When my eldest son Jason was 16, we planned a father–son kayaking trip from Flowerpot Island near Tobermory, Ontario, all the way home to Windsor. The first leg of this journey would take us down the east side of Lake Huron’s Bruce Peninsula to the town of Wiarton.

At daybreak on the first day the air was warm, hazy and heavy. Normally I would have checked the weather on my VHF, but I had made a foolish agreement with my son—no electronic distractions, no Walkman, no video games—so I did not bring the VHF radio either. It was a mistake I would never make again.

A mile offshore, the water was waxy smooth but there was a roll to it. To the northwest, there was a dark blue, steel- grey line in the sky.

A half-hour later came a noise like the drone of hundreds of motors behind us. Something big was moving in. Things darkened so fast, only minutes before the sky had been clear. The air began to swirl. Flowerpot Island, now miles behind us, vanished from left to right behind sheets of rain. We could now see the leading force of the wind front on the surface of the bay. There was no thunder, no lightning, just the deafening roar of rain racing full throttle over the emptiness toward us.

I knew it would reach us before we reached the mainland, still about 20 minutes away.

“THE SKY DID STRANGE AND AWESOME THINGS”

Things in the next moments happened very, very fast. The sky did strange and awesome things. The air temperature plummeted to that of a blustery November day. Boiling clouds of purple and green rolled towards the surface and us with the action of an exploding fireball.

I fixed my eyes on my son and—wham!— at that split second, it hit! This force of air was so violent that it blew me over. I struggled to brace and roll up into the maelstrom.

The low, green sky said “take shelter” to anyone from the Midwest. We knew this, yet there was no chance of shelter. Ex- panding contorted clouds, looking as they would burst, only acted as a harbinger of worse yet to come. The sheets of rain found us and giant drops stung as they hit, then hailstones added blows to the head.

Again I swung my gaze toward Jason. One cloud beyond him caught my attention. An ominous spin had begun and soon a funnel hung. The father instinct kicked in and I sprinted toward my son. I yelled to him to raft up but he could not hear.

The funnel, for some reason, held at a distance above the water. Below it, spray began to blast up from the seas as if some giant, invisible food processor had touched the surface. Blasts of spray began to rise and spin. Then, for a short moment, it all seemed to stop until—“whoosh”—the spinning spray jumped up and joined the cloud. Georgian Bay was being sucked up into the sky. The birth of a waterspout, right before our eyes!

I could not reach Jason in time.

When the waterspout came it was as if we were standing far too near railroad tracks as a speeding locomotive passed. Ears hurt. It was hard to breathe. Kayaks felt the pull toward it as metal to a magnet.

It missed.

We had survived.

Jason had held firm and strong. I was so proud of him.

Our ordeal was not over yet. The seas had become too large to land. We decided to paddle on to Lion’s Head Harbour, over 50 miles from Flowerpot Island. After nine and a half hours of paddling we entered the harbour just after dark and found a motel.

The next morning, I ventured outside to survey our chances of paddling. It was dreary and miserable. Some fishing tugs had pulled into the harbour during the night. The boys on the first tug welcomed me aboard and filled me in on a very bleak extended weath- er forecast: gale- and storm-force winds, rain and high waves for the next five days.

I called my wife: “Ingrid, can you get out the map of Ontario? See the village of Lions Head? Come and get us, love.”

Steve Lutsch has been an avid kayaker since the 1970s. He lives in Windsor, Ont. Jason went on to buy a fleet of kayaks. He likes rough water, but never wants to paddle 50 miles in one day again.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2008 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2008 issue of Rapid Magazine.

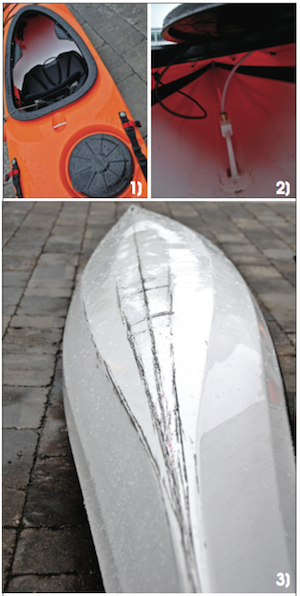

1) Features galore

1) Features galore

This article first appeared in the Summer 2008 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Summer 2008 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions