Put simply, a crossing occurs anytime you cannot safely return to land virtually instantaneously. This includes shortcutting across the mouths of bays or fiords, island hopping and paddling around cliffs or rocky capes where you may be close to shore but still vulnerable with no safe exit.

There are three dangers inherent in any crossing: general fatigue, capsizing and drifting off course.

When Dr. Hannes Lindemann prepared for his solo kayak crossing of the Atlantic in 1957, he trained to stay awake and alert for long periods of time. Fatigue can affect judgment and decision-making ability as well as paddling ability.

To gauge your personal limits, start with short crossings and gradually work your way towards covering longer distances. You’ll find strength and joy as you tickle the borders of exhaustion, but don’t get halfway out on a 20-mile crossing and realize that it’s too much.

Kayaking books teach techniques for getting back in your boat after you’ve capsized. The best advice: Don’t tip over in the first place. Practice bracing and righting skills in rivers or surf—any place with complex hydraulics. If you don’t enjoy the chaos of rough water, limit your exposure to crossings. As with training for fatigue, match your risk to your skill level and personality, leaving leeway for the situation to become more intense than you initially envisioned.

In order to avoid drifting off course, careful calculation and planning for a number of scenarios are necessary.

Catabatic winds can occur any time high, cold peaks border warmer shorelines. Cool air may spill down the mountains, creating intense offshore winds that can push you off course.

They usually intensify in the afternoons, so plan accordingly.

Tidal currents are most intense where there is a large tidal range and where narrow straits connect two bodies of water of different sizes and depths. For example, tides would race through a channel connecting a shallow bay and the ocean, creating shears and eddies where speeding water interacts with calmer water. To avoid the impacts of tidal currents, travel at slack tide or take potential drift into consideration.

The most exciting crossings involve passages to small islands where, if you miscalculate, you may find yourself adrift on the open sea. Deepsea waves, winds and currents require that you study pilot charts, talk to local sailors and fishermen, and always err on the upwind side. It’s much easier to drift downwind at the end of a long day than to battle against wind or current in the fading light.

When taking on a crossing, be sure to bring lots of food and water, and have your navigation gear and extra clothes in an easily accessible, waterproof deck bag.

Jon Turk’s book, In the Wake of the Jomon, chronicles his two-year crossing from Japan to Alaska.

This article originally appeared in Adventure Kayak, Spring 2011. Download our freeiPad/iPhone/iPod Touch App or Android App or read it here.

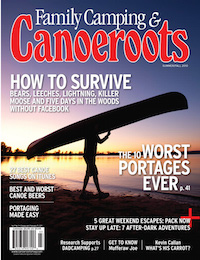

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2010 issue of Canoeroots.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2010 issue of Canoeroots.

This article first appeared in the Summer/Fall 2010 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Summer/Fall 2010 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions