This canoe routes destination article originally appeared in Canoeroots and Family Camping magazine.

The fur trade lasted three centuries, opening up North America. The couriers-du-bois voyageurs and Natives who traveled these waterways shaped modern transportation corridors, settlements and cultures. Retrace their paddle strokes along trade routes that once connected Montreal to Oregon and Hudson Bay to the Gulf of Mexico.

Lake Champlain

NEW YORK, QUEBEC AND VERMONT

Samuel de Champlain discovered this lake in the early 1600s after establishing New France. With the Richelieu River to the north and Hudson River to the south, it was part of a fur trade thoroughfare connecting the St. Lawrence to New York. The waterway was also a pivotal battleground during the War of 1812. Sandwiched between the Adirondacks and the Green Mountains, enjoy paddling Lake Champlain’s 80 scenic miles from end-to-end over seven days. The Lake Champlain Paddlers’ Trail consists of more than 600 campsites and 39 access points, providing endless route possibilities. www.lakechamplaincommittee.org

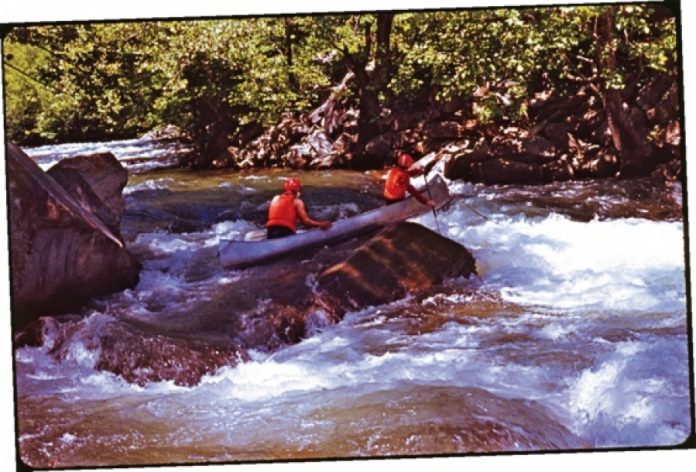

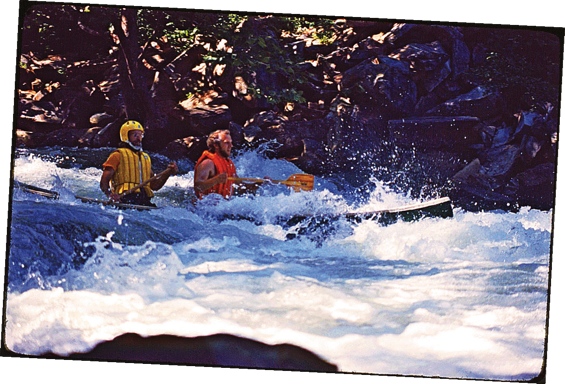

French River

ONTARIO

Ojibwa Indians named the iconic French River in the 1600s because it brought ex-plorers like Etienne Brulé. Traders would soon follow, transporting furs from western Canada through this corridor that links Montreal to the Great Lakes by way of the Ottawa and Mattawa rivers. Now a Canadian Heritage River, the French offers canoeists 70 miles of paddling through Canadian Shield and provincial parkland. Choose to navigate the abundant family-friendly whitewater or experience portages that have remained unchanged for over 300 years. www.ontarioparks.com

Des Plaines River

ILLINOIS

In 1670, French explorer René-Robert de La Salle set out on an expedition to secure an inland trade route connecting Montreal and New Orleans. The Des Plaines

River provided traders passage between Lake Michigan and the Mississippi. It runs 95 miles south through Illinois and offers paddling among some of the rarest remaining natural prairie. Forest and nature preserves line its banks—habitat for cormorants, egrets, herons and small mammals. Isle la Cache in Romeoville is home to a fur trade interpretive center and has one of nine canoe-only access points along the river.

York Factory Express

MANITOBA

York Factory served as the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Northern Department headquarters on Hudson Bay and operated as a trading post for over 270 years. It was the easternmost point of the York Factory Express, a trade route that connected the Oregon coast with Hudson Bay. The final leg of this traditional artery carried voyageurs from the Norway House outpost at the northern reaches of Lake Winnipeg to York Factory. This remote whitewater canoe route takes paddlers on a three-week, 375-mile trip past abandoned train lines and fur trade posts, old gravesites, pictographs and forgotten settlements. www.paddle.mb.ca

Columbia River

OREGON AND WASHINGTON

At the other end of the York Factory Express is the Columbia River. In 1807, fur trader, surveyor and mapmaker, David Thompson set out from the river’s source deep in the Canadian Rockies at Rocky Mountain House to explore the Columbia’s path to the Pacific. Meanwhile, American Fur Company owner, John Astor, established a fur trading post at modern day Astoria, Oregon, where the river meets the ocean. Retrace some of Thompson’s journey on The Lower Columbia River Water Trail—a 146-mile route from the Bonneville Dam past volcanic cliffs, wildlife refuges, museums, memorials and lighthouses to the Pacific Ocean at Astoria. www.columbiawatertrail.org

This article originally appeared in Canoeroots & Family Camping, Fall 2012. Download our freeiPad/iPhone/iPod Touch App or Android App or read it here.