For every sport, there are defining moments, brief seconds in time that last forever, recognizable by fans and non-fans alike. The shot heard ‘round the World, the immaculate reception, Gretzky’s 894th goal, whatever they are, these events resonate and things are a little bit different from that moment forward. We don’t have a World Series, Super Bowl or Stanley Cup. Instead we etch first descents upon whitewater’s hypothetical mantle as our greatest achievements. Sometimes first descents are more than the birth of new runs; sometimes they make us believe anything is possible.

ALEXANDREA FALLS, TWIN FALLS TERRITORIAL PARK, NORTHWEST TERRITORIES

By Neil Etienne

When Tao Berman successfully cleaned Alberta’s 98.4-foot upper Johnston Falls in 1999, the paddling community perked up. Waterfall descents have increasingly gotten higher but this one not only gave hope the century mark could be broken, it was proof a 100-foot drop was really just a matter of the right river, the right levels and the right stuff.

Although he was washed from his kayak, in 2002 Tim Gross paddled himself over Oregon’s 101-foot Abiqua Falls, setting a new limit to test. In 2003, seasoned waterfall runner and extreme steep creeker Ed Lucero serendipitously discovered Alexandra Falls and all the pieces fell into place.

Heading into the Northwest Territories for a few days of surfing on the Slave River, Lucero, then 37, was shown the first major jewel on the fabled Water- fall Route, NWT Highway 1.

“I had no idea Alexandra Falls even existed so I wasn’t heading out to break any records by any means,” Lucero explained. “Once I saw it, I almost immediately saw the perfect line. It became a crossroads for me. I went there for a week and a half and plotted out whether or not I should do it.”

Topping out at nearly 106 feet, Alexandra Falls would have been the ideal location to plummet into fame for many paddlers. Lucero saw something more; a 105.6-foot-high soapbox, the ultimate chance to make a statement. He would stand up to fear in the hopes others would too.

“We were a country living in fear. We were at war, people were afraid to live their lives. I stood there and said ‘I think I can make a statement. I think I can make this fall.’ The message was to overcome fear,” he said.

Although he too swam from his boat, the bar was reset four-and-a-half feet higher.

Lucero said he won’t look for a higher drop, but suspects waterfall running will spur on its own industry and technology, pushing the vertical limits even higher. His own experiences led to the introduction of a specially armoured PFD, Stohlquist WaterWare’s Mark 1, which he designed for the impact of waterfall drops.

“The response I got at the bottom of the falls was incredible and I think a lot of people and manufacturers are going to want to get in on that. It’s prob- ably going to take on an industry all of its own and who knows how high people will be able to go.”

As of presstime, three and a half years later, Lucero’s run on Alexandra Falls remains the highest waterfall paddled and survived.

GRAND CANYON OF THE STIKINE RIVER, BRITISH COLUMBIA

by Neil Etienne

The Stikine River carves a 700-kilometre path toward the ocean through B.C.’s rugged north country and the dangling leg of Alaska, about 240 kilometres south of the Yukon border. The tail end of a transcontinental highway for the Hudson’s Bay Company’s canoes, she fed the fur trade and the Klondike gold rush.

Her crowning glory, the Grand Canyon of the Stikine, towers sentinel over a narrow 80-kilometre stretch of vicious class V+ that even after a handful of descents, the surrounding provincial park advertises as strictly unrunnable.

When the first bridge crossed the river’s banks in the early 1970s, paddlers began to imagine the possibilities. British paddlers scouted a portion of the river in the mid-’70s and even ran the river below the canyon (mostly class III), but were unsure of the upper reaches.

Around the same time, Rob Lesser was frequently planning and running expeditions in remote rivers throughout B.C. and Alaska. The famed whitewater expedition paddler and 2005 inductee to the International Whitewater Hall of Fame was running the highway back and forth during several years in the late ‘70s from his home state of Idaho, to his park ranger job in Alaska, keeping his eyes open for prime spots. He shared a few notes with the British paddlers and started plotting in earnest.

River information was scarce; this was not the enlightened Internet age. There was some information through B.C.’s hydro company and it appeared to Lesser the gradient was reasonable, even if flows for most of the year were not.

Finally, in August 1981, an all-star cast including Lesser, Lars Holbeck, John Wasson, Rick Fernald, Don Ban- ducci and an ABC Sports television crew, complete with helicopter, slipped into the Stikine.

The levels were so intense the television crew quickly had all the glorious and jaw-dropping footage they needed, cutting the trip short and flying the paddlers to the mouth for final shots. It left a good portion of the canyon unrun.

In 1985, Lesser and Holbeck, along with Bob McDougall, did what had been building for nearly a decade and returned to make a full descent.

MEKONG RIVER, TIBET TO VIETNAM

by Kyle Dickman

Iron age farmers, Marco Polo and Maoist revolutionaries all had to accept the unbridled power that kept southeast Asia’s Mekong River un-run for millennia. It wasn’t until the eve of the 21st century the mekong’s unfettered tradition was to be challenged by well-equipped expeditionaries and the demands of a changing civilization.

en route through its seething 4,600-kilometre, source-to-sea run, the mekong pounds down 3,000- metre-deep gorges, across six national borders and between some of the world’s most biologically diverse temperate forest. It is a source of food, water, transportation, energy and frequent fear of flooding for some 60 million southeast Asians living along its banks.

Western interest in paddling the Mekong began as early as the 1600s but the first serious expedition, led by french explorer and diplomat ernest Doudart de Lagrée, wasn’t attempted until 1866. After two years of barefoot portaging (apparently portaging wooden dories is a bit rough on 19th century footwear), struggles with violent rapids and a tenacious case of amoebic dysentery, Lagrée discovered what the Chinese already suspected, the river was unnavigable.

For 130 years the frenchman’s assessment stood. In the mid-1990s, interest in the Mekong’s whitewater rekindled. Teams from China, Australia, Japan and the U.S. began probing the nether gorges of its Himalayan high-country.

After seven years of wading through Chinese bureaucracy, American rafter Peter Winn secured permits and logged a handful of first descents before Australian kayaker Michael O’Shea connected the dots to complete the first source-to-sea expedition in 2004. After seven months of enduring chilly Tibetan temperatures and swarms of multi-national mosquitoes, o’shea conquered the whitewater responsible for centuries of defeats.

Conquered, perhaps sadly, seems to be the Mekong’s destiny. In reaction to a multiplying population and a ballooning economy, China has entered a dam-building era unseen since U.S. engineers trowelled off the concrete of the Grand-Coulee and Hoover dams in the 1930s and ’40s. Already three dams have been completed on the mekong with plans for as many as 100 more.

Fortunately, in 2006 American Travis Winn, son of Peter Winn, and a handful of rafters caught one last ride—a famous final descent if you will—down a river that may not be run for another millennium.

NARROWS OF THE GREEN, ASHEVILLE AREA, NORTH CAROLINA

by Neil Etienne

A little less than 20 years ago, North Carolina’s Narrows of the Green River was nothing more than a portage route that joined the more gentle stretches upstream and down.

Long touted as unrunnable, it wasn’t until 1988 when creekers Tom Visnius and John Kennedy finally executed a full-on descent that the Green Narrows began its torrid ascent to popularity. In a few short years it became one of the most popular class IV–V+ stretches in the U.S.

Earning a first descent on the Narrows was difficult enough in a kayak, certainly no one would have any business running them in a canoe, right? Particularly when the river—controlled by dam release—could be pumping out a savage 8.5–11.33 cms, unlike modern flows, which seldom top 5.66 cms.

Dave “Psycho” Simpson stepped up to the Green’s banks with his Dagger Encore about a year after Kennedy and Vis- nius, but before word had really spread about the 11 gnarly class IV–V+ rapids in quick succession.

“It was overwhelming,” Simpson described his first meet- ing with the Narrows. “At the time I thought it was completely unfeasible to run. I thought it would be suicide.”

So, Psycho set out, bringing along trusted partners Bob McDonough and Forrest “Woody” Callaway. Over a couple of days they picked away at the rapids, only a couple of which had been named. The most beastly would earn its name on that trip—Gorilla.

“At the time it was completely uncalled for,” Simpson said. “It was unrunnable. The guidebooks said it was unrunnable, ev- eryone said it was unrunnable. Then I thought ‘Oh, the guide- books are wrong; what else could they be wrong about’.”

The Narrows would remain a favourite for Simpson as he would run it every chance he got, sometimes twice a day. It inspired him to tackle the Gauley, Tellico, Watauga and Russell Fork when its releases were far more substantial.

Simpson was not the only one inspired by his runs of the Green Narrows, they marked the beginning of OC creeking. Many single-blade paddlers began to think of the possibilities; an open boater had not only survived a steep class V, he had done so with grace.

Wayne Gentry’s Green Summer, the 1992 National Paddling Film Festival’s “Amateur Best of Show” showcased the Nar- rows and Psycho’s skills at that year’s Gauley Fest, where a young Eli Helbert, now at the forefront of open canoe creeking and the only open boater to enter the Narrows of the Green River Race, watched in awe.

“I remember thinking that guy’s crazy, I could never do that. But because Psycho did it first, a lot of us were willing to do it too when the time came,” Helbert says. “When I saw the movie I knew I had to try.”

