When I first saw a Greenland paddle I thought that such a tiny stick would only stir bubbles in the water. Then in 1999 during the St. Lawrence crossing race, I hosted the famous Greenland paddler Maligiaq Padilla in Quebec. This talented young man introduced me to the wonders of this traditional paddling tool.

The Greenland paddle is handled by the tip while keeping the other hand in the centre, forming an elongated lever. Although I still prefer to use a wide, European-style carbon paddle, this leverage effect instantly made a lot of sense as a way to gain efficiency. I started to practice moving my hands along the shaft of my conventional paddle until it became a reflex.

I can now rely on a good extended grip and take advantage of the simple physics of a lever while sweeping to turn my kayak in strong wind.

On one long crossing I used an extended paddle grip for a couple of hours to beat a strong side wind. The same technique can be used to stay on course if a skeg or rudder fails.

I also use an extended paddle when surfing to get a stronger rudder. Sometimes I apply an extended sculling brace to get foolproof support in choppy water. And if my roll fails twice, my next move is to apply an extended paddle roll, also known as a Pawlata roll. You can apply the same techniques to a crank shaft paddle with a bit of adaptation and extra practice.

MIX DIFFERENT METHODS TO DEVELOP COORDINATION

To begin, just practise moving your hands on the paddle shaft. There are several ways to do this. The slipping method is one option. First slip one of your hands to the paddle neck (where the shaft meets blade), keeping the other one near the centre. Another method is to relax your grip on one hand and push or pull the shaft from one side to the other. At the beginning, you will have to experiment with how much to relax and tighten your grip to control or release the shaft.

The gripping method works too: move one hand at a time from one position on the shaft to another by opening your hands completely. This method lets you move a hand out to the blade tip for even more leverage. The disadvantage is that when you release the grip on the shaft, you open the door to a fumble.

Using any combination of these methods, try moving your hands slowly at first along the shaft to develop coordination and proprioceptive acuity. Then practise sliding them quickly to any position.

To develop a kinaesthetic awareness of the blade on the water, scull the power face of the blade back and forth over the surface without looking at the paddle. If the blade sinks, ad- just the angle right away so you have a slight lifting angle.

Now test your reflexes by bracing with an extended paddle grip on one side 10 times, then on the other side. Then try alternating braces on one side and then the other. Try to do a low brace one side and a high brace the other, increasing the speed. Then try it blindfolded. Intuitively knowing how your blades are oriented at all times is crucial in rough water.

Once you have mastered this, you can truly “extend” your paddling horizons by using your paddle as a lever in any situation.

SAFETY TIPS

- Increase your reach gradually. Don’t exceed the leverage your body or paddle can handle (I have broken a couple of shafts trying this).

- Protect your body by always keeping your shoulders and arms in a box shape with your elbows tucked close your trunk—not extended out over the water.

- When holding the paddle by the blade, wrap your fingers around the edge for a positive grip on the wet surface.

Serge Savard is a Paddle Canada sea kayaking Senior Instructor Trainer. In 2005 he completed the “Tour du golfe,” making every crossing in the gulf of St. Lawrence including Cape Breton to Newfoundland.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

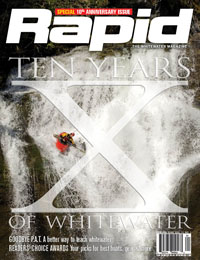

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great boat reviews, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great boat reviews, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions