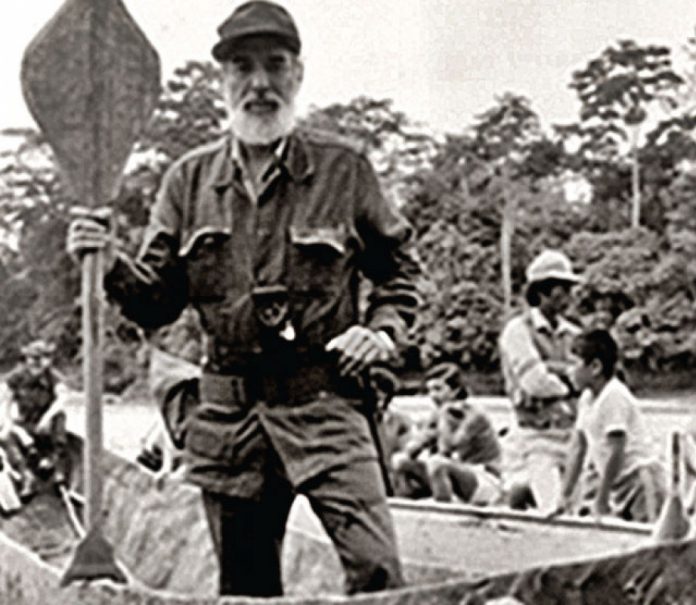

“Draw! Draw! Forward hard! Hard! Hard!” Taku has never been on a canoe trip before so I call out his strokes like a coxswain. He reacts instantly and the canoe slips around a pillowing rock the size of a Smart car before we bash through a series of waves that high-five Taku’s face.

With his hair slicked back into a pompadour care of the Albany River, Taku looks like an Elvis impersonator from Tokyo as we spin into the eddy. Born in Japan and raised in the dirty streets of Chicago before becoming a West Coast boy, Taku had been slow to try out the oldest North American pastime. From backcountry skiing with him in B.C.’s Coast Mountains I knew he had the temperament required for an extended wilderness trip so I asked him along on my 75-day paddle through the boreal forest—there’d be plenty of time to teach him about canoeing along the way.

Five seven five. Every evening by the water Taku writes haiku in Japanese and Chinese characters using a brush dipped in a well of black ink. We’re 25 days in at the base of Kagiami Falls on the Albany River. Taku sits and writes. His newness to tripping is refreshing—everyday he learns something, sees it in a different way than I do. I want to learn more from him so I press him on his ritual. Looking up from his script to the setting sun, the words come calmly.

“Your daily existence in the boreal is simple—it consists of moving forward and doing what’s necessary for survival and comfort. In the city, all the annoying details of life are a distraction. The isolation of the wilderness removes the clutter and makes me more reflective and meditative.”

He glances at Kagiami Falls then returns to his haiku. In a few words, he has captured this place. Five seven five.

Our 3,100-kilometre trip began in downtown Winnipeg. Carrying our gear down the aptly named Portage Avenue, we parted gawking lunchtime crowds and put in at the Red River. Our route would take us to Parry Sound on Lake Huron’s Georgian Bay via Lake Winnipeg, the Bird River, Woodland Caribou Provincial Park, Lac Seul, Lake St. Joseph, and the Albany, Kenogami, Kabina, Pivabiska, Missinaibi, Mattagami, Grassy, Sturgeon and French rivers. The route dances above and below the 51st parallel, the partition that separates pristine boreal forest in the north from the industrialized south. It’s a line on the map you might be hearing more about soon.

A globally significant swath of green, the boreal is like a giant carbon bank, holding 67 billion tonnes of the element in deposit.

In summertime, worldwide carbon levels measurably drop as this great lung of our planet takes in a deep breath for us all. Due to its remoteness, the zone north of this latitude remains the greatest area of undisturbed boreal forest in Canada. The First Nations of this region called for a moratorium on development in 2005 as forestry, mining, and hydro interests began creeping north.

On day 21 we pick up our food parcel from the post office in the Mishkeegogamang First Nation at the head of the Albany River.

The owner of the general store is a sharp-featured woman with dark, curly hair named Laureen Nassaykeesic. She is a former member of band council, well versed in local politics and firm in her opinions. Laureen speaks softly as she twirls a daisy in her hand. “We are prepared to fight to make sure they don’t come and develop the area. The only benefit would be a stumpage fee, which would be nothing. Then, what, wait 100 years for a new set of trees? I have grandchildren and I’d like them to enjoy the green forest and the natural way of things. We’re very lucky to live here.”

Taku is wolfing down pork chops and mashed potatoes provided by our host Norman “Dude” Baxter. We are one week down the Albany at the Marten Falls First Nation. Dude is a fishing and hunting guide with a drill sergeant buzzcut. He found Taku wandering around the village and invited us in just as a ferocious sideways storm swept in. Sixty years ago, his father would spend two weeks paddling from Marten Falls to Calstock to trade furs for supplies. There are no roads even today, just waterways.

“The Albany is our highway,” Dude explains. “It gives us our fishing and hunting—it’s everything.”

Despite the Albany’s status as a provincial park, the Ontario Power Authority has proposed that two major dams be built on the river by 2020, one of them at Kagiami Falls. The projects would carve up the surrounding boreal wilderness with roads and transmission lines as well as flood existing habitat and hunting grounds. A current agreement between the province and First Nations limits power projects above the 51st to 25 megawatts but as power demand increases, so does pressure to renegotiate the deal. Apparently everything is negotiable; everything is on the line.

The first big boulder to catapult its way into the region is the Victor diamond mine on Ontario’s Attawapiskat River, spearheaded by international giant de Beers. The project, already underway, will clear 5,000 hectares of forest, generate 2.5 million tonnes of leeching waste per year and pump 100,000 cubic metres of salty water from the pit into the attawapiskat daily. In all, the entire project will affect an area 22 times the size of Vancouver. All for a mine forecast to produce for only 12 years.

Rounding the corner at the confluence of the Missinaibi and Mattagami rivers we turn away from James Bay and head back upstream into the heart of the Boreal. Taku is not the only one being meditative. Staring down 450 kilometres of upstream paddling makes you live in the moment, fixating on how each stroke—and all too often each stride—gets you closer to the next height of land.

Taku’s head is down as he tracks the canoe and stumbles repeatedly over sharp, slippery rock. The wide, shallow Mattagami River is too low to paddle and seems to stretch endlessly ahead. We are travelling through the industrialized wilderness that exists south of the 51st parallel—still remote, mostly unseen and yet bent sharply by our desires. there was little joy yesterday and today is the same. Taku’s haiku tonight will be a sad one.

The Mattagami drops and rises based on the electrical demands of people who have never heard of it. the water is coffee-coloured with brown foam lining its edges—like a bowl of cappuccino. Fish are inedible due to mercury leeched from flooded ground, upstream mines and mills mean drinking water has to be drawn from feeder creeks.

On the morning of our third day up the Mattagami I peer through the mesh of our tent to the other side of Grand Rapids, but the river is gone. All i can see are piles of broken limestone. Wet streaks between rock piles are the only indication that this was a river the day before.

Three hours later, galaxies of lights and computers turn on far to the south as the workday kicks in. Four unseen dams release and water begins to fill the quarry-like riverbed. It steadily bubbles back to life. The level rises half a metre—enough for taku and i to begin our slog for the day, looking around each point for a feeder creek to fill our water bottles. We pull our canoe up the rest of this formerly great rapid, one the voyageurs used to sing songs about as they pushed to James Bay.

As the collective demand for more comes from the south the Mattagami responds and by midday the water is deep enough for us to paddle. the river is running hot now—an alien high tide with the power grid acting as full moon.

We paddle hard against the steady outflow.

Hugging the shore, we strain through the current at the tops of eddies. Sometimes the paddle strokes seem futile, and i think of the Albany. Sitting in a 16-foot canoe I felt helpless against the current of that great river; on the Mattagami i feel helpless against the current of a society that seems bent on pushing ever deeper into wilderness.

But we keep cranking, because if more people know about what the Albany is like, and what the Mattagami has become, there will be hope for the boreal above the 51st. Stroke after stroke we strain against the current. We know easing up means going backward.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2008 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Fall 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions