The generation that created the river industry, and much of paddling as we know it today, is greying. After 30 some years and the switch from canvas packs to barrels, retirement is just around the next bend. As the paddling guide industry faces the end of an era, I thought we should look back—something we’re just too young to have done before.

Mountaineers can point to 1899 when the Canadian Pacific Railroad hired two Swiss mountain guides to operate out of its glacier house hotel, starting a long and distinguished tradition of recreational mountain travel. Rivers, on the other hand, have been travelled since the beginning.

For several hundred years first nation guides were the cornerstone of European exploration of the continent. Voyageur guides picked up where they left off by driving the fur trade up and down the waterways, to be replaced by logging’s river drive foremen. guides yes, but the purpose was cartography, furs and lumber, not recreation as we know commercial river guiding today.

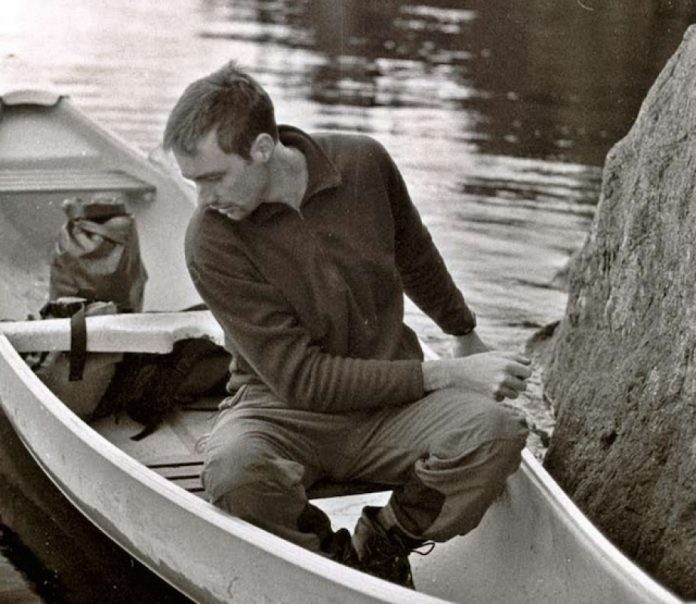

Rather than being born, recreational river guiding spawned and hatched slowly. sometime in the 1800s fishing guides, relying on the canoe, began tak- ing paying clients into the wilderness. At the same time, summer canoe camps came into existence, building their programs around canoe tripping and skilled trip leaders. simultaneously the opening of the west’s rivers, such as the colora- do, created an enamoured public and capable boatmen looking for post-exploration employment. Across the continent scruffily bearded, young adventurers started scratching out a living by guiding others down rivers.

By the late 1960s and early ’70s, buoyed by summer canoe camp graduates, advancing gear, huge numbers of then-young baby boomers and an emerging environmental awareness, canoe outfitters and whitewater rafting businesses sprang up everywhere. they grew from backyard sheds into what is now substantial business—adventure tourism.

Operating Black Feather out of his mother’s basement, in 1971 wally schaber was on the leading edge of river-based adventure tourism. Then, $700 would get you several weeks on the nahanni, where schaber was the first licensed canoe guide. “We were cheap and there were a lot of young boomers with some skills. we offered them adventure. At the time, running whitewater was considered pretty extreme,” remembers schaber with a chuckle. Now that same Nahanni trip costs $5,500.

In retrospect the baby boom makes everything sound easy. but really, the intervening 35 years—between basements and big business—the pioneer guide services had to literally create paddling in the minds of the public. The Nahanni and Colorado rivers, if heard of at all, sounded mysterious and dangerous. whitewater rafts and kayaks were unheard of. Spending good money on a river trip as a vacation was a new idea and not an easy sell.

To survive, river guides were forced to become marketers and salesmen. It was an uncomfortable transition and many of them packed it in or went broke. Trip plans gathered dust while business plans were patched together. Trade shows replaced exploring new rivers. Getting down the rivers was the easy part, getting deposits for summer trips was the real challenge.

The business of guiding grew beyond its cottage industry roots, and with it came mainstream recognition, laws, permits, insurance and regulations. Now in their 50s and 60s the founders of the industry have seen it all develop before their very eyes—indeed driving this development, whether they liked it or not.

Although their tenure may nearly be over, many who created river guiding are still standing at trade shows signing up new clients. After all, the industry is quite literally their life’s work.

Every paddler I know is a paddler because of this history. The rivers we paddle, we can paddle because these greying pioneers and their thousands of paying clients lobbied for river conservation and preservation. The question we have to ask is, with the Baby Boomer heyday gone and the number of regulatory hoops, will anyone step up and guide us for the next 30 years?

I hope so.

Jeff Jackson is a professor of outdoor adventure at Algonquin College in Pembroke, Ontario.

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2007 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2007 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions here.

This article was first published in the Early Summer 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine and was republished in the 2023 Paddling Trip Guide.

This article was first published in the Early Summer 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine and was republished in the 2023 Paddling Trip Guide.

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions