This profile originally appeared in Rapid magazine.

Every cloud has a silver lining. Even if that cloud is a powerful, global sports brand suing your struggling start-up for trademark infringement. In the case of Steve O’Meara, the shimmer within the storm was Kokatat.

When the natural resources student from San Francisco’s Bay area arrived in the small coastal community of Arcata, California, to attend Humboldt State University in the late 1960s, he knew he’d found a special place. The keen outdoorsman could spend his free time kayaking northern California’s wild coast and rivers, trekking among the redwoods or climbing in the nearby Klamath Mountains and Coast Ranges.

When he graduated in 1971, O’Meara found the only thing lacking in Arcata was prospective employment. Determined to stay, the enterprising 23-year-old scraped together the capital to start a small outdoor equipment retail store catering to backpackers and cyclists. It wasn’t long before he discovered that the products he wanted to sell simply weren’t available. Recognizing a need, O’Meara plunged ahead with blind optimism.

“I didn’t have much business background and I definitely didn’t have any production background,” he recalls, “how to make the stuff was learned on the fly.”

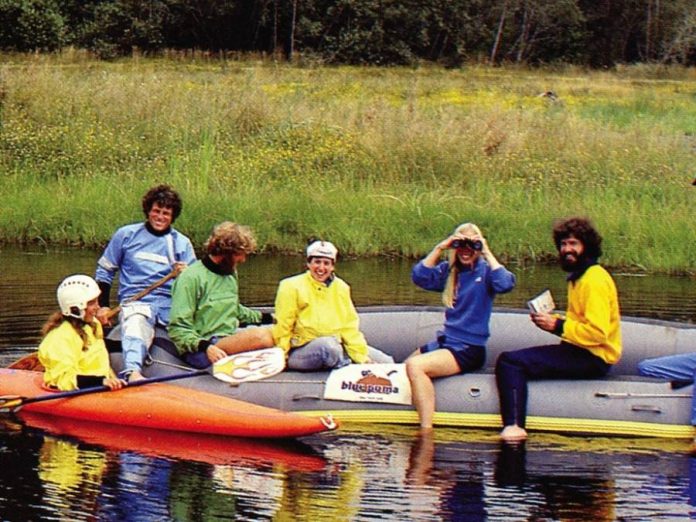

With his then-business partner Chuck Kennedy, O’Meara purchased a couple sewing machines, started scrounging raw materials from local suppliers and branded his new company Blue Puma. Operating out of the back of their retail store, O’Meara and Kennedy manufactured high-end, made-to-order down sleeping bags, parkas and bivy sacs.

In 1976, the men were among the very first in the outdoor industry to recognize the potential applications of a new waterproof/breathable fabric called Gore-Tex. A bivy sac crafted from the material brought Blue Puma national recognition.

In 1980, O’Meara’s friends Don Banducci and Rob Lesser asked him to create paddling clothing for their upcoming expedition on the Alsek River in the Yukon/Alaska.

“We developed a very basic paddling jacket with a neoprene cuff and some fleece under garments—it’s sort of laughable now,” remembers O’Meara. Nevertheless, says Lesser, the Alsek paddling jackets were superior to the wool and flimsy nylon paddling clothes of the period.

Blue Puma was gathering momentum. Then, in 1986, O’Meara received a letter from Puma shoe company alleging trademark violations. Without the money to fight the charges, he was forced to change the name.

Re-branding the company offered O’Meara the opportunity to narrow his focus. “I decided I’d rather be a bigger fish in the small pool of watersports,” he summarizes.

A friend suggested the name Kokatat. Meaning “into the water” in the language of the indigenous Klamath River people, the new name fit perfectly with O’Meara’s commitment to paddlesports and keeping production in Arcata.

Even with a clear purpose and a fresh name, Kokatat almost ceased to exist. Struggling to secure financing, turn a profit and weather stiff competition from new rivals like Stohlquist, O’Meara put his company up for sale. “The offer I got was kind of insulting, so I decided I had to turn the company around,” he says.

Kokatat’s success hinged on recognizing paddlers’ needs and figuring out innovative ways of satisfying them. In 1986, Kokatat created the industry’s first paddling drysuit. Gore-Tex and advanced laminates and treatments followed.

O’Meara also recognized the importance of credibility and product feedback generated through sponsoring professional paddlers. Since the Alsek expedition, Kokatat has signed no fewer than four World Champions and outfitted the U.S. Olympic team.

O’Meara credits Kokatat’s popularity with professional athletes to a tradition of function-first designs. For their part, Team Kokatat’s international ambassadors have helped transform utilitarian function—and mango onesies—into paddling haute fashion.

For both longevity and ethics, O’Meara is admired throughout paddlesports. “Steve is an ex- ample of the entrepreneurial rocks upon which the whitewater industry worldwide was built,” says Lesser. “He never [sold] out to the consolidators of this industry. I couldn’t speak more highly of his manufacturing philosophies.”

After four decades, O’Meara is still enjoying the daily challenges and rewards.

“Kokatat changes about every five years so it’s endlessly interesting for me,” he says. “People ask how I can do the same thing for 40 years and I tell them, ‘I don’t.’”

This article originally appeared in Rapid, Early Summer 2010. Download our free iPad/iPhone/iPod Touch App or Android App or read it here.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions

Master the Traditional Stroke

Master the Traditional Stroke