Dagger GT / GTX Specs

Length: 7 ft 10 in / 8 ft 2 in

Width: 24 in / 25.5 in

Volume: 67 gal / 76 gal

Weight: 38 lbs / 40 lbs

Cockpit: 34 in x19 in / 34 in x 19 in

Paddler Weight: 90-180 lbs / 140-230 lbs

Standard Features: Precision seat, thigh braces and Clutch Outfitting System

MSRP: $1,495.00

dagger.com

With all the hype freestyle paddling has received it is easy to forget that a vast majority of paddlers prefer running rivers.

For park and play paddlers the concept of river running consists of limping down the river, helplessly floating past the hero ferries of yesterday in boats designed to maximize their freestyle potential.

Yes, it’s true some playboats are decent enough river runners and they’ve helped push the envelope of what is acceptable but they lack the exhilarating all-river performance of longer traditional boats. Without any more editorial tangents let me introduce the new Dagger GT.

Dagger Kayak’s goal was not to create a playboat that could river run nor to design a river runner that could play…but to create a boat that was equally balanced at both. Partially as a replacement of the popular Redline series and partially as an evolution of the more playful Outlaw/Showdown series, the new GT and GTX were borne of a desire to fill a niche that was left empty. Dagger wanted a boat that is equally at home running harder rivers and playing by today’s new school standards.

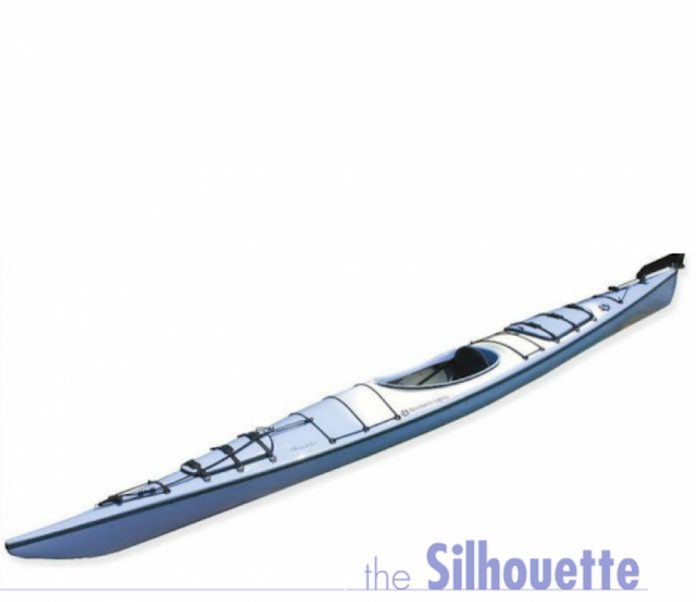

An 8-foot kayak by Dagger Kayak’s for river running and surfing

Coming in at just under 8 feet in length, Dagger Kayak’s GT splits the difference between traditional river runners and park and play boats. If you’re the type of person who likes a sweeping oversimplification of design we’d say the GT series is an old school RPM combined with a new school ID.

Like the Dagger ID, the GT and GTX are relatively narrow and have a very slight curvature across the planing surface combined with raised edges. The design theory is that you can more easily tilt from edge to edge than you can with a wider, completely flat hulled boat. Rather than going with the more traditional river running continuous rocker, Dagger shortened the planing surface putting a hard rocker break just ahead and behind the paddler.

Mark Lyle of the Dagger design team explains: “We went through five prototypes before we had what we wanted. There is a lot of trial and error involved in boat design, more than some people might realize. It was important for the boat to feel loose on a wave but we noticed that a longer planing surface made a lot of other moves harder. As soon as we shortened the planing surface we could boof and pivot better and the boat responded better to paddler input.”

The GT’s kayak outfitting accessories

Dagger’s new Clutch Outfitting isn’t industry leading but it contains all the essentials a paddler requires to be safe and comfortable. The kit has a certain sense of familiarity to it that leaves paddlers with a feeling of self-empowerment instead of shyly asking the store staff what the new auto-ratcheting, micro-adjustable, heat-moldable, thermo-resin doodad does to ensure they can get out safely.

The peel and stick hip pads and assorted foam shims are all pretty self-explanatory and likely revolutionary compared to the typical river runner’s blue foam and duct tape jobs—brutal. The fully adjustable thigh braces are a pretty slick system with no exposed bolts and the seat and Bomber Gear backband are fully adjustable. Throwing in a compact screwdriver and a little wrench would be a nice touch.

Dagger Kayaks’ GT adjustable sit-in kayak seats

Short people win once again; they can move the adjustable bulkhead wherever they want. The seat is adjustable from front to back but should be set for boat performance not fit (more on that later). With the seat in a centered or forward position the narrow bow results in a pretty snug fit for tall or large footed paddlers.

Dagger Kayak’s GT is a boat you are likely to spend hours in and not likely to flatwater cartwheel so taller paddlers of any weight might need to try the GTX to be comfortable. Tip: removing the foam from the plastic bulkhead buys you almost another inch. Coming back to the GT after paddling boats like the G-Force we realized foot and leg comfort is more a factor of width than length. Despite the added length of the GT, the narrow bow made for a limited foot room.

A balanced whitewater kayak that promotes confidence

The first thing we noticed is that you need to get the GT trimmed properly—balanced from front to back or even slightly bow heavy. The short planing surface and hard rocker break just behind the seat allows you to, on command, roll back onto your stern raising the bow for boofing and crossing larger eddy lines.

If you’re not trimmed properly the boat is slower, you will fall off otherwise nice surf waves and you tend to wheelie or plane across currents instead of carving through them. Forget about working to keep the bow up, it doesn’t dive or pearl like the Redline.

Having a similar hull to the ID, the GT is an extremely user-friendly boat. With its raised edges and lots of flare, we were crossing eddy lines with hardly any tilt and the twitchy stern of the Redline is gone. The secondary and final stability promotes confidence. Paddlers accustomed to edgier boats found it a soft carver, those used to mushy modern playboats loved it.

Either way, both agreed the GT provides the experienced paddler the comfort zone needed for harder river runs while beginners and intermediates benefit from having a boat for which they don’t need to remember all the rules. One tester summed it up best, “I haven’t felt so at home in a boat since my RPM.” Why is the RPM one of the best selling boats? Because people are able to paddle it.

A user-friendly 8-foot kayak with lots of rocker

Eight feet and lots of rocker might be the perfect combo for blending flat, green all-day front surfs and respectable spinning. For a little perspective, the GT is only an inch longer than Wave Sport’s XXX. Get in a munchy side surf and you realize the GT is a longer, larger volume boat, and it’s not as easy as we remember to blast our way out. Which is okay, most likely GT owners aren’t really into big munchy holes anyway.

River runners aren’t hanging onto their five-year-old boats because they are cheap, there just isn’t a huge selection of new boats satisfying their needs. The evolution of rodeo boats has shown us that you don’t need ten feet of plastic to get down a river, but the hottest freestylers are now too specialized to be passed down and resold as all-river boats.

By combining the slippery feeling of their freestyle planing hulls with the user-friendliness of older, popular designs like the Redline and RPM, Dagger has the makings of another winner in their line-up. For 2003 Dagger will round out the GT series with a smaller version making the GT family a good choice for free-boaters, schools, clubs, new boaters and anyone else looking to catch an eddy. For more top picks and expert reviews, check out Paddling Magazine’s guide to the best whitewater kayaks here.

For the love of surf and the love of river running, Dagger Kayak’s GT is your perfect balance. Feature Photo: Rapid Staff

This article first appeared in the Fall 2002 issue of Adventure Kayak magazine. For more boat reviews, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2002 issue of Adventure Kayak magazine. For more boat reviews, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2002 issue of Adventure Kayak magazine. For more boat reviews, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Fall 2002 issue of Adventure Kayak magazine. For more boat reviews, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Summer 2002 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Summer 2002 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions