Publishers often send us new kayaking books to review. When I got Jon Bowermaster’s latest from National Geographic, Descending the Dragon: My Journey Down the Coast of Vietnam, I was struck by something very odd. I counted 78 photographs between the covers, exactly six of which showed any sign of the paddlers or their kayaks. That’s less than eight per cent of the images in a kayaking book having anything to do with kayaking. What’s going on?

The late photographer Galen Rowell wrote about a concept called “image maturity.” He said that when a subject is new to the audience, you offer them the photographic equivalent of a two-by-four to the head— obvious photos that are a direct depiction of the subject. In Rowell’s example, the popular photo for stories about Nepal trekking in the 1980s was a portrait of a Sherpa. In recent years, editors passed over that image for ones that they previously thought “too subtle.” As trekking became more familiar, the maturing audience got the same message out of increasingly abstract pictures while the old images became ho-hum.

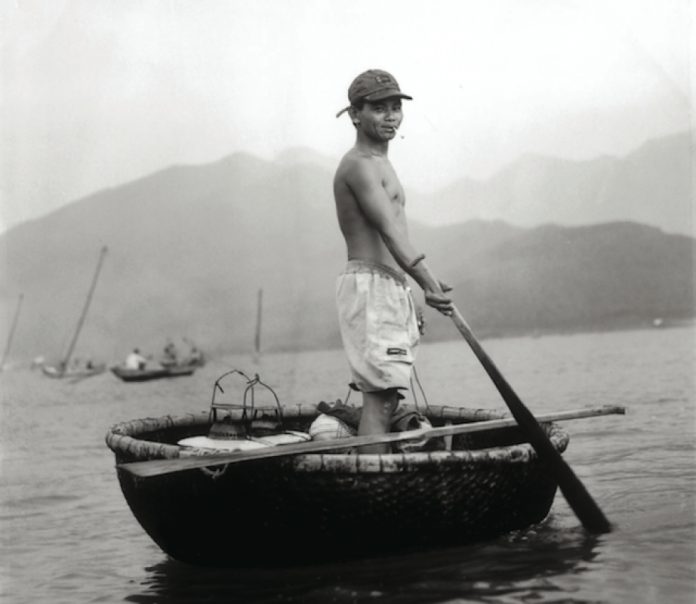

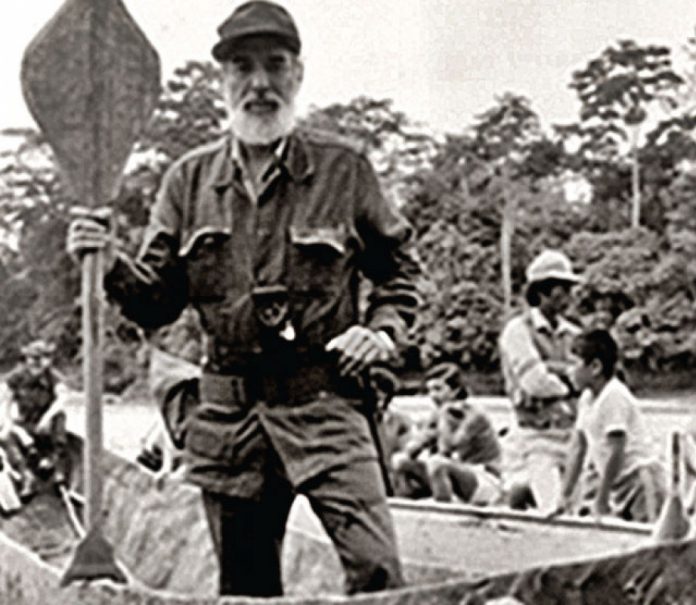

By this definition, Rob Howard’s photos in the Vietnam book are very mature. Like the one printed above, they are pictures of the world Bowermaster’s team saw from the seats of their kayaks. Images of fishermen, streetside merchants, bicycles, fishing nets, floating villages, rowboats, bamboo boats, dogs, schoolgirls, war memorials, Buddhist monks, sandals, cows, jellyfish and pagodas. Images far more diverse and informa- tive than the so-called lifestyle photos in a kayaking magazine.

In Rowells term’s, this magazine has some growing up to do. Eighty per cent of the photographs in a typical issue of Adventure Kayak include kayaks. Rowell points out that image maturity is audience-dependent. Meaning that a subject’s enthusiasts, like the readers of a kayaking magazine, should be the most sophisticated audience—in theory the quickest to be turned off by a visual cliché. And yet we usually just bonk readers on the head with pictures of kayaks.

But I’m not just talking about photos. Bowermaster’s text, too, focuses on the people, the politics and the culture of Vietnam, not the usual trip details of paddling, eating and weather. Bowermaster sees himself as a journalist first and a paddler second. He calls kayaks floating ambassadors. They’re a tool to see a place and meet its people.

I emailed Bowermaster with this observation and he replied, “I’m glad you got the message.” The message is a whole philosophy of travel, a way of being and seeing.

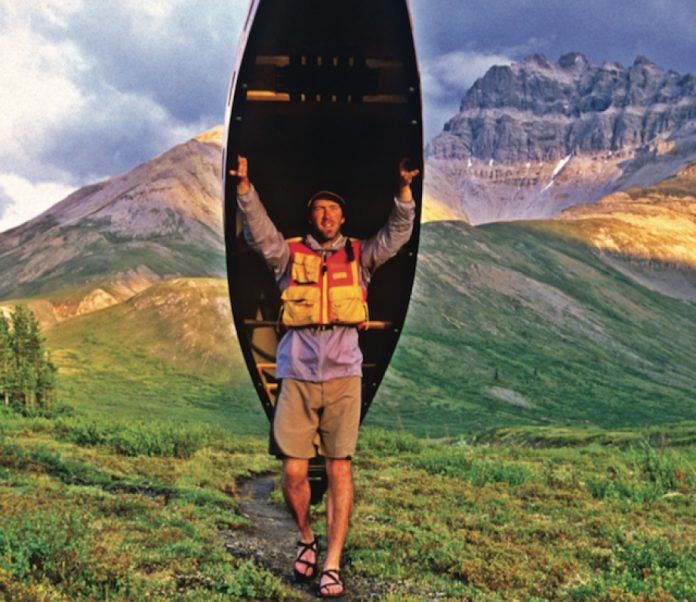

I’ll bet that many of you who read this magazine paddle for some other purpose—to fish, to bird-watch, to be at one with water and nature—and I hope we can speak to that motivation in pictures and in words, celebrating the world you see from your kayaks. Go kayaking. Lift your eyes from the cockpit and take a look around. It’s beautiful out there.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2009 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2009 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2009 issue of Adventure Kayak magazine. For more boat reviews, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2009 issue of Adventure Kayak magazine. For more boat reviews, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Fall 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Fall 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions