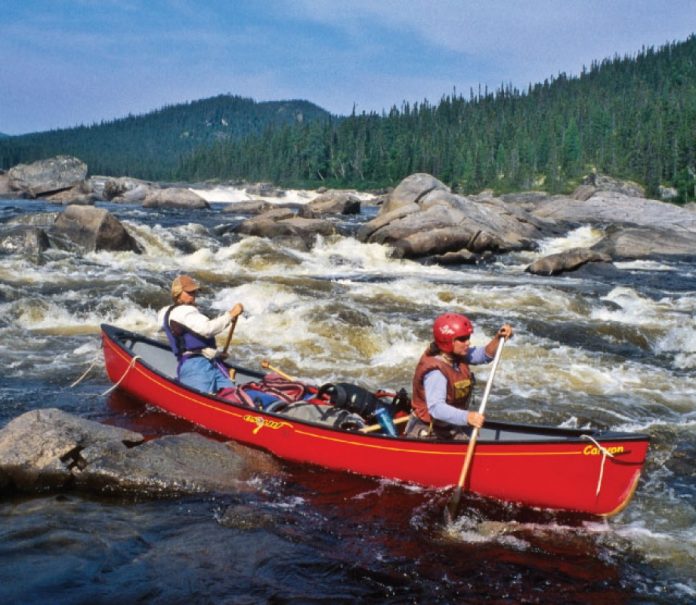

Fran Bristow hopes you use this canoe buyer’s guide to buy a canoe. She has no financial interest in the matter, she just knows you’ll need one to paddle the Romaine River this summer. And she passionately believes you should paddle the Romaine.

I first heard from Bristow last spring. She was working for an outfitter and looking for a new river to paddle. She had read a Canoeroots article I had written about a trip on Quebec’s Romaine and wanted to know more. With a certainty usually reserved for the religious I told her to paddle it—because it is even more beautiful than challenging, and because time might be running out.

Getting more paddlers on the Romaine is one part of Bristow’s campaign to publicize Hydro-Québec’s plans for the river. After paddling the Romaine last summer she banged on the door of the Sierra Club’s Quebec chapter and told them that with their help she was going to make sure more people knew what will be in store for the river if the corporate-ladder-climbing engineers at Hydro-Québec get their way. She is spreading the word through the media, wading into an environmental assessment process that makes the Romaine’s lengthy rock gardens look easy and trying to get as many people as possible to see the river from the seat of a canoe.

Her drive is inspiring, but her task is daunting. Hydro-Québec operates under few constraints. If it wants to skip environmental assessments, then the provincial government writes a law allowing it to do so. It often goes through the motions by commissioning the studies required by environmental assessments, but since the presiding authority for those assessments is the same provincial government that receives more than a billion dollars a year from Hydro-Québec, the outcomes rarely surprise anyone. The government gets paid when Hydro-Québec dams rivers because it happens to be the only shareholder of this for-profit corporation.

It would be easy to see the Romaine as doomed by this political-economic juggernaut. Hydro-Québec has already spent millions surveying sites for four planned dams, which together would effect a $5-billion transformation of this river into a 270-kilometre-long series of reservoirs extending nearly the whole way from the Gulf of St. Lawrence north to Labrador.

A Hydro-Québec spokesman told me that the 1,500 megawatts of power expected from the Romaine are needed to stave off a looming power shortage in Quebec. Except that their own 2004-2008 strategic plan indicates that 45 per cent of the power they produce is exported to Ontario and the United States. And in January Hydro-Québec started paying a subcontractor to mothball a brand new power plant near Trois-Rivières because of oversupply in the provincial power grid. I’m beginning to doubt the man’s honesty—and the need for the Romaine project.

It’s a mystery how some environmental causes gain momentum among people and plow through even the most comfortably entrenched political and commercial fronts. But it happens.

If enough people buy into Bristow’s campaign to save the river, perhaps the Romaine will remain, as it has for thousands of years, a wild and beautiful river, and not become just the latest victim of the widely destructive coupling of ambitious Hydro-Québec engineers and their venal political enablers.

With Quebec’s present overcapacity of power, and with the enormous potential of energy conservation now being appreciated across the continent, maybe Bristow is starting her campaign at just the right time.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great boat reviews, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great boat reviews, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions