The weather absolutely sucked: torrential rain, skyscraper waterspouts blasting across the inlet, the nearest lighthouse reporting hurricane force gusts. The wind steam-rolled our kayaks down the beach and filled our cockpits with sand. It was so awful that I took out my waterproof camera and snapped a photo, the one printed above. You could’ve almost bet that it would never appear in a magazine.

you don’t see this side of kayaking in our photos very often. In so many places where we paddle, we spend days upon days en- cased in clammy nylon, yet the cliché is the blue-skied slide show that makes everyone say, “You had such beautiful weather!”

To collect photographs is to collect the world, writes susan sontag. and we like to collect beautiful things. “Rain, rain, go away,” we say, and you can see it in our snapshots. Magazines have more fashion photos of sexy beauties and more travel photos of sunny days.

TAKING THE BAD WITH THE GOOD

There’s another reason we have so many fair-weather photos. It’s not just because nobody wants to get their camera wet. It’s because we kayakers can see blue skies and sunsets as what they really are to us—rare moments well earned. We remember the time the sun came out after 72 hours of rain, how good it felt to leave the tent and not get our clothes pasted to our skin. Those are some of our happiest moments. We photograph them because, as the writer Eudora Welty observed, “a good snapshot stops a moment from running away.”

Fair enough. But there’s a risk that every golden image hides the soggy truth that you’ve got to take the bad with the good.

As a skier, I have a theory about bad snow days that also applies to rainy paddling days. I think it’s a numbers game. The more crap days you endure, the more priceless pearls you find. You’ve just got to put in the time.

I don’t ever want to forget that yin and yang, like when I go camping again after months indoors and experience the shock of discomfort: “hey, it’s cold out here. It’s wet, the ground is hard, there are bugs. Why am I here?” I’ll bet it’s just this temptation to flee to the nearest holiday Inn when it dumps on day 1 that turns most people off wilderness, which is too bad because the outdoors needs all the friends it can get.

Next time you’re out in a gale, snap a few photos so you remember the whole story.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2007 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2007 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

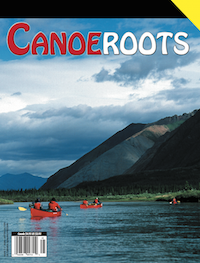

This article first appeared in the Summer 2004 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Summer 2004 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions