The online classified’s glorified details set my dreams in motion: a couple hundred bucks for a 15.5-foot, slender solo tripping canoe; 45 pounds of fiberglass adorned with ash trim. Just the ticket for independent trips on sprawling lakes and placid rivers. I mailed the seller a check sight-unseen and had a friend deliver the canoe to me a few weeks later.

“It’s a little rough,” my friend James reported, as we carefully lifted the canoe off the roof of his SUV. Only a skilled carpenter like James would so rashly understate the deplorable condition of my new canoe. Its weatherworn, desert tan hull was webbed with spidery cracks, the worst of which were coated in ugly, snot smears of epoxy. Rotted gunwales were spongy to the touch. After a few short outings where I observed steady streams of river water infiltrating the hull, the canoe—and my dreams—were shelved and almost forgotten.

But here’s the thing with a once-pretty canoe: It can’t help but catch your eye. A year later, when common sense still urged me to look the other way, the canoe spoke to me. Its sparsely upturned stem and stern screamed speed across open water, and its graceful tumblehome cried the promise of thousands of efficient, comfortable strokes. I caressed its fractured chines and conceived of a rehabilitation plan involving orbital sanders, fiberglass cloth, polyester resin and gelcoat. I would grind, glue and paint life into this aged spectre, and celebrate its rebirth with an autumn trip.

Putting my priorities in order, I thoroughly researched and planned a 70-kilometer lake circuit months before I set about rebuilding the canoe in which I would do it. When I finally chose a late-August heat wave to begin the restoration, it quickly became apparent that my old electric sander was no match for the canoe’s craggy skin, so I borrowed a friend’s stone-wheeled angle grinder. The grinder fervently tore into the job, creating clouds of caustic dust and ripping holes in the rotted fiberglass.

In 30 minutes of hot and dirty work I managed to obliterate most of the cracks. The result was a heinously holey, splotchy and morale- crushing canoe. I threatened to dump it in a landfill or, better yet, scuttle it with a final rock-bashing run down my local class III river.

Here’s the thing with a once-pretty canoe: it can’t help but catch your eye

Unwilling to accept defeat, I summoned visions of gliding across steaming lakes rimmed with fiery forest and silent stone. Intent on the objective, I laid strips of resin-saturated fiberglass cloth along the inside of the canoe wherever I had gored the exterior. Then I sealed the hull with gobs of milky gelcoat, and chopped out and replaced the punkiest pieces of gunwale.

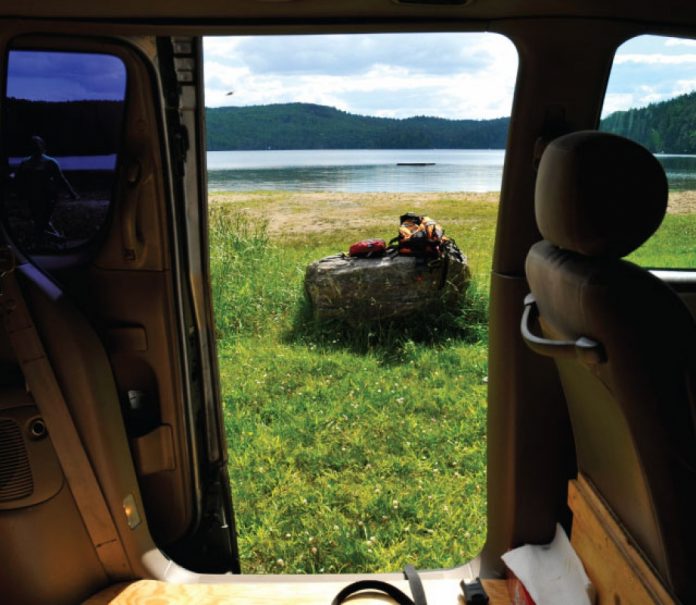

Figuring it would be wise to travel in the company of a capacious tandem on my solo’s maiden voyage, I recruited my wife Kim and friend Brad to come along. Kim, who’d been privy to all the peaks and valleys of the reclamation debacle, expressed her doubts when sunlight shone through the clear-coated hull as we affixed it to my truck’s racks. “But think of how fast we’ll travel three to a canoe,” she teased.

Shoving off from a sand beach on Lake Wanapitei, kneeling amidships, I gradually heeled the gunwale closer and closer to the water, growing accustomed to the tender stability. Bow pierced morning mist, trees burned with color and, amazingly, the canoe remained dry. For the next five days, canoe and I followed a J stroke course across the lakes, rivers and streams of my dreams.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2011 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.