OTTAWA RIVER, BEACHBURG ONTARIO

by Neil Etienne

There are few rivers in Canada that compare historically with the Ottawa. It’s a river that built a country, yet it was forgotten or at the very least overlooked, as a paddling industry raged on without it. How does a river that now rivals all others as the ultimate playboating, training and testing ground remain only a logging and trade route until the mid-1970s?

Simple. Lumberjacks don’t paddle and farmers don’t swim.

The Ottawa borders the TransCanada highway but the rapids lay hidden at the back of privately owned farmland where whitewater is more of a burden than boon. Local landowners saw no jewel and the whitewater remained a well-kept secret.

In June of 1974 Hermann Kerckhoff, founder of the Madawaska Kanu Centre, took his daughter Claudia to the Ottawa. he was there to disprove rumours that there was whitewater on the river.

Putting in on the Quebec side at what is now known as McCoy’s, the duo was pleased by what they saw, if only briefly.

“It was a total surprise to my dad and I to see any whitewater at all. After McCoy’s Chute it gets flat, so we still didn’t expect anything much downriver,” Claudia explains. “Then we came to a split and the river got our respect immediately.” Choosing the right path, they discovered what is now known as the Main Channel.

“It was total euphoria. we’d never seen such big or friendly whitewater,” Claudia recalls of the river that would someday be the host of two world freestyle championships. “This was the find of a lifetime.”

That summer expert paddlers from MKC began running the remaining branches and by 1975 others began to take note of the Ottawa’s potential.

Ed Coleman, an American rafting company owner and a mentor of sorts to Wilderness Tours owner Joe Kowalski, flew over the rapids that year and several weeks of trial rafting runs ensued.

“It just never occurred to us that there may be rapids on the Ottawa but it’s got world-wide attention now,” Kowalski says. “There’s no place better for rafting and for kayaking. The Ottawa is prob- ably the best playboating river in the world.”

Thirty-three summers later the Ottawa River will be the stage for the world’s best freestyle paddlers. International athletes will be pulling off moves created on the Ottawa and paddling boats designed and tested on it.

Not bad for a river that wasn’t supposed have rapids.

UPPER JOHNSTON FALLS, BANFF ALBERTA

by Neil Etienne

From the moment a 19-year-old Tao Berman and crew began testing Upper Johnston Falls in Alberta’s Banff National Park more than seven years ago, it has been kayaking’s greatest focal point for the general public.

Before what would become a world-record event even happened, its appeal was obvious. More than 100 dumbstruck onlookers, some even wailing in fear, lined the park’s pathways and lookout spots just to catch a glimpse of what was going on. Almost instantly, video circulated worldwide in easy-to-digest, jaw-dropping simplicity.

On August 23, 1999 Tao Berman’s run of Johnston Falls broke the waterfall record for height at the time by about 20 feet but he also broke another barrier—whitewater kayaking became mainstream extreme.

“I didn’t realize just how much exposure that drop was going to get. With that one I wasn’t looking for exposure, just a 100-foot fall to run. People started to recognize me who had never paddled before. That’s when I noticed things were starting to get different.” Berman explains.

The plunge made headlines on NBC, Sports Illus- trated, Extra, and even Ripley’s Believe It Or Not. Since then, it has been a whirlwind of attention for Tao, and in turn, kayaking. NBC’s Jeep World of Adventure Sports approached him in 2004, asking what he was up to next. “Lacy Falls, British Columbia,” was Berman’s reply.

More rock quarry than waterfall, it is difficult to fathom the remote coastal stairway sluice of Lacy Falls as one of the more pivotal locations in recent whitewater history. But it too dropped extreme kayaking into a mainstream audience. This time with 20 different camera crews on hand, footage hit CNN, Fox News, the Discovery Channel, Real TV, the Outdoor Life Network and far, far beyond.

Careening down the slick, snaking conduit of inches-deep water, hitting more than 65 kilometres per hour, Berman’s 280-foot toboggan ride to the Pacific Ocean was so enthralling, terrifying and immediate, it was ex- actly what mass media and the TV viewing public con- sume and respect.

“Tao’s descent of Lacy Falls was watched by roughly a million viewers on NBC’s Jeep World of Adventure Sports in its premier airing,” explains the show’s Executive Di- rector Rufus Frost. “Not surprisingly, we were drawn to cover Tao and his attempt at this descent because it was a dramatic feat that would resonate with viewers who did not follow the sport of kayaking.”

This article first appeared in the Spring 2007 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2007 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions here.

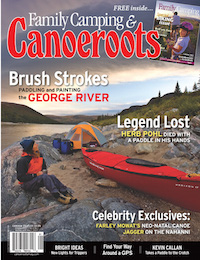

This article first appeared in the Spring 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2007 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions