I discovered sea kayaking when I was five months pregnant and not quite 29 years old. I

was watching a sunset at Flamingo Campground in the Florida Everglades. The sun was framed by silhouetted palm trees and diving pelicans splashing into the bay with wings folded back. Then I saw a sleek kayak glide peacefully into the scene. This first impression stayed in my mind, growing like a well-watered seed until, many years later, kayaking came to define my life.

I waited one and a half years after the birth of my daughter before taking my first kayak journey, a guided trip on Georgian Bay – I couldn’t leave a newborn and the demands of motherhood preceded all other notions. It took only a few strokes to realize that kayaking would become a significant part of my life. I felt I belonged on the water.

From then on, I made short kayak trips with guided groups to exotic places for a week once or twice a year. I paddled the barrier reef off the shore of Belize. I camped and kayaked along the Exumas, a chain of islands in

the Bahamas. And I paddled among icebergs in east Greenland.

These short breaks renewed my spirit and whet my appetite. I studied maps and dreamed of far-away paddling destinations, but I had parental obligations and these dreams simmered in my active imagination.

Eventually, I bought a used kayak from a tour company and I paddled

at The Pinery, a provincial park on Lake Huron. The Pinery had been my special place since early childhood, but now I enjoyed the dunes and beach from a new perspective. I was attuned to the subtle differences in the quality of light, in the clouds in the sky, in the changing of the seasons.

On the water I felt alive. My senses awakened to the rush of wind or the sting of icy water. I revelled in the songs of loons and the flight of bald eagles. My spirituality strengthened as I felt my small place in this complex but beautiful world, connected to all that exists.

AQUA THERAPY

Kayaking was my aqua therapy, a means to wash away the stresses of daily life, to get away from the continuous demands that society places upon us, or that we allow society to place upon us.

I built my confidence by paddling in varied conditions in all seasons

and in many places. I read about kayaking. I took courses and paddled with strong paddlers to strengthen my skills.

As much as I enjoyed paddling with others, I found it easiest to paddle

on my own. It meant I could paddle wherever and whenever I wanted. I relied only on myself and felt a deeper sense of being on the water. My focus was on my surroundings, not on my partners. My days as an elementary school teacher working with 150 kids a day are busy enough that I fervently seek these moments of solitude.

In 2003, in the Westfjords of Iceland, I met a remarkable woman.

Shawna Franklin was paddling around Iceland with two male partners. Her energy, vitality and genuine love for the world shone brightly. She looked at me and spoke of living true to myself.

This was an epiphany. Up until then, I had always done things to please others. I had followed the “system”, getting a university degree and a good job, getting married and raising a family, taking on a hefty mortgage. Yet it was my brief forays into nature by kayak that truly made me feel joyful and alive.

I was also inspired by a poem, The Invitation by Oriah Mountain Dreamer, which says “dare to dream

of meeting your heart’s longing” and “risk looking like a fool for love, for your dream, for the adventure of being alive.” This reiterated what I already knew but had been afraid to do for so long: to live true to my soul, which sang of being free on the water, to follow my dreams and find peace and fulfillment.

And so I found the courage to plan bigger challenges. In 2004, I paddled around Manitoulin Island, the world’s largest freshwater island. Geographical extremes appeal to me as do islands that have their own unique identities, and Manitoulin lies at the northern tip of Lake Huron. I paddled the 350 kilometres in 12 days.

A WHOLE SUMMER TO PADDLE

In 2005, I took a leave of absence from teaching during the months of May and June, giving me the whole summer to paddle. I chose to circumnavigate Prince Edward Island.

Again, it was a geographical extreme as it was the only province that I could completely circumnavigate. I was the first woman to complete the entire 600-kilometre circumnavigation, paddling it in 15 days. I then felt I could accomplish anything I put my mind to.

The following summer, I again took the months of May and June

off work, this time to paddle around Newfoundland, a demanding journey of almost 3,000 kilometres. Again I would be the first woman to do so.

I started my journey with much trepidation on a cold, wet, dreary and windy day early in May. What had I gotten myself into? I felt relieved to be paddling part of the south shore with another accomplished female sea kayaker, Freya Hoffmeister from Germany. She helped give me the strength and courage to complete the remainder of the journey alone.

I often dug to the depths of my core to face wind, waves, fog, lightning,

and long open water crossings of enormous bays. At times I felt utterly alone on such a vast and unforgiving ocean and often arrived humbled on shore, relieved to set foot on solid ground. Many days I spent eight, nine to paddle in exotic destinations and or even 10 hours in my kayak before share my experiences as a presenter at finding a landing place.

I arrived safe at Isle Aux Morts at the exact dock where I’d started 104 days earlier. I averaged 40 kilometres a day on the 68 days I paddled. Succeeding on these expeditions has meant sponsorships, the chance to paddle in exotic destinations and share my experiences as a presenter at symposiums around the world. I have even taken this whole year off teaching to continue kayaking full time.

KAYAKING AS A SELFISH INDULGENCE

These rewards have come at a price. My spirit is renewed, my zest for life continues to grow, but indulging my needs is in many ways selfish.

I have had to leave my family, who are non-paddlers, for extended periods. It has created enormous friction in my personal life when loved ones cannot fully understand my need to reach for these extended journeys at the cost of being home and making money. Because kayaking distant shores requires financial security and extended time off, I am still dependent on a job that is draining my life energy. Having sponsors also brings obligations. Some of the spontaneity of quietly travelling is taken away with the continual need to blog about my experiences and give up my privacy.

But I will continue to seek kayaking adventures. It is what fulfills me and

makes me happy. And I enjoy sharing my experiences with others. My perspective of looking from the outside towards the inside is so different from the experiences of most. Maybe I can inspire someone to grow by stepping outside of their comfort zone. It is important to keep growing as a person throughout life’s journey. The motto on

my blog states, “Make the journey of life a beautiful adventure.” Think of a dream and then visualize how you can make it happen. I am a petite, middle-aged woman. It is through sheer passion and strength of mind that I make my dreams into reality.

For years and years I devoured accounts of personal triumphs in adventure and dreamed that I too could follow my dreams. Finally, in mid-life, I reached for my dreams, realizing that time lost is irreplaceable. I feel that if you can dream it, you can do it. Achieving new personal limits has taught me that the only limits set upon ourselves are made by ourselves, in our minds.

Wendy Killoran lives and works in London, Ontario. She presents at sea kayaking symposiums worldwide and blogs at kayakwendy.com.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

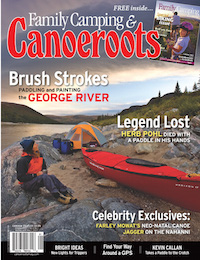

This article first appeared in the Spring 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2007 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2007 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions