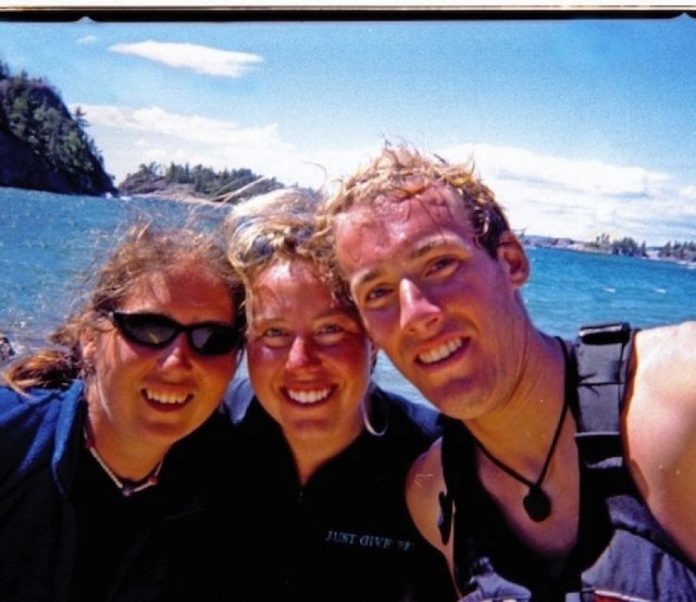

The fleeting moment in time captured in the above photo—like every moment in our lives, and every photograph—is unique and unrepeatable. For me, that’s the magic of photography.

In the popular doctrine of photography, this is not a great shot. A professional eye would notice the crooked horizon, over-exposed sky and not-quite-sharp focus. A better composed portrait would not be—or at least not reveal that it was—shot at arm’s length by the subject. Nor would it be shot with a disposable camera purchased pre-loaded with Kodak Max 400 at Wal-Mart.

Professional photography instructor and frequent contributor Neil Schulman notes that in a strong image, the photographer “creates tension and anticipation through composition,” urging the viewer to imagine what happens next. This image contains no such tension, the faces seem relaxed, the anticipation passed. But that is precisely why I like it.

The disheveled hair, tanned faces and satis- fied smiles hint at an exciting story—the subtle “Just give ‘er” stitched into the polypro suggests that it might even be an epic story…

Conor called the Rock to Rock a “rite of passage”—a balls-to-the-wall straight shot down 80 kilometers of Lake Superior coast from Michipicoten Bay’s Rock Island to Sinclair Cove’s Agawa Rock. We slipped our kayaks into the river and drifted out onto the lake at 2:30 a.m. under a moonless sky. As dawn broke somewhere off Grindstone Point, a thick fogbank closed in around us and we placed all of our faith in the magnetically charged needle on Conor’s bow. Another hour of paddling and the fog lifted, the wind came howling out of the north and the lake blew itself into a seething frenzy.

Conor sailed down the wave faces, hooting with delight. The 22-foot tandem that I sterned was less nimble—it wallowed in the troughs like a wounded water buffalo, burying

Kim to her armpits while I perched high and dry on the following wave crest. Conor and the distant shore alternately appeared and vanished behind the lumpy wave tops.

As we neared the soaring rose granite and ancient pictographs of Agawa Rock, the lake seemed to tear at our victory with the combined power of its many manitous. Fuelled by Twizzlers, Mars bars, vitamin I and a fierce desire to stay upright (Kim and I had yet to master the tandem roll), we battled with sets reaching 10 feet high. I’m sure my hapless bow partner wasn’t exactly filled with confidence by my invocation, repeated loudly as each wave descend- ed over us,“holy shit, holyshit, HOLYSHIT!”

We reheated wind-chilled limbs on the sun-warmed, black basalt “survival rocks” in Sinclair Cove before huddling for this self-portrait. When I look at it now, I see all the excitement, euphoria and exhaustion of our 13-hour accomplishment.

It’s said a photograph is worth a thousand words. If this is true—and, at the risk of making my job obsolete, I believe it can be (after all, I’ve just written 500 about this one)—than a photo annual, while light on text, is immeasurably rich in stories.

Senior editor Virginia Marshall has since upgraded her camera kit, but she still loves the written word.

This article was first published in the Summer/Fall 2012 issue of Rapid Magazine and was republished in the 2023 Paddling Buyer’s Guide.

This article was first published in the Summer/Fall 2012 issue of Rapid Magazine and was republished in the 2023 Paddling Buyer’s Guide.

This article first appeared in the Summer/Fall 2012 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Summer/Fall 2012 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions