Wildlife photographers are often envisioned dressed in camouflage suits, spending countless hours stalking big game and carrying monster 12-pound lenses. Not so for kayakers who photograph wildlife. As a paddler your secret weapon is not a 600 mm lens, it’s your boat. Your kayak allows you to move silently and approach animals from the water, the side where they least expect a threat. You can get much closer to animals than you can from land, and often a standard 80–200 mm zoom lens is more than adequate.

Given that many mammals, amphibians and water- fowl spend a great deal of time in or around rivers and lakes, paddlers have unique opportunities to get great wildlife shots. So get up before the sun, get out in that secret weapon, and be prepared to grab some great wildlife shots sans the camouflage suit.

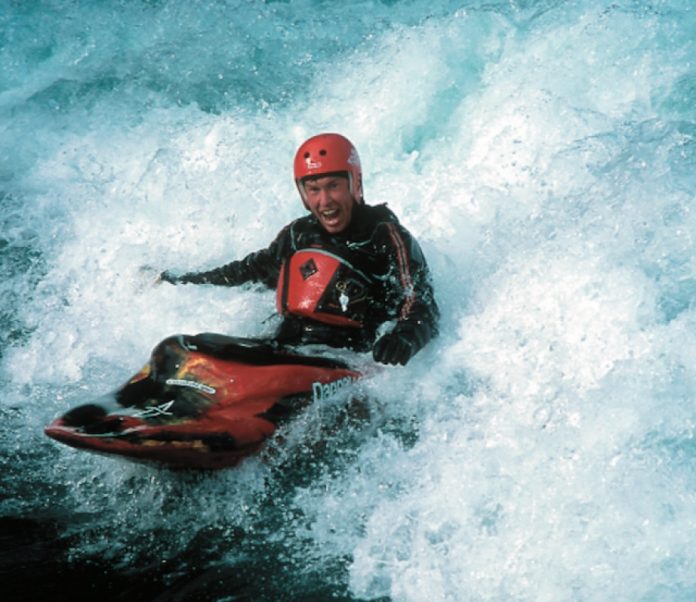

Capture movement

You’ll often want to use a high shutter speed to reduce blurring when shooting from a moving platform. Try not to get locked into static wildlife portraits, however. Experiment with shutter speeds and panning effects to illustrate motion. Kayaking the coastline of Alaska close to Cordova, we came upon a huge flock of gulls feeding on a school of small fish. Initially I shot at a fast shutter speed. Gradually I slowed it down to 1/15 to 1/30 of a second. This captured the movement and chaos of the feeding frenzy.

Getting close to wildlife

To get close to wildlife, I use quiet paddle strokes and a dark-coloured paddle—a white paddle blade will alert an animal much more quickly. Paddle upwind if possible to avoid the animal catching your scent. And paddle close to the shoreline and be ready to shoot when coming around bends or into open areas in reed beds. While exploring the wetlands and creeks of Riding Mountain National Park in Manitoba, we heard a loud splash and came around a bend to see a young moose going for a swim. We followed at a safe distance for several minutes and I was able to fire off two or three frames before he loped off into the bush. The huge cloud of insects may explain why he stayed in the water for so long.

Use fill flash for bright backgrounds

Along the California coast near San Simeon, we came upon a herd of elephant seals sunning and trying to attract the attention of the females. When paddling, I try to keep the light coming from behind, over my shoulder, but this isn’t always possible. I use the fill flash to offset the bright surf behind and bring out some detail. Using the flash to enhance what might be your only good shot has to be weighed against the chance of scaring off the animal.

The early bird gets the shot

Getting up early in the mornings or taking an early evening paddle will increase your chances to see wildlife. Use 200–400 speed film to shoot in the low light. On one early morning paddle I was able to closely approach a small group of deer near our campsite on Maligne Lake in Jasper National Park, Alberta. Drifting very quietly, I waited until the doe peeked out from behind a tree before firing off three frames. The third one was the only sharp one. For sharper images when shooting from a stable kayak, try using a monopod resting on the floor of the boat and brace the camera against your forehead.

Use fill flash for catch light

Getting out of the boat and wading in the tidal pools at low tide is a great way to discover starfish and other kinds of marine life. In the early evening on the Pacific shoreline near Morro Bay, California, I was able to get quite close to a snowy egret while he was focused on catching supper. Fill flash really helps to bring out detail in eyes and feathers especially in birds with black eyes and dark feathers. If you are shooting skyward at flying birds, use a flash to fill in the shadows underneath.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2003 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2003 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2003 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2003 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2003 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Summer 2003 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions