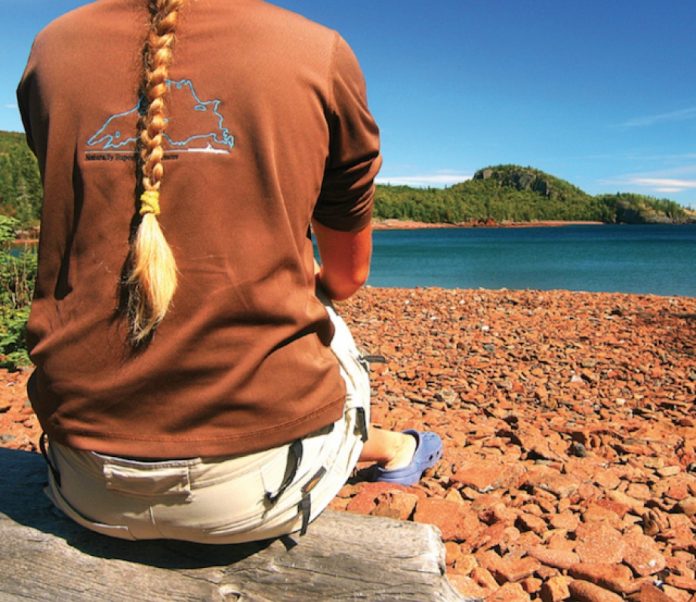

DREAM BIG AND FOLLOW THROUGH

Last summer, Minnesotans Lucas Will and Greg Petry fulfilled a dream five years in the making, to sea kayak around Lake Superior. Here’s how they found the 97 days to get it done: “It was easy for us to drop everything because we had little to drop. We work sea- sonally as outdoor educators, so getting time off meant we just didn’t apply for the next job on the list. In order to follow a dream it first needs to be identified. Then you can start making the choices to turn that dream into reality. In the end, we didn’t drop everything, we purposefully put things down in a place where we’d know where to find them when we got back.”

Above photo: Ryan Creary

HANDLING INTERNATIONAL LOGISTICS

New York-based paddler Marcus Demuth makes a point of going to places where sea kayaks haven’t been, which throws a wrench into logistical planning. In the case of his 2010 expedition to Tierra Del Fuego,

Chile, it meant he and expedition partner Biff Wruszek had to practice their spanglish to figure out how to get sea kayaks to the tip of South America, find charts for an obscure coastline and secure travel permits.

“Until recently, three-piece sea kayaks could be transported on commercial flights. Now fiberglass boats aren’t allowed. This is something I’m willing to take a chance on— how is the baggage handler going to know my kayak isn’t made of plastic? The other option is to send your boat on a container ship. This works great if you don’t mind dealing with high costs and inevitable delays, which seem to range from weeks to months. Or you could use a folding kayak, but in my opinion they don’t offer the big water performance of a hardshell.

“In Chile we were lucky to hook up with a few local paddlers in advance through Facebook and they helped us out big time. We tend to think of the Internet as our best source of information but Biff found charts for our trip by writing letters with pen and paper. Of course you could always go to a more popular destination—my trips to Great Britain, Iceland and Ireland were dead easy to plan.”

FILM YOUR TRIP, OR NOT

Newfangled digital camcorders, HD-capable digital SLRs, helmet cams and pocket-friendly point-and-shoot cameras make high-quality filmmaking equipment accessible for the masses. The real question is, do you want to do it?

Paddlesports filmmaker Justine Curgenven has made a living toting camera gear to the watery ends of the Earth. She offers this advice: “Small mountable cameras like the GoPro Hero and the Oregon Scientific ATC9K allow the keen kayaker to bring the experi- ence home to their friends in high definition. The challenge is getting the best out of these cameras and creating a story from the foot- age. You have to learn the limitations of a camera and work out ways to get around them: Don’t film into the sun. Treat your lens with a water repellent like Rain-X and have a cloth handy to wipe drops off. The main thing is to practice before you really want to film something. You will make mistakes, so make them when it doesn’t matter.

“The main downside of filming an expedition is that the process is tiring and it can take the focus away from the experience of the trip,” Curgenven admits. “When I’m exhausted I don’t want to pick the camera up and think about capturing a sequence of shots. When dolphins leap into the air beside me, it would be nice to just sit and watch rather than grab for my camera.”

Above photo: Phil Tifo

GROUP DYNAMICS

When Norwegian sea kayaker Simen Havig-Gjelseth assembled a team of paddlers to attempt an unsupported circumnavigation of Antarctica’s South Georgia Island, personality trumped paddling skills according to his list of requirements. “It is more important that the person can work in a group, creating a nice atmosphere and not complaining, rather than being an Olympic champion in paddling,” notes Havig-Gjelseth, who went so far as to insist that all four paddlers sleep in the same tent to ensure decisions were made as a group. The strategy worked. In November 2010, the Norwegians became the first to paddle around South Georgia’s rugged 650-kilometer perimeter without external assistance.

SAFETY AND RESCUE

I nstructors and expedition paddlers Shawna Franklin and Leon Sommé, co-owners of Washington-based Body Boat Blade International, like to divide safety gear into group (first aid kit, boat repair kit) and individual (VHF marine radio, flares) items. Franklin doesn’t hesitate when asked which piece of safety gear she’d never leave behind on an expedition: a tow system. “We use tows all the time. On the south coast of Iceland, Leon came out of his boat on a surf break. I was able to tow him and his boat through the break to perform a rescue. Later on the same trip, we used a tow to assist a seasick paddler. It is important that everyone on the trip has a tow system and knows how to use it; we wear ours on our waists.”

TRAINING AND FITNESS

Sea kayaker Joe O’Blenis knows a thing or two about making the most of limited vacation time. Last year, O’Blenis reclaimed his speed record for circumnavigating Vancouver Island, completing the 1,150-kilometer expedition in 16 days. What could’ve been agonizing was made enjoyable by a pre-trip training strategy. “I didn’t get to train as much as I wanted to,” says O’Blenis. “I planned on doing lots of long, eight- to 10-hour train- ing days. But in reality I didn’t have time to do that.” Instead, O’Blenis relied on intense two- to three-hour on-water sessions, including intervals and time trials. His secret weapon in developing speed, power and ultimately stamina was training with a wing paddle. “I had no intention of using it on the expedition,” he says. “The idea was that when I switched back to my normal touring Greenland-style paddle it would feel effortless.”

Above photo: Virginia Marshall

HAULING THE WEIGHT

Sommé insists that if you think like a backpacker you’ll never run out of space when packing your boat. Break down your tent into individual components; pack clothing and gear in small drybags; avoid doubling up on group gear like pots and stoves; buy the most compressible sleeping bag you can afford; and do a few dry runs at home so packing doesn’t take all day at the put-in. Sommé is not a big fan of packing things in his cockpit for fear of losing gear and hindering re-entry in the event of capsize. He makes an exception on ocean trips in arid regions where fresh water can be the heaviest item in the boat. Here, Sommé rigs a through-the-deck hydration system behind his seat, storing bags of water close to the bulkheads.

THE EXPEDITION PADDLER’S MENU

Food is often the distinguishing factor between a recreational trip and an expedition. True, you can go gourmet on a long-haul, multi-day journey, but “after paddling six to 10 hours a day the last thing you want to do is prepare a five-course meal,” says Sommé. Franklin and Sommé prefer easy to prepare, one-pot meals that they “can eat over and over,” without gagging or getting malnourished. Typically that means combining lots of carbs with a source of protein and fat like olive oil or gobs of peanut butter. Hard-boiled eggs and dried sausage are staples on Franklin and Sommé’s lunch menu. But that doesn’t mean you can’t eat fresh. “One of the best things we did on our Haida Gwaii trip was a cabbage salad,” says Franklin. “Cabbage keeps forever and by combining it with apples, carrots and an oil and vinegar dressing, it makes a great side dish.”

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2011 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2011 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.