I rarely see my friend Jon any more. We’ve sea kayaked together for years, and he’s been a fixture in the open-ocean paddling community. But he’s disappeared. Disappeared into a canoe, and it’s all the fault of the Brits.

The new requirements of the British Canoe Union—in which Jon and many of my other sea kayaking buddies are coaches—require competency in multiple paddling craft and environments. Longtime sea kayakers had to cut their paddles in half and start kneeling in open boats on rivers.

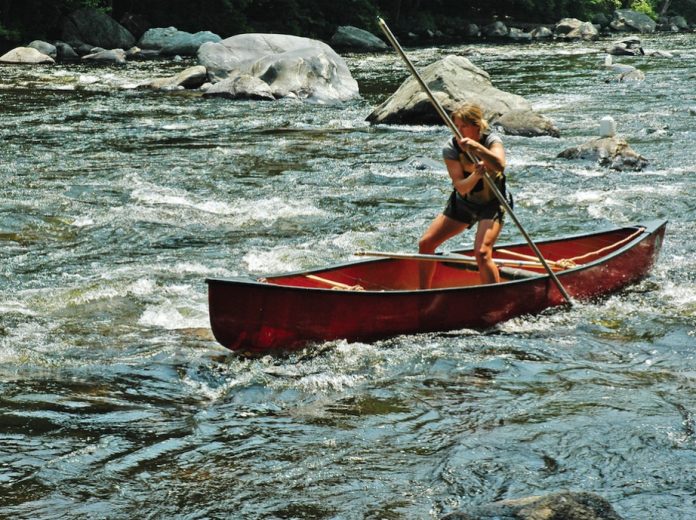

Jon loves it, he’s addicted to half a paddle and boats that fill up with water when you crash through waves. He now has six canoes outnum- bering his kayak fleet.

So I did what anyone would in my situation—complain. Why does coaching sea kayaking require knowing how to canoe?

Of course, there are plenty of good reasons. Coaching means working with other sports in a student’s history, and canoeing is a common one. Coaches employ a variety of techniques to provide feedback to learners: using half a paddle is very effective. I’ve been in tight rock gardens where

I could only paddle on one side of my kayak anyway.

I stopped whining about my lack of partners for sea kayak adventures, dusted off my ancient whitewater kayak (two knee surgeries make kneeling in a canoe impossible), and joined them on the river.

“For every kayaker who starts canoeing, a canoeist must start kayaking.”

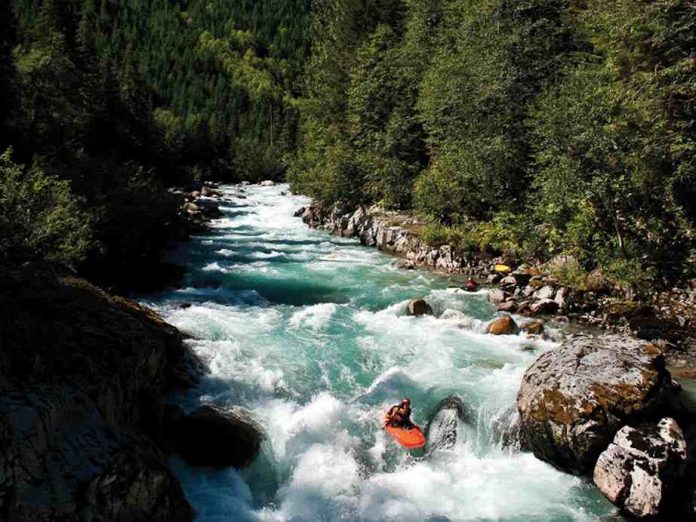

Soon I was hooked. Half an hour from home, the water was clear and clean, and the current pushed us along from one play spot to another. I upgraded my whitewater kayak and went on a seven-day river trip with my now kayaker-canoeist buddies. We didn’t once have to wake up at 5 a.m. to catch an inconveniently scheduled tidal current.

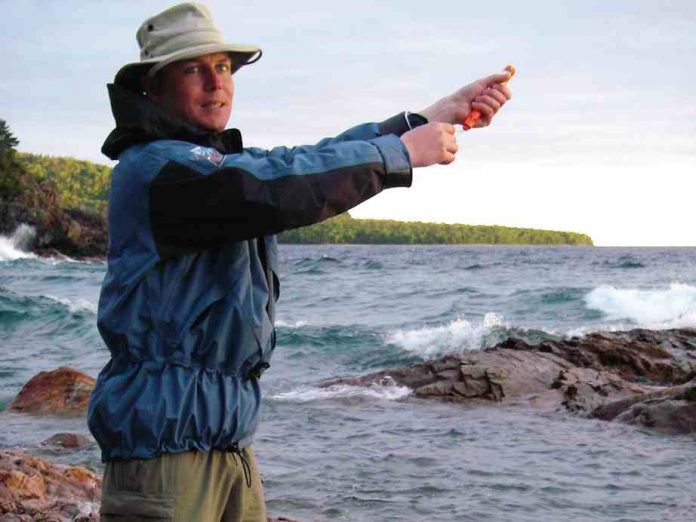

Then something even cooler happened. Suddenly, new river-rat friends wanted to go sea kayaking. Diehards from the single blade scene bought NDK Explorers and asked me about trips in British Columbia and Alaska. It was as if there was some Newtonian Law of Conservation of Paddlesports Disciplines I’d missed in high school physics, where for every kayaker who starts canoeing, a canoeist must start kayaking.

That also makes sense. When sea kayak coaches started canoeing, whitewater open boaters suddenly found themselves sharing eddies and shuttles with sponsored, 5-star kayakers with some hefty trips under their belts. The allure was irresistible. The sea kayaking industry couldn’t have come up with a better way to expand their sport.

Now I sea kayak with people who tell stories about open boating down the Grand Canyon. I recently watched a canoeist-turned-sea kayaker pull off a back ferry across Canoe Pass that his instructor couldn’t mimic. As the saying goes, “Advanced sea kayak strokes (like cross-bow jams) are basic canoe strokes.”

I see my old sea kayaking friends again. It’s anyone’s guess what kind of boats we’ll be paddling.

But these days Jon is really into poling—pushing his way upstream in a canoe with a 12-foot-long stick. I doubt that will catch on. It sounds kind of silly.

Neil Schulman lives, writes, paddles, photographs and works in environmental conservation in Portland, Oregon. He owns four kayaks and no canoes…yet.

This article first appeared in the Summer/Fall 2011 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Summer/Fall 2011 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.