Last November, Dane Jackson won the Green River Narrows Race with a new course record of four minutes and four seconds. Dane is 5’7” wearing river shoes, with an arm span roughly one inch wider than his height, and weighs about 154 pounds. The 11-time women’s champion, Adriene Levknecht, is 5’2”, also has a wingspan around one inch wider than her height and weighs 130 pounds.

No matter the sport, spectator conversation inevitably drifts toward sizing up the players. In a boxing contest, it might be whether the challenger can slip inside the reach of the reigning champ. In a basketball game, it might be the height and reach of two opposing centers. Every sport has its element of advantage based on physical build of the players.

Can height, weight, arm span or some other attribute provide an edge when it comes to racing a plastic kayak through class V whitewater? Is there an archetype for an extreme whitewater racer?

Mainstream sports have studied this extensively. While body shape is, of course, not the defining factor in athleticism, researchers know elite swimmers are typically tall with long arms and big feet to move more water. The fastest marathon runners usually have light frames to go the distance. Similarly, Kentucky Derby jockeys are small in stature, while Olympic weightlifters tend to have relatively short arms and legs, which makes their bodies more effective levers.

Not surprisingly, there hasn’t been much research associated with the ideal physique for pounding Red Bull and careening down mountainside torrents as fast as lactic tolerance allows. But we can look to a similar paddling discipline for guidance—the Olympic slalom course.

The build of a slalom paddler

“Is there a suitable body profile for whitewater slalom specialization?” asks Jan Busta, a researcher of sports at Charles University in the Czech Republic. “Yes. Elite male canoe slalom paddlers and kayak paddlers have an average body weight of 165 pounds and height of 5’11”. We can characterize their somatotype as ectomorph-mesomorph.”

Busta published a research study in a 2018 edition of the Journal of Outdoor Activities titled, “Anthropometric, physiological and performance profiles of elite and sub-elite canoe slalom athletes.” He is a canoe slalom paddler himself and coach for the decorated Czech national team. He conducted the study using top male canoeists in the Czech Republic by taking a variety of body measurements and performing a battery of strength and fitness tests. The scientific phrase he refers to as somatotype means body shape. Ectomorph-mesomorph translates to lean and muscular.

The 10 finalists of the men’s kayak at the 2016 Olympics had an average height of 5’11” and a weight of 163 pounds, so Busta’s numbers are pretty spot on.

The build of an extreme whitewater racer

To gather some data specific to extreme racers, photographer Regina Nicolardi and I showed up at the take-out of the Green River Narrows to survey competitors before the 2019 Green Race in November.

Our survey included 28 racers across each class and included six of the top 10 overall finishers. We used a tape measure and a bathroom scale to measure height, arm span and weight. Paddlers wore their shoes and drysuits while the rain fell heavily in a typical autumn scene for the southeastern United States. Without a doubt, there is some margin for error in our work. But we hoped we might find at least a few figures that stood out.

Our findings: The mean height of a surveyed competitor regardless of boat class or gender was 5’9”, weight 172 pounds, arm span 71 inches. Those numbers changed some when we dialed it down to the six top 10 finishers: 5’11” and 172 pounds, with an arm span of 73 inches.

Busta’s paper also shows the average arm span is greater than height, but he doesn’t believe this is an advantage in a sport with such deft maneuvering as slalom, as it requires more energy to get the boat back to speed. Extreme races require maneuvering, but also provide longer periods of sustained downstream momentum.

What about weight? Is there a divergence between slalom and sprinting downstream in a plastic kayak?

“Slalom boats are quite small. To be heavy in a slalom boat has negative hydrodynamic consequences. There is bigger resistance of the boat in the water,” says Busta. “Extreme kayaks have a bigger load capacity, which means paddlers could be heavier, around 187 pounds, but they must still have the perfect relation between power and body weight.”

Different bodies in similar boats

Our bodies are not a lone operator in this sport. They fit within a watercraft, and our assets play a role in how the craft interacts with the river. Part of the draw to observing the Green Race to study these elite athletes is how the race hinges on the use of long boat design. The options are essentially limited to one model per manufacturer. No matter your size, you are racing in a similar boat on the same course as someone who may be of drastically different measurements. Are differences such as weight enough to play a role in the hydrodynamic interaction of our boats in the river?

As a four-time world freestyle champion and the former president of Jackson Kayak, Eric Jackson says he doesn’t believe there is one type of physique with an advantage in extreme racing. He claims long kayaks are designed to ergonomically fit a range of paddlers, from 120 to 240 pounds and heights from 5’2” to 6’3”.

“These boats tend to be a standard weight, so the lighter you are, the more mass you have to accelerate and control for your weight,” he adds, which would put lighter, shorter paddlers at a disadvantage.

Putting this theory to practice, perennial Green Race women’s champion, Adriene Levknecht, is well below the mean measurements of the top 10 finishers. She is accelerating a boat of equal mass to that of fellow Dagger paddlers such as Brad McMillan, who is 196 pounds and 6’1”, who finished ninth. Levknecht was 10 seconds slower, in 16th place. Both paddled the Dagger Vanguard, accelerating the same mass down Go Left, Gorilla and Rapid Transit.

Levknecht is well below the mean, McMillan is substantially above. Dane Jackson, a three-time Green Race winner himself, is shorter and lighter than the mean as well. So, is there scientifically a physical trait providing an advantage in racing class V whitewater?

With such a small pool of elite whitewater athletes to sample from, further analysis is required. In the meantime, the skills and willingness to descend a class V rapid may have to be edge enough.

Joe Potoczak is a freelance writer based in eastern Pennsylvania. His work has appeared in Canoe & Kayak, Blue Ridge Outdoors and Outside.

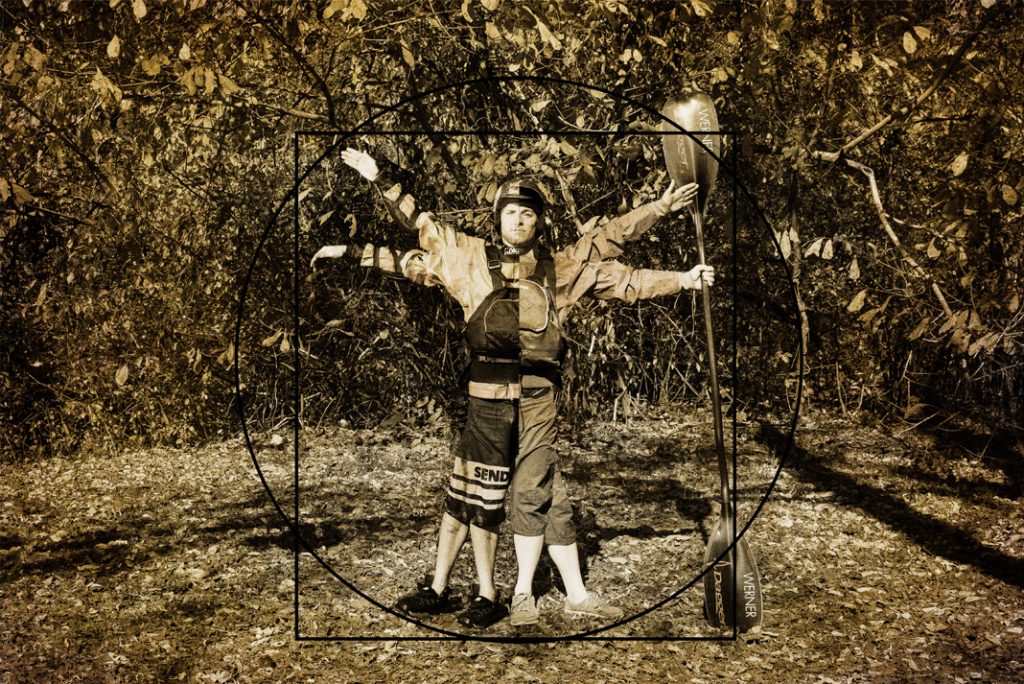

Like the Vitruvian Man but with more smelly neoprene. | Photo: Regina Nicolardi