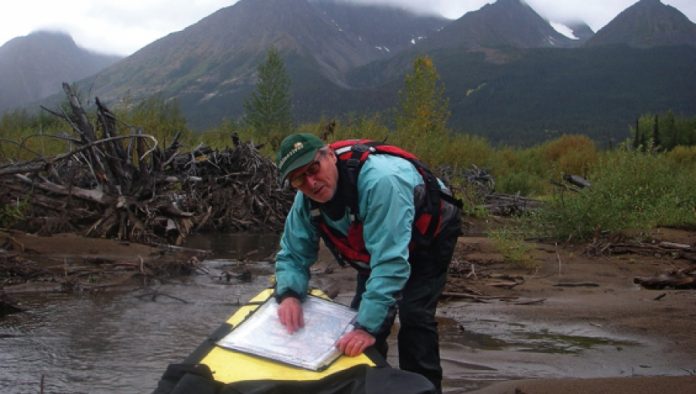

I’ve long used the jet ferry as a reliable method for crossing wide expanses of current, or reaching mid-river surf waves. But the incredible speed and efficiency of this move wasn’t fully revealed to me until last summer.

Paul Mason and I were teaching out West on Alberta’s Red Deer River and were impressed with the many spectacular surf waves. Front surfing, back surfing, spinning on waves—on this river you could do it all! Paul commented curiously on the remarkable speed of his jet ferries. Could it be that there was something different about these waves compared to ours back east, or was there something different about Paul? (Some of you may know the answer already if you’ve read his Bubble Street cartoons.)

To solve the mystery, I watched Paul and others tackle some challenging jet ferries. Most kept an active paddle or ruddered throughout their move. But not Paul. He kept his paddle vertical, practically side slipping on a draw. When I asked him to rudder instead, he claimed the magic was gone and the surf felt slower. It turns out that the secret to Paul’s accelerating jet ferry is to use the paddle blade as a foil to sail across the wave. When he ruddered, the blade no longer had the foil effect, making the move feel sluggish in comparison.

To understand how this works, imagine a miniature sailboat upside down on a jet ferry wave. The inverted boat would have its sail catching the current instead of the wind. A paddle blade acts in much the same way. Just as with a sail, a paddle catches the rushing current and redirects it behind you toward the stern of the canoe. With the water deflected to the stern, the paddle is propelled forward increasing the speed of a jet ferry—just like a sailboat tacking across the water on a windy day.

Similar, too, is how the hull of a sailboat or canoe tracks the boat to prevent sideways movement. A sailboat needs a keel to grip the water so that the force of the wind will move the boat forward. A canoe uses its chine in the same way. The edge of the canoe carves aggressively into the wave face—that plus gravity pulling the canoe down the wave keeps the canoe on a forward path so it doesn’t slide downstream and off the wave.

To gain the most momentum from the paddle sail, angle the blade so that the leading edge points slightly in the direction of the ferry. Similarly, point the canoe across the wave but with just enough upstream angle to cause it to surf down the wave face. For sailing, the best jet ferry waves are ones positioned perpendicular to the flow of the current.

Mystery solved. As it turns out, Paul is different, at least in how he jet ferries.

Andrew Westwood is an open canoe instructor at the Madawaska Kanu Centre, member of Team Esquif and author of The Essential Guide to Canoeing. www.westwoodoutdoors.ca.

This article originally appeared in Rapid, Spring 2012. Download our free iPad/iPhone/iPod Touch App or Android App or read it here.