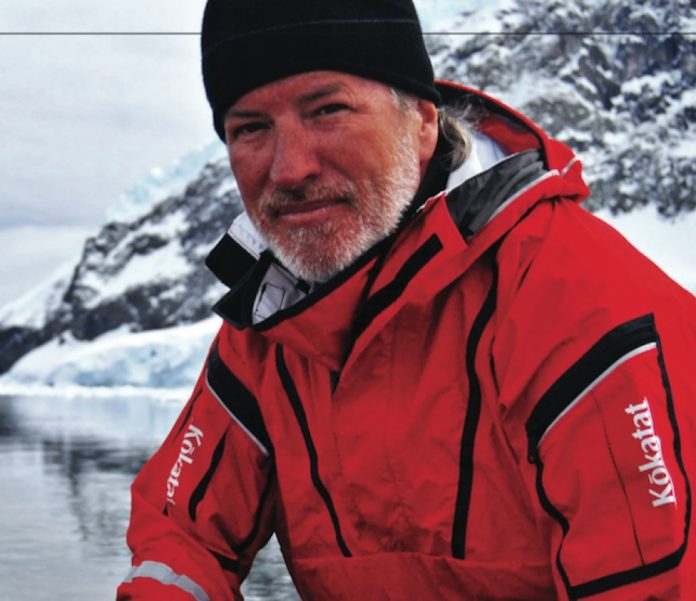

In January 2008, journalist Jon Bowermaster travelled to the Antarctica Peninsula to complete the final leg of his Oceans 8 expedition, a quest to explore all of the world’s continents by sea kayak. The Oceans 8 trips included Alaska’s Aleutian Islands (1999), Vietnam (2001), French Polynesia’s Tuamotu Atolls (2002), South America’s Altiplano (2003), Gabon (2004), Croatia (2005), Tasmania (2006) and Antarctica (2008).

Did you know that Oceans 8 was going to take 10 years when you started?

No I had no idea. When we went to the Aleutians it was just a pure, one-off adventure. It wasn’t until we’d done the second one, Viet- nam, that I thought that we should make this a long-term thing.

So how did you come up with the idea?

I was inspired by my climbing friends who had such simple and easily defined goals. I wanted some long-term project. Visiting each continent by sea kayak seemed pretty easy to me. At a sea- level way it’s our own kind of Seven Summits.

Why kayaking?

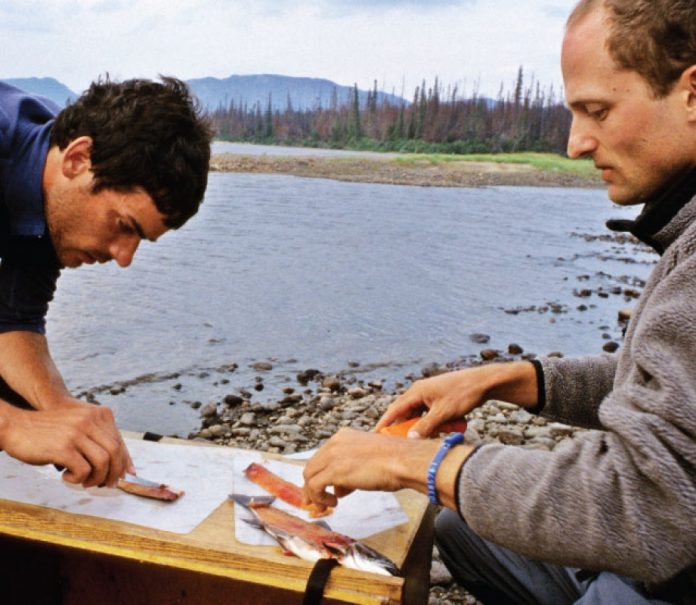

I’ve always regarded kayaks as our ambassadors. They open doors that wouldn’t open if we arrived by land. Along the coastlines virtually everyone we meet lives and depends on the sea. Everyone has a boat. Most of them are fishermen. So they don’t look at us like freaks, they look at us like brethren. Other than the Altiplano, no one ever said, “What are you doing here?”

So in South America you were just freaks?

We were dragging kayaks through the driest place on earth. The few people we did meet had never seen a kayak before. We’d rigged them on these little pull carts and harnesses. This is a place where people still believe in UFOs and extraterrestrials, so they’d see us come trundling across the desert and literally in some instances ran and hid.

In Antarctica you came across a sinking ship?

By pure coincidence when we had to drop the kayaks off in advance and I was riding on the National Geographic Endeavor, a big tourist ship, we were first on the scene of that sinking ship, the Explorer. We picked up the captain and the staff and all the Zodiacs. The captain had a guy with him who was carrying three bags—one was filled with all the passports, one was filled with the ship’s papers and one was filled with cash.

What’s next?

We’re going to South America and then Af- rica next month and the Galapagos and back to French Polynesia for other assignments.

Who’s “we”?

Fiona Stewart, my partner, travels with me, takes a lot of the pictures. She did all of the communication management from Antarctica. That’s the other part of this modern day adventuring is that it’s a lot of work. Every day you’ve got to download the images, edit the images, write the text, edit little videos.

Do you have a favourite place?

I’ve been back to French Polynesia and the Tuamotus many, many times. That might be my favourite. In a sense it’s more raw than some of the other places in that you can find people living very simply and not so removed from how their predecessors did, and it’s just incredibly beautiful.

What’s keeping you going?

Now that we’ve figured this website out and have gotten an audience that keeps checking in you really just want to keep sharing these kinds of stories—water-related and environmental-related.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2008 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great boat reviews, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great boat reviews, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2008 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.