It took a trip to Cuba for me to appreciate, a quarter century later, the legitimate genius of Don and Dana Starkell’s canoe trip from Winnipeg, Manitoba, to the mouth of the Amazon River.

I was invited to Cuba by the Foundation for Nature and Humanity to help develop a training program for environmental teachers. All was on track until my host casually referred to Cuba as a “canoe culture.” If I looked surprised when he said that, I was speechless when he said, “If you don’t believe me, come check out our canoe museum.” Canoe museum?

There in a back room of the foundation’s Havana office was one glorious canoe—a 42-foot dugout canoe called Hatuey (named after Cuba’s first national hero, a Taino Chief who had warned the residents of Cuba of the impending arrival of the Spanish in the early 16th century). Inside the canoe were paddles carved in exotic rainforest leaf patterns. Surrounding it, in glass cases that lined three walls, were fascinating Latin curios including a still-menacing stuffed piranha and, so my host said, the world’s largest collection of erotic pottery. So they not only had a canoe museum, they appeared to have a Cuban angle on the whole love-in-a-canoe theme as well!

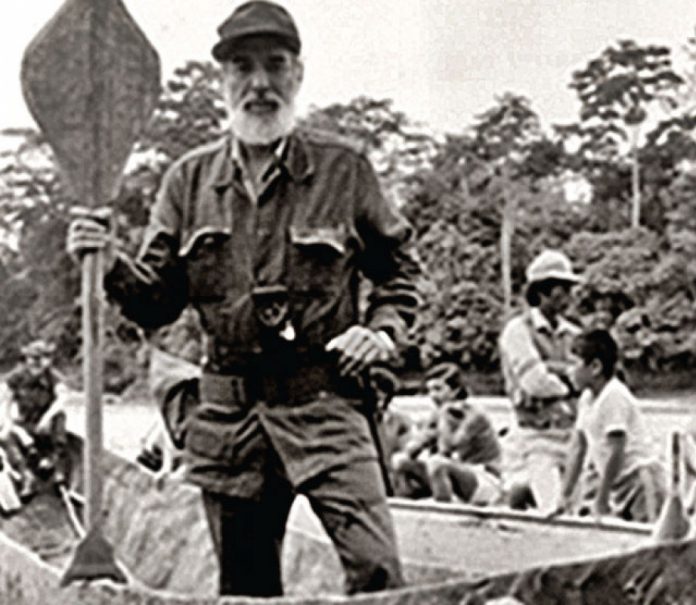

But the story got better. In the years leading up to the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ conquest of the Americas, Antonio Nunez Jimenez, the scholar and naturalist who had inspired the creation of the Foundation for Nature and Humanity, decided to play down the European “discovery” of the New World and celebrate instead how people came to Cuba in the first place, long before 1492. That migration, research revealed, was by canoe from high in the Andes in what is now Ecuador.

So they not only had a canoe museum, they appeared to have a Cuban angle on the whole love-in-a-canoe theme as well.

Jimenez commissioned five 42-foot dugout canoes and corresponded with people all along the migration route. In the late 1980s he led an historic reenactment of the founding canoe trip, down the Napo River to the Amazon, along the mighty Amazonas to the junction of the Negro River, then upstream to the height of land in what is now

Guyana, over the divide, and down the Orinoco River to the Caribbean Sea. There, they tied outriggers on their canoes and made their way over open ocean among the Antilles and eventually to Cuba.

As I stood at a map in the Cuban Canoe Museum, listening to my host recount this amazing tale (and yes, he explained how the erotic pottery, the canoe, and a powerboat called Love all factored into the story), I recalled that this term “canoe” that is so near and dear to the hearts of Canadians is likely indigenous to the Caribbean, probably derived from the Arawakan term, canaoua. I wondered why we acknowledge that north-south linguistic connection so rarely.

So often Canadians assume we have the corner on all things canoe. True, considering our own history and the role that the canoe, particularly the uniquely Canadian birch bark canoe, has played as an east-west transportation and communication link, there is a temptation to think that there ends the story. Not so. Remember that crazed guy from Winnipeg who loaded his two sons in a 22-foot fibreglass canoe called Orellana and set out for the Amazon?

It took them two years. One Starkell son bailed out near the Gulf of Mexico. But Don and Dana Starkell covered a large portion of the route through South America that Jimenez and his crew would travel a few years later, rejoining the historic canoe connection between North and South America. Starkell, in his bones, knew that our canoe culture and theirs were related, and that to understand one, we are obliged to appreciate the other.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2008 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Fall 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions