s Beat It tops the Billboard Hot 100 for six weeks, and in just over a year Thriller becomes the best-selling album of all time.

1981 The U.S. military replaces the venerable canned C-ration with lighter MRE pouches. Flameless ration heaters are introduced in 1992, biodegradable cutlery in 1994 and vegetarian options in 1996. Thrifty campers stock up on surplus tins of Vietnam War-era beef ravioli.

1938 Developed during World War II to preserve serum for transport to field clinics in Europe, freeze-drying is adapted by Nestle for use in the food industry. Fifty years later, Bill Mason sings the praises of preservative-free, freeze-dried meals in Song of the Paddle.

1936 Jell-O launches enormously popular chocolate pudding mix; 30 years later, the No-Bake Cheesecake is an instant hit among sweet-toothed campers.

1909 The word “spork” appears in the Century Dictionary, 35 years after the first patent is granted for a spoon-fork hybrid.

1896 Victorinox founder, Karl Elsener, receives a patent for the Officer’s and Sports Knife, an early Swiss Army knife featuring large and small blades, screwdriver, corkscrew, can opener and reamer.

1884 The invention of peanut butter is credited to a Montreal physician seeking a high-protein food for the toothless and elderly. Some four decades later, pioneering peanut proponent, George Washington Carver, does much to raise the status of the underappreciated legume.

1870 Salt pork is the staple diet of French Canadian voyageurs paddling the fur trade route between Montreal and Grand Portage, leading to the derogatory nickname mangeurs de lard.

1810 In answer to a 12,000-franc cash prize offered by the French military during the Napoleonic Wars, canning is invented as a new method of preserving food. Unfortunately for Napoleon, the war ends before the process is perfected. Even more unfortunately for his soldiers, the can opener is not invented for another 30 years.

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2012 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

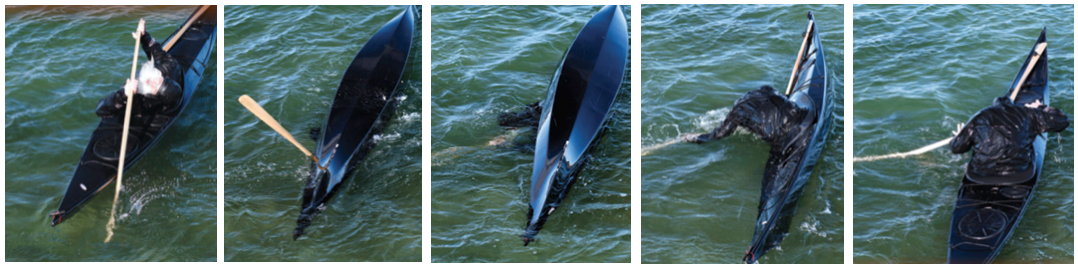

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2012 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2012 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

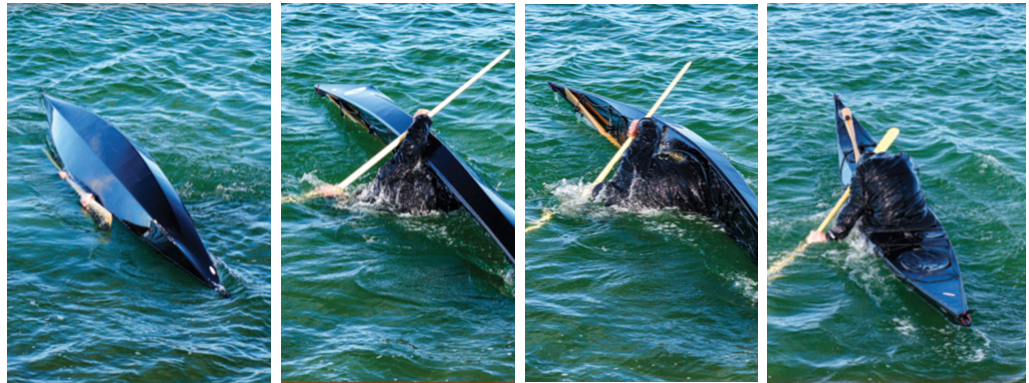

This article first appeared in the Summer 2012 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Summer 2012 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions