At 13 years old, Sage Donnelly of Carson City, Nevada, already has more than a decade of whitewater experience. She’s beating adult women in freestyle, C1 and K1 slalom. Off the competition circuit, she runs waterfalls and class V rivers.

You wouldn’t have seen a phemon this young 10 years ago, before Jackson Kayak introduced the Fun series of whitewater kayaks for kids under nine and as small as 30 pounds. Or before youngsters like EJ’s daughter Emily and son Dane, who ran his first class IV at age four, entered the spotlight to inspire kids and parents alike.

Since the Fun came out in 2005, designer Eric “EJ” Jackson says the average age of entry into whitewater kayaking has been cut in half, to around age eight. Youth participation statistics from the Outdoor Industry Association report that the number of whitewater kayakers aged six to 17 has more than doubled in the last five years. The number of youth participating in rec and touring is also up, though not as dramatically.

It’s the recent bounty of kid-friendly boats that has allowed paddling schools and local clubs to structure their programs for ever-younger participants and, in some lucky towns, make kayaking just another option, like little league or minor hockey. It’s a scene you wouldn’t have come across a few years ago, confirms Jackson Kayak’s marketing director James McBeath. “It used to be the age-old excuse that, ‘I gave up kayaking because I had kids.’ Now, with smaller boats, you can really bring them with you,” he says.

NEW PRIORITIES

Thanks in part to an aging Boomer population, kids have become a priority across the whole outdoor industry. Companies are heeding the warning of Richard Louv, whose 2005 book Last Child in the Woods coined the term Nature Deficit Disorder, and fighting for their future pay checks in the age of iPhone.

Confluence Watersports, the parent company of Dagger and WaveSport, is now at the forefront of the industry’s youth drive, recognizing that today’s boomer-driven boat sales won’t last. At the 2013 Outdoor Retailer Summer Market, getting a new generation outside was identified as the most pressing issue facing the industry today. Confluence was also a platinum sponsor of the Outsider’s Ball, a fundraiser for youth outdoor programs. It’s no surprise that 2014 features an explosion of kids-specific equipment across the paddlesports market, including all manners of kayaks, paddleboards and accessories.

Companies are tackling the kids’ market in a couple of ways, says Mark Kelly, paddlesports buyer for outdoor retailer MEC.

SWALLOWING MARGINS

For one, many are swallowing their profit to offer premium kids products. High-end kids equipment includes the nine-foot NRS Jester paddleboard, the composite Raven touring kayak by Current Designs and Nova Craft’s 29-pound Teddy, a 12-foot tandem canoe for kids. Competing in the whitewater market, Pyranha makes the TG Lite and the Rebel, which fits paddlers 25 pounds and up. WaveSport, Dagger and others offer kayaks for those 60 pounds and up. All these products serve the small market of enthusiast parents, who’ll pay to outfit future champions with bantam versions of their own equipment, or institutions, including schools and clubs.

At the same time, technology trickle-down is enabling decent kids’ products to be offered at a lower price point.

“Companies are identifying kids as a robust market but most parents aren’t interested in higher-quality, higher-priced products that their kids are just going to grow out of, so the market has reacted,” says Kelly. One of MEC’s hottest sellers this year is a barebones kids’ sit-on-top that sells for $100. A small step up are true rec touring kayaks in the $300 range, like the Old Town Heron Jr., the Perception Prodigy XS or the Jackson Mini Tripper. The Vibe 80 by Pelican has filled the same niche (affordable, lightweight and indestructible) in paddleboarding.

Jackson Kayak’s success notwithstanding, bringing kids designs to fruition isn’t seen as a moneymaker, according to Confluence sales rep Paul Brittain. It’s about playing the long game. “We’ve made a commitment that, short of losing money, kids’ boating stays a priority. It’s the right thing to do. This is our future, we should invest in it.”

Manufacturers are betting their investment will pay off down the road. With kids-friendly boats now in every discipline, each type of paddling may soon have its Sage Donnelly.

Tim Shuff is a former editor and regular contributor to Adventure Kayak magazine.

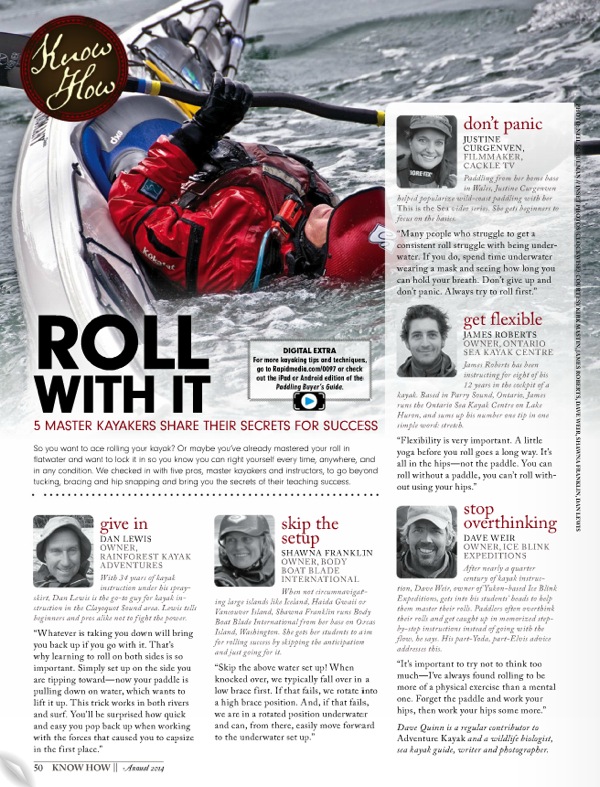

This article originally appeared in the 2014 Paddling Buyer’s Guide. Download our free iPad/iPhone/iPod Touch App or Android App or read it on your desktop here.

This article was first published in the Early Summer 2013 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.

This article was first published in the Early Summer 2013 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.

This article was first published in the Early Summer 2010 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article was first published in the Early Summer 2010 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.