I think I was seven when all my parents, uncles, aunts, siblings, cousins and I shuffled into a small main street studio. It was a stuffy low-ceilinged room lined with benches, strobes and an autumn-scene canvas backdrop.

The family portrait, commissioned by my grandparents, still hangs in their hallway, a reminder to me to never dress up a skinny seven-year-old boy and his extended family and stand them in front of a two-dimensional, neutral-grey-toned wilderness and expect them to look natural.

Portraiture, in the art world, happens when a painter depicts the visual appearance of his subjects. Just about any photograph does this, but a true portrait is more than that. A true portrait captures the essence or personality of the subject, not just a physical likeness. Think of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, perhaps the most famous painting of all time. Without that smile she’d just be another Wal-Mart portrait.

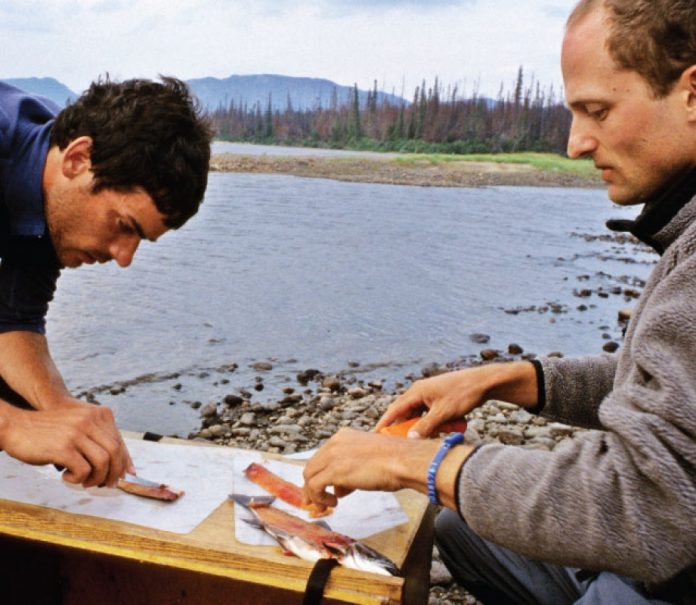

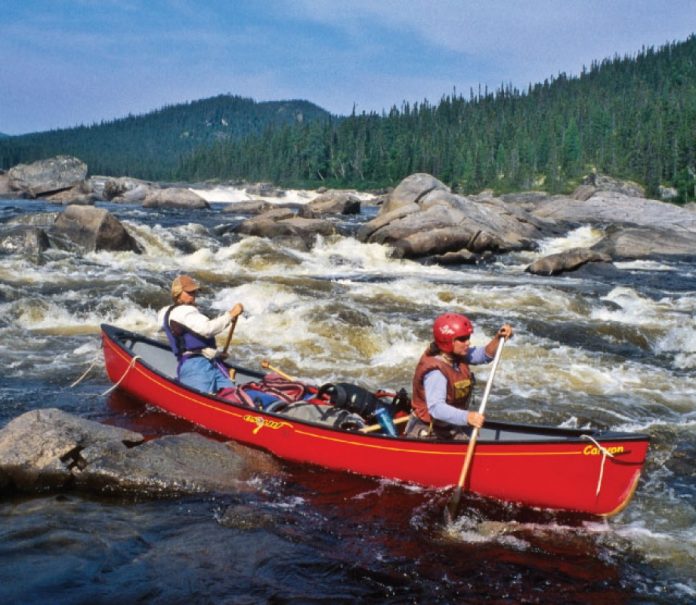

For this issue’s feature I asked our regular Family Camping photographers for tips on taking pictures for family albums. There were a few technical camera tips for making better photographs but most of the suggestions had nothing to do with buttons on the camera. Great outdoor portraits are more about natural environments, props, and simply standing back, and letting inner essences bubble to the surface.

Some of my favourite family portraits simply capture a moment in time. Like our first cross-country ski trip; skinny dipping in the river; or the smile on my daughter’s face with her first mouthful of roasted marshmallow. Time stops for no man. But I can hang a fraction of a second of it on my wall.

Other pictures I’m excited to show my kids in 10 or 20 years. I want to show them what they were too young or too busy to remember. I want to show them who they were. It’s one thing to tell them they loved jumping in puddles, it is another to show them mid-air and screaming.

And, there’s legacy. My legacy. My vain and backslapping ego wants my kids to know just how cool their good ol’ dad really is (or at least was). I actually grew my hair and beard, so they’d have photos of us together like this. I hope by digging through old shoeboxes of pictures (or scanning through DVDs) they’ll see just how much their parents love them. Never before have parents had the luxury of spending as much time with our kids as this generation. I want them to see the adventures we had while raising them.

When I was growing up my parents, like most of their generation, were busy. Cameras and film were expensive, and not very handy to use—flash used to come in disposal cubes. Consequently, there are only a few cherished pictures of me, and even fewer of my younger brother.

After three years of parenthood I have more than 2,400 family photos on my laptop. Only a couple are as good as those taken by our pros. A few more are special enough to hang in our hallway. But I guarantee you this, not a single one has an unnatural smile in front of a fake forest background.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions