Ready to tack?” came the call from the helm. “Ready, ready, ready,” yelled out the others on the sailboat. “Ready,” I muttered, reaching for the jib sheet that was tangled around my foot and realizing that I was anything but ready. I quickly untangled it, released one jib sheet, took up the other and crossed over the centerboard, slamming my shin painfully into its casing.

Pulling the slack out of the jib sheet, I became aware that it was hung up on something (likely some part of me). It was much longer than I remembered it being, but I was finally able to tighten it up and cleat it. For the first time in a while, I was a student, and an awkward one at that.

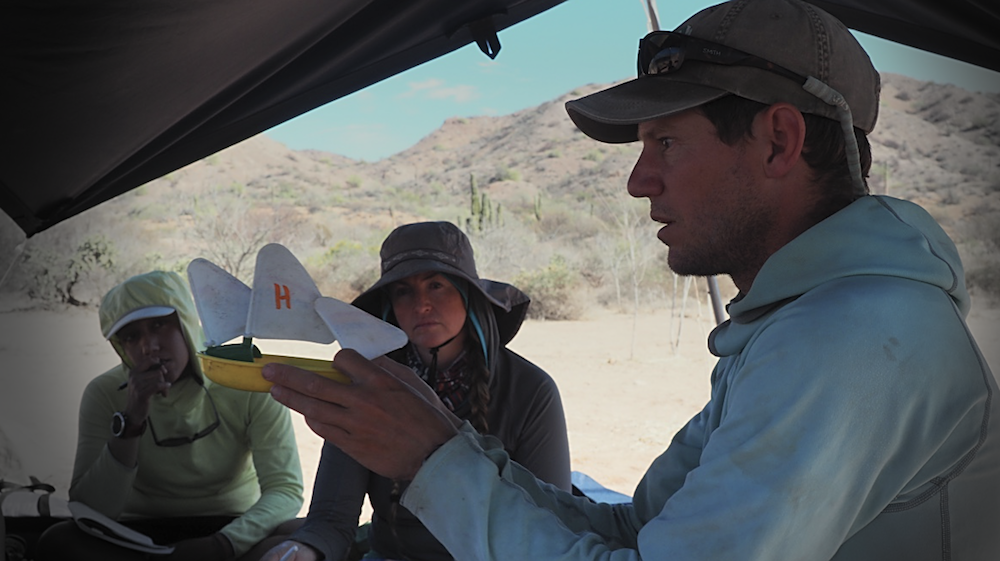

I was in Baja, and over the next 25 days I’d be learning to sail on a National Outdoor Leadership School Sailing Seminar and Clinic, a course specifically designed for current NOLS instructors who are certified in another discipline. As a sea kayak instructor, sailing seemed an obvious transition, as I assumed many skills would transfer nicely: seapersonship, navigation, wind, and tides and current, just to name a few. While it’s true these are indeed useful skills to possess when learning to sail, I quickly realized that the sailing-specific technical skills I didn’t have far outnumbered the skills that I already had.

I was an absolute beginner.

I found this quite humbling and reflected on how my students likely have similar feelings of awkwardness.

Throughout the course we worked on technical skills and rotated through the roles; controlling the jib and main sheets (sheets are, simply put, ropes attached to sails, and the jib and main are types of sails) and steering at the helm. We learned how to travel from a shallow-water anchor to a deep-water anchor and how to set up the sailboat for sailing. We also learned how to recover after a capsize and how to land in surf (both of which are a blast).

Every night I’d curl up in my sleeping bag under the stars and think of all of the things that I’d learned. Questions would come to me, and I’d make a mental note to remember to ask them in the morning or to look them up in one of the reading resources that we had with us. Usually though, my brain was so full that these thoughts would dissipate overnight.

It’s very easy to forget what it’s like to be a student, and putting myself in this role pushed me to experience the frustrations, trials, successes and emotions that go along with the learning process. I find this important because it allows me to empathize with my students, and empathy, paired with a fine-tuned class, creates the best learning environment possible.

The final day on the water we had calm seas and a slight breeze. At one point we jumped out of the sailboat for a swim. Later in the day a Dorado (mahi mahi) leapt out of the water, seemingly mocking our extended handlines. The day on the water had been carefree and beautiful, and the things that we had learned over the past 25 days were settling in to a point in both our brains and our bodies where we didn’t have to try quite so hard. My bruises had faded to yellow, and I felt a soothing connection to the boat, its parts and the way that it gently rocked on the water. I had moved through the learning progression, and I smiled to myself as I realized that I was now (almost) “ready to tack.”

Main image: Courtesy Meg Lavery