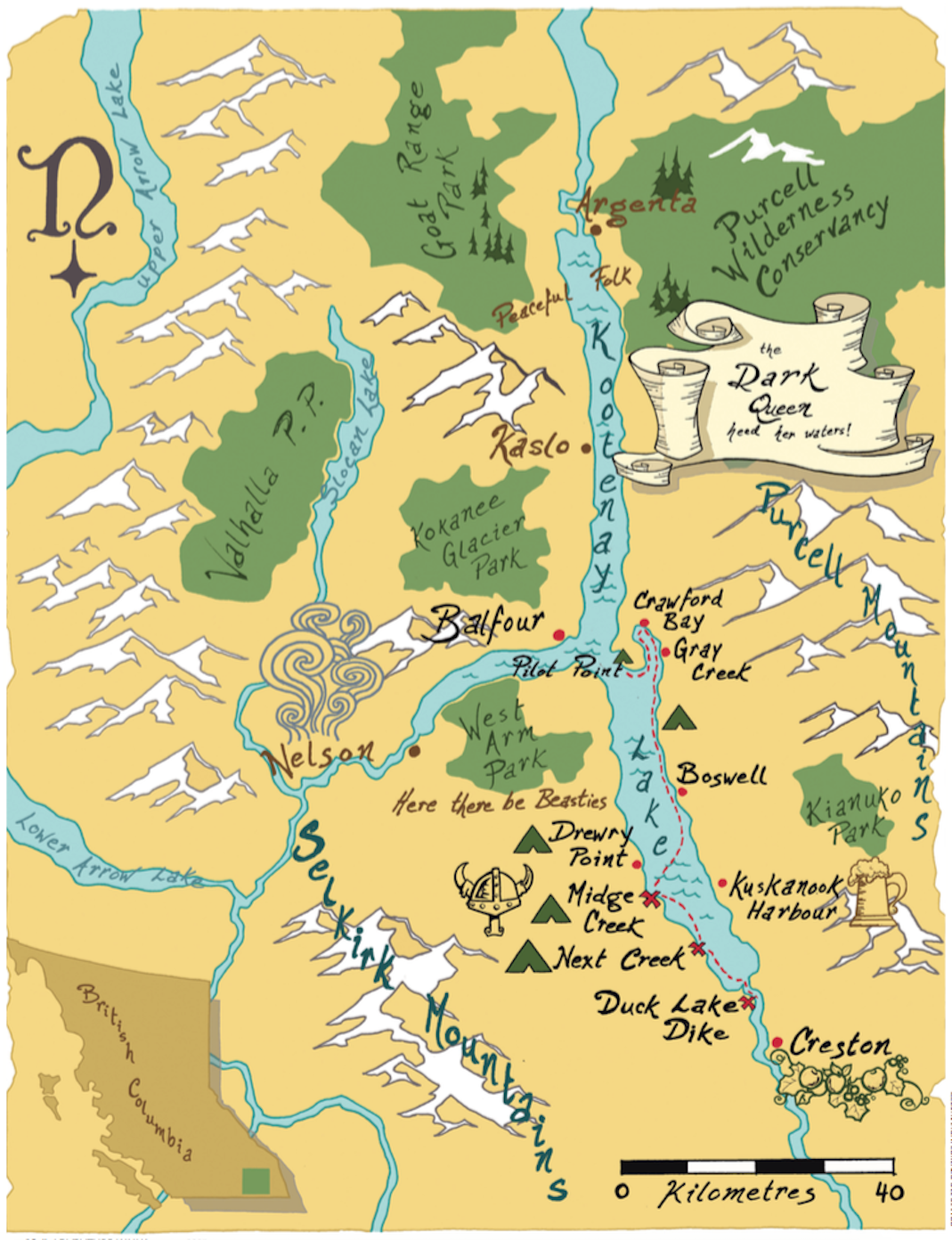

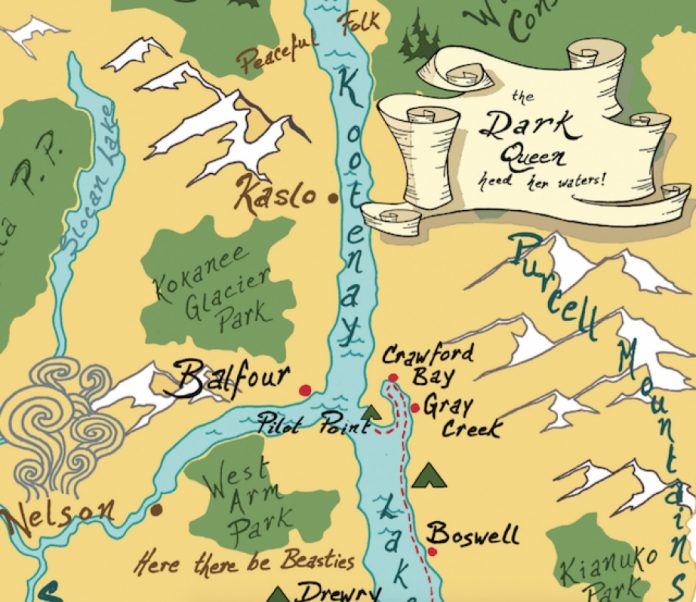

In the Kootenay region of Southeastern British Columbia, the lithic ramparts of the Rocky, Purcell and Selkirk mountains soak their feet in deep, cold lakes held fast by steeply treed slopes. Upper and Lower Arrow Lakes, Slocan Lake, Windermere Lake and dozens of smaller lakes and reservoirs fill nearly every valley. The greatest lake of all, the mother lake, is the Dark Queen herself—Kootenay Lake—the largest natural lake in southern B.C. Nearly 150 km long, this massive inland sea leaves a bow-and-arrow-shaped footprint on the region even larger than her massive blue figure on maps.

The Dark Queen of the Kootenays has it all: superlative fishing (including the largest rainbow trout in the world), soul-soothing mountain views, water pure enough to lift straight to your lips, and a rainbow of colorful communities where you can counterpose a day of paddling with an evening of live jazz or a night in a B&B.

The Dark Queen’s many moods

Nestled comfortably in the cradle of the Selkirk and Purcell mountains, Kootenay Lake has a wild side that belies her seemingly protected nature. Countless side drainages funnel glacier-born crosswinds onto the north-south oriented lake, resulting in exciting and dangerously turbulent waters. Stories abound of boaters drowning or disappearing into her icy depths. Paddlers and fishermen alike know to look to the horizon often and carefully, watching for the telltale black line that signals a change in the Dark Queen’s mood—for the worse.

The lake’s many moods have helped shape the culture of the villages anchored like floats on a fishing net around her perimeter. Each has more than its share of artisans, musicians and outdoor enthusiasts drawn to, and inspired by, the disposition of the Dark Queen.

On the outflow of the lake’s West Arm, the city of Nelson is known globally for its proximity to wilderness and for the quality and availability of some of the best “bud” B.C. has to offer. Not many 7,000-person towns have their own police force, or the staggering array of outlets for expendable income. High-end coffee shops, quality restaurants and trendy sporting goods stores line Baker Street in downtown Nelson, and most locals openly admit that it is income from the underground marijuana economy that is one of the critical drivers of this thriving social scene. Whatever the reason, paddlers can always find a good café, restaurant or live music in Nelson at the end of a great day on the water.

Loggers, orchards and 200 km of freshwater paddling

The small town of Creston lies not only at the far end of the South Arm, on the Kootenay River just before it enters the lake, but also at the polar opposite end of the socioeconomic spectrum from Nelson’s trendy, affluent scene. Steeped in a quaint 1950s air, the Creston Valley supports a unique mix of hard core loggers and fundamentalist right-wing Mormons from the nearby community of Bountiful. A surfeit of senior citizens meander the streets at a septuagenaric pace, and the town has the anachronistic air of a community clinging stubbornly to the last echoes of an unsustainable forest-based economy. Ironically, in the agricultural paradise of the Creston Valley—filled wall-to-wall with apple and cherry orchards, asparagus fields and blueberry patches—the town’s one great restaurant, the Other Side Café, is rarely open (update from 2020: the cafe is now permanently closed).

Between Nelson and Creston lies over 200 km of wild freshwater paddling through remote wilderness. White-sand beaches at Laib and Midge Creeks contrast with the steep granite bluffs that protect much of this backyard paddling paradise. An 8-km, bushy hike up Midge Creek north of Creston will lead you to some of the finest remaining Kootenay old growth forest, while the gruelling Lasca Creek and Mill Creek trails offer access to the alpine of West Arm Provincial Park to only the most committed hikers. Paddlers will share this wilderness landscape with some of the world’s last remaining endangered mountain caribou (as few as 60 of these shy, old growth–dependent ungulates remain in the heavily deforested south Kootenays), as well as the odd grizzly, wolf, secretive cougar—or even a wildly bearded and dread locked West Kootenay local.

At the far end of the northern reach, Kootenay Lake fills the front hards of Kaslo, Argenta and a handful of remote, independent communities. Up here the Dark Queen wears a different robe. Her mountain companions are steeper, higher and more rugged. Summits in neighbouring Goat Range Provincial Park and the Purcell Wilderness Conservancy reach skywards over 3,000 m above sea level—over 2,500 m above the lake. Mossy cliffs crowned with ponderosa pine and Douglas fir lean hundreds of feet over black water, while glacier-fed streams carve their way through steep rainforest valleys—a wild landscape that has attracted inhabitants with a spirit to match.

Home of the draft dodgers

In the late 1960s a wave of talented, intelligent Americans ran for the Canadian border with the Vietnam draft snarling and nipping at their heels. Many of these folks settled in the Kootenays, providing the basis for the communal, semi-pastoral and fiercely independent nature of these remote towns. Up here at the north end of Kootenay Lake, if you are wearing clothes on a lonely pebble beach, you are the weird one.

These expats from the Lower 48, where the grizzly has been wiped out of 98 percent of its historic range, found solace and inspiration in their wilderness surroundings. Many passionately led the fight for the myriad of protected areas in the surrounding mountains—West Arm, Kokanee Glacier, Goat Range, Kianuko, Stagleap, Bugaboo, Purcell Wilderness and a host of smaller provincial parks—that help to make Kootenay Lake one of the last, best freshwater wilderness paddling destinations on the planet. All that with access to a cappuccino and a gourmet restaurant meal, if that’s what suits your fancy.

Trip itinerary for Kootenay Lake

If you have at least four days to explore Kootenay Lake, this route from Creston to Crawford Bay offers a little bit of everything the region is famous for. Start with a mandatory tour of the Columbia Brewery (home of the world-famous Kokanee glacier beer) in Creston, put in at the southern tip of Kootenay Lake, stop for a day to enjoy hiking among old growth forests and mountain ridges, then explore the communities of the east shore before paddling or shuttling back to your car.

Day 1

To reach the put-in at the Duck Lake dike, head west from Creston on Highway #3 across the Kootenay Valley. Head North on Lower Wyndell Road (you will need to turn left and go under an overpass). At kilometer 6.9, head left on Duck Lake Road for another 6.8 km. A lovely opening allows access to the East Channel of the Kootenay. From here paddle south (upstream) for 200 m to enter the current of the main river channel.

This first day of leisurely paddling carries you under the old railway lift bridge and out onto the Dark Queen herself. The nicest paddling, and camping, is along the west shore. Several small beaches provide camping, but the nicest spot by far is the sandy beaches of Next Creek—a B.C. Forest Service Recreation site with pit toilets and picnic tables.

Boats & Guides

Kaslo Kayaking (Kaslo)

Nelson Paddleboard & Kayak Rentals (Nelson)

Inner Journeys

Yasodhara Ashram (Crawford Bay)

Environmental Info

Wildsight

Visitor’s Info

Kootenay Lake Chamber of Commerce

Parks & Camping

BC Parks

Day 2

On the point north of Next Creek, look for pictograms left by the Ktunaxa First Nations over millennia. The 230-hectare Midge Creek Provincial Park has more than a kilometer of white-sand beach. Maintained tent sites here are available for $5 per person per night.

To go for a hike on Day 3, base yourself here for two nights. Alternately, head several kilometers north to Drewry Point Provincial Park for more spectacular, and free, camping. Both these parks are boat-access only, with pit toilets and wilderness campsites that are available on a first-come basis.

Day 3

For a day of hiking from Midge Creek, follow an old, overgrown mineral exploration road up the north bank of the creek through spectacular old growth ponderosa pine. For views down the lake, follow an obvious ridge upwards to the north, 1.6 km upstream. This ridge is crisscrossed by numerous game trails and offers a mix of dreadfully thick vegetation and lovely open rambling. Rugged, exceptionally committed hikers might make it 11 km upstream along the old road to find some of the finest original cedar and spruce old-growth forest left on Kootenay Lake. Cedars in this stand were saplings when Leif Ericson landed in North America in AD 1,000.

Note: past the end of the old road this route follows many old game trails and involves some route-finding and creek-crossing skills—not recommended for a leisurely sashay on a lazy afternoon.

Day 4

From Midge Creek or Drewry Point, cross the lake to explore the east shore communities of Twin Bays, Boswell, proudly metric-free Gray Creek, and Crawford Bay. Crawford Bay has a world-renowned collection of artisans and craftsmen—from glass blowers and ironsmiths to potters, weavers and broom-makers. Nearby, Yasodhara Ashram offers introspection in a stunning setting.

There are many camping options along the shore between Boswell and Gray Creek, and also a nice spot called Steep Beach on the west-facing shore of Pilot Point. At the end of your explorations, shuttle back to your vehicle—or hitchhike, an illegal yet thriving form of public transport in the Kootenays.

This article originally appeared in Adventure Kayak‘s Summer 2007 issue. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine’s print and digital editions here, or browse the archives here.

Dave Quinn is a freelance writer, photographer and guide based in Kimberley, B.C.

The Dark Queen’s throne room. | Photo: Dave Quinn

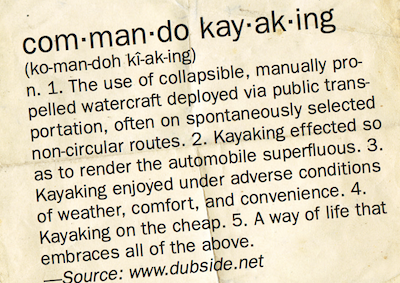

Dubside’s lifestyle package began in Philadelphia. Into the reggae scene, which incidentally inspired his famed dreadlocks, he worked as a sound engineer for bands. Living inexpensively in a single room in a house with a shared bathroom, no outside yard space, no car, no vices, he found he needed to work no more than two or three days a week to cover his expenses. Valuing time over money, for most of each week he was free. In 1998 he discovered kayaking.

Dubside’s lifestyle package began in Philadelphia. Into the reggae scene, which incidentally inspired his famed dreadlocks, he worked as a sound engineer for bands. Living inexpensively in a single room in a house with a shared bathroom, no outside yard space, no car, no vices, he found he needed to work no more than two or three days a week to cover his expenses. Valuing time over money, for most of each week he was free. In 1998 he discovered kayaking. This article first appeared in the Summer 2007 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Summer 2007 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

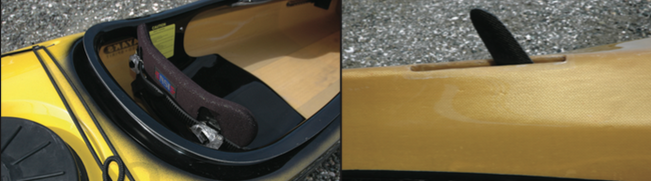

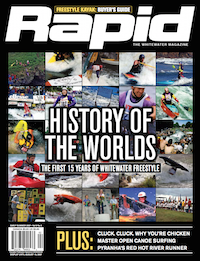

This article first appeared in the Summer 2007 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great boat reviews, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Summer 2007 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great boat reviews, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

SUPERNATURALLY COMFORTABLE

SUPERNATURALLY COMFORTABLE

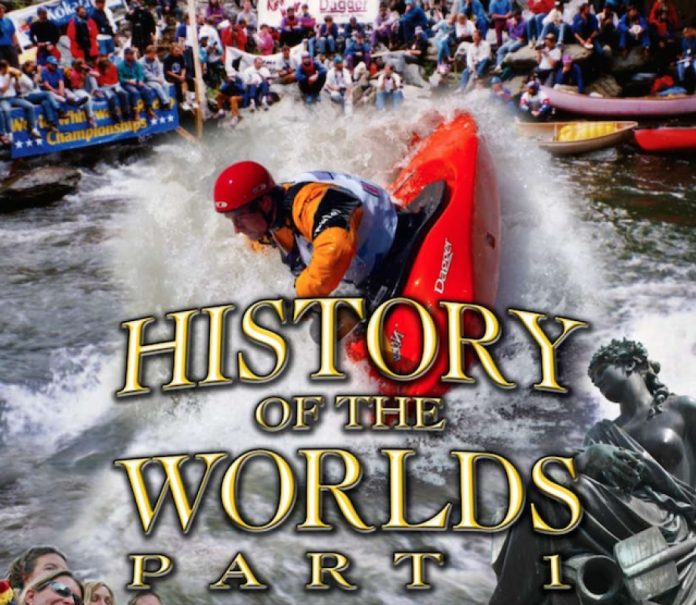

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2007 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2007 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions