On Vancouver Island’s West Coast, stories grow as fast and tall as the fat red cedars and amazon Douglas firs they’re told under. The characters grow larger than life and their feats beyond human. Take the tales of Cougar Annie, who is rumoured to have shot a cougar one-handed, dealt with more than one husband by force, withstood the shelling from a Japanese subma- rine and cultivated a garden of exotic plants amidst the wild coastal rainforest. Tall tales indeed, except these stories are true. Cougar Lady really did earn her name from her ability to dispatch meddling big cats and black bears and she made a life and a horticultural career for herself far from civilization in an environment where it rains almost every day from October until April.

So says Margaret Horsfield in her book Cougar Annie’s Garden. By the time I finished reading the introduction I was inspired to visit the storied garden and see for myself if the rumours were true that after years of neglect, Annie’s exotics were blooming once more.

So I planned a seven-day kayak trip. Beginning in Gold River, a remote West Coast logging town deep in Vancouver Island’s Nootka Sound, I would make my way to the exposed outer coast, paddle south around the noto- rious headland of Estevan Point to Hesquiat Harbour and visit the famed garden at Boat Basin. Then I would zigzag my way further south through the forested islands of Clayoquot Sound to the resort town of Tofino. On the way would be plenty of solitude to give me a taste of Cougar Annie’s life on the edge.

At the docks in Gold River, I loaded my gear aboard the Uchuck III, a former World War II minesweeper that now runs goods and people out to the coast’s remote lodges, homes and camps. With my kayak on board, the Uchuck motored west through the channels leading to Vancouver Island’s outer coast. The forested mountain- sides opened up to reveal snowcapped peaks behind them, fishermen fighting salmon and the odd curious

gaze of a sea lion or seal. Nearing the Pacific, the boat began to roll on a light swell. The Nootka Lighthouse appeared, marking the southern tip of Nootka Island and the entrance to the mouth of the sound. The Uchuck docked nearby at the historic coastal village of Friendly Cove. Today the settlement contains little more than a church, a graveyard, a single house, derelict foundations and a fallen totem pole. It is the landing site of Captain James Cook, the first European to set foot in B.C., and once an important summer residence for the local Mowachaht people. That was back when there were thousands of First Nations spread along the coast in pros- perous communities, and the way it was in 1915 when a woman named Ada Annie Rae-Arthur arrived on the coast with her husband Willie for a clean start and a new life.

The drug problems of today’s Vancouver were problems 90 years ago, and Willie was addicted to the city’s opium dens. The community of Boat Basin, a full day’s travel from Tofino, was remote enough to be free from temptation. Like few others, Annie stayed long enough to witness the decline of the Mowachaht. Until 1986, long after her neighbours had dwindled to none and she had gone blind, Annie stayed at her garden, not leaving for years at a time. She spent 70 years out here; I would spend seven days.

Icrossed the channel from Friendly Cove to the southern edge of Nootka Sound with the waves splashing at my side, glad to be alone on the ocean. I felt like a coastal explorer, with empty beaches, wave-washed cliffs, crashing surf and dense forest on one side, and open ocean, the odd sea otter, seals and sea birds on the other. I made camp at one of the many white sand beaches. Wolf, deer, and bear tracks dimpled the sand in lines that disap- peared into piles of bull kelp. I expected to see hand-sized cat-tracks too, here on Annie’s turf.

Cougar hunters were held in high regard amongst the pioneers of old, and Annie was the big-cat hunter’s queen. The animals were regular visitors to her garden, and she is reputed to have trapped and shot 70 to 80. Sometimes she would bait them with young goats; other times she would find them treed. She even shot them one-handed in the dark. When she heard the traps snap at night she would check them with a lamp in one hand and a gun in the other. Despite failing eyesight, she never missed a shot.

Annie’s cougar hunting was a profitable business— cougars earned bounties until the late ‘70s, plus there was always demand for hides. Annie was never one to miss a chance to make money—she also sold bulbs and plants from her garden and tended a store and post office. The exotic shrubs, bulbs, fruit trees and flowers Annie culti- vated were not adapted to this rainforest climate, yet her plants flourished and found buyers as far away as Manitoba.

The next stage of my journey took me around the headland of Estevan Point into the protected waters of Hesquiat Harbour and Boat Basin, Cougar Annie’s home. Estevan Point sticks out of Vancouver Island’s western profile like a pimple on a teenager’s face, bearing the brunt of every storm. It also bore the brunt of the only military attack on Canadian soil in recent history. One day during World War II, Annie spotted a submarine in Boat Basin. That night it opened fire on the Estevan Point Lighthouse. Shells were found all over the area for 30 years. Canadian military officials played down the attack, but everyone assumed it was a Japanese submarine.

Puzzling to many was, and is, why the Japanese would sail across the Pacific to attack a lighthouse in the middle of nowhere. Conspiracy theorists argued that it was actually an American submarine, that the States bombed their ally to keep Canada’s resolve firmly in the war.

Luckily I had calm conditions for paddling around this proboscis-shaped war zone into Hesquiat Harbour. Boat Basin lies at the harbour’s far end. I camped on a long, curving stretch of sand scooped out of the backside of Estevan Point, one hour’s paddle from the garden. I fell asleep that night trying to picture the garden and imagine what I would find the following day. I woke early with a nervous anticipation usually reserved for competitions and first dates. I packed, and tore up the four knots to Cougar Annie’s in record time.

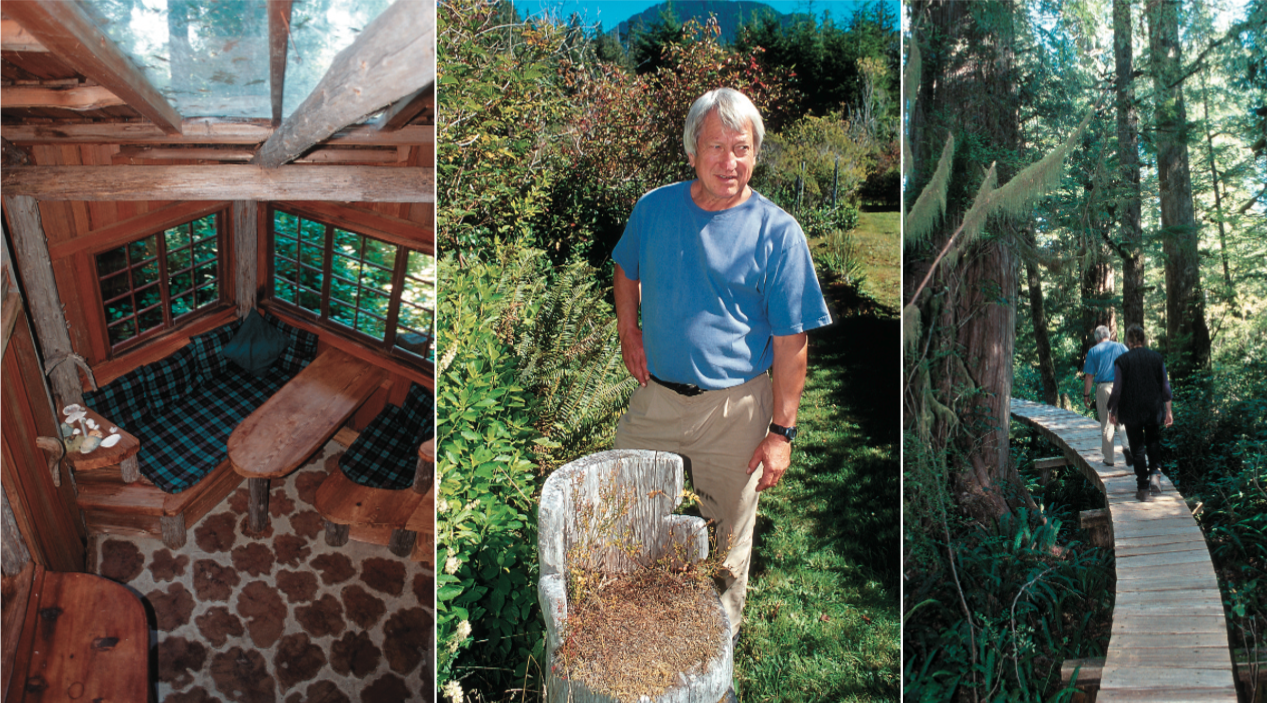

A new boardwalk leads from tidal water through a cedar swamp and up a short hill to the garden. Once only a rare few stopped here, but the garden is becoming famous. Float planes and sightseeing boats now drop in with tourists. But I was the only one around in the early morning hours this day.

I marvelled at the small room that was a post office and store. I walked down plant-lined boardwalks that beckoned me farther into the garden. I gazed in awe at the size of some of the old-growth beams and boards used for building. My eyes were distracted by the hundreds of exotic shrubs, trees and flowers blooming in pocket gardens. Wind whispered in the trees and bugs and birds hummed their tunes. And I was reminded of Annie’s reputation by the rusty traps hanging from trees.

One building, sinking into the ground, was obviously Annie’s home. I looked inside the one-room house. “Eleven kids,” I whispered. Over 70 years Annie raised 11 children and had four husbands come and go—either by death or desertion. After Willie died, Annie advertised for a husband alongside her nursery ads in two western- Canadian newspapers. George Campbell was one of those who replied and came to live at Boat Basin. Evidence suggests he beat Annie, and, not long after arriving, Campbell died suspiciously of a gunshot wound. Annie’s explanations varied between “it went off accidentally while he was cleaning it” to “it went off accidentally when he threatened to kill me.”

In Annie’s early days the area was busy with a thriving aboriginal, missionary and immigrant pioneer com- munity—enough to make a store and post office viable. Later on, Annie’s only customer was herself. Somehow she was impervious to the multiple forces that drew everyone else away. Today the only residents are a few Mowachaht at the remote reserve on Hesquiat Harbour’s northwest shore and Peter Buckland, who lives full-time at the garden.

Buckland was no stranger to life on the West Coast. He built a small prospector cabin close to Nootka Sound and spent his share of alone time there, whenever he could get away from his law profession in Vancouver. In Annie’s later years, he visited the garden to help out. He stayed for as long as he could spare before returning to his practice in the city.

In 1987, after Annie’s death, Buckland bought her homestead, moved in and began rescuing the garden from the encroaching forest. Partway through my visit I bumped into Buckland, a handsome grey-haired man of the woods. He was friendly and welcoming but not in a “tell all your friends to come here too” kind of way. He just seemed glad to have someone to chat with for a few minutes while pointing out the sights with his work- worn hands. I complimented him on the state of the gar- den, the flowers blooming, the orderly paths and under- control shrubs and trees.

“I practice what I call chainsaw gardening,” he said. Using a chainsaw, axe and machete as gardening tools, he has been reclaiming the former garden. Under the salmonberry and salal, he found the garden struggling to survive. He discovered the fruit trees still bore fruit and most of the shrubs, perennials and other flowers still bloomed despite the heavy cloak of the intruding forest. After 15 years of hard work he still turns up forgotten sections of garden and the plants hidden in them.

Buckland has built himself an incredible abode from the surrounding forest and he plans on being here for many years to come. He has built new cabins, constructed two kilometres of boardwalk and opened the garden to the public. He recently turned the garden over to the not-for-profit Boat Basin Society to ensure its preservation. For the cost of a $50 Society membership, anyone can come to the garden, wander through the oasis protected by towering stands of fir and cedar, and contemplate the tenacity of two modern-day pioneers.

What Cougar Annie and Peter Buckland had done inspired me. I had commitments back home and packed up to head for Tofino, but I was already working out a plan to come back and carve a living for myself out of the coastal rainforest. I paddled south and pulled up on a pocket beach for the last night of my trip, eyeing the forest for a spot to build a cabin and set up a garden as I unrolled my sleeping bag on the sand.

Sleep came easily but during the night I woke to the breaking-twig sounds of an animal hunting in the dark. I stayed awake nervously waiting for a cougar to pounce and shred the few layers of nylon that encased its next meal. A quote from Horsfield came to mind: “When you shoot a cougar, sight fast and aim for its chest. That way you’ll hit the giant cat’s heart,” Annie advised a newspaper reporter in 1957.

I didn’t have a gun but I did have a knife. In a sleep-deprived lunacy, I grabbed my headlamp and the knife, took a deep breath, and turned to face the cougar. Two red eyes flashed in the bush, then turned and ran. With a sharp dose of reality my fears dissolved, but so did my dreams of a life in the bush. Like many before me I realized that it takes a rare type of person to make it out here. I woke the next morning and, like the mouse that had disturbed my slumber, high-tailed it home.

When he’s not exploring the mountains and shores of Vancouver Island, Ryan Stuart lives, writes and enjoys human company in Courtenay, B.C.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2003 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2003 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2003 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2003 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This two-part article was first published in the Early Summer 2003 and Summer 2003 issues of Rapid Magazine. It was republished in part in the Spring 2008 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This two-part article was first published in the Early Summer 2003 and Summer 2003 issues of Rapid Magazine. It was republished in part in the Spring 2008 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2003 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Summer 2003 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions