Bruce and Chase jumped from the car and ran for the breaking waves on the beach the minute we checked in at the campground. eight hours in a car with their uncle telling tales of his past canoeing and hiking trips was not their idea of fun. By dinner, however, the car ride was long forgotten, the boys had made friends in the campground and skipped thousands of stones out into the lake. This Agawa place, they said, was looking okay.

A Lake Superior family vacation

We were camped at the Agawa Bay campground at the southern end of Lake Superior Provincial Park where Highway 17 skirts the great lake before heading inland and north to Wawa.

It was the boys who first pointed out a colourful conifer-covered headland called Rocky Point, located just a 15-minute hike south from our campsite. The next morning we scrambled up and around the point and watched the powerful waves crash into the red granite cliffs.

“Awesome,” said Bruce. “I like this hike.”

That evening we went back out to the point and watched the sunset; one magnificent enough that even Chase was touched. “How can the sun be that big?” he wondered aloud. “Does Lake Superior make that happen, or what?”

I asked the boys if they’d heard of Michi Peshu, the great horned lynx: “He is the power and mystery of these ancient waters. He might have something to do with how beautiful the sunset looks.”

Their raised eyebrows and smiles suggested they weren’t buying my story about the great horned lynx. I’d been known to exaggerate a story or two, and besides, they were 11 and 13 now—not as easily fooled as they used to be.

So the next day we hiked the Agawa Rock Indian Pictographs Trail to the old painting of Michi Peshu. It was a short hike through a deep and eerie crevice. The pictographs were painted centuries ago by native people on a high cliff overlooking Superior. We examined the mysterious Michi Peshu, and other rock paintings at the Agawa Rock pictograph site and speculated about their meaning. The boys’ fascination with Superior was beginning to show.

“We are camped on Gitchigumi,” I explained to the kids around the campfire that evening. “The ancient Ojibwa meaning is ‘great lake’. Lake Superior really is the world’s largest lake and the most spectacular too.”

“Yeah, whatever. We know all that stuff already from school,” said Chase. “Pass the marshmallows, Uncle Doug.”

The Coastal Hiking Trail in Lake Superior Provincial Park is 63 kilometres long and takes five to seven days to hike end to end. The trail traces the Lake Superior coastline along scenic cliffs, across cobblestone beaches and through bush. Those who have hiked it understand the power and beauty of Superior. I wanted the boys to experience this trail but hiking the entire trail was out of the question. We were car camping after all and were not prepared for a week-long backpacking trip.

The Coastal Trail happened to be the theme of the presentation at the park’s amphitheatre that evening. The natural heritage education coordinator, Carol Dersch knows the trail like few others. Her enthusiasm rubbed off on all of us. Best of all, Carol announced that Kathleen, her colleague, would be leading a day hike on the trail starting at Katherine Cove, 15 kilometres north of the campground. All we had to do was show up the next morning with hiking footwear, clothing and a lunch and she would lead the way.

Katherine Cove is an excellent picnic site with a shallow beach for swimming. Hikers can pick up the coastal trail and follow it north for 10 kilometres through a wilderness setting where the trail comes close to the highway again at Coldwater Creek.

We scrambled over rocks, boulders and cobblestone beaches and stopped to gaze into deep, blue, impossibly clear water and watch an otter dart in and out of a tangle of driftwood. Kathleen showed us crushed clam shells in otter scat. She pointed out all sorts of warblers and several nests while a bald eagle kept an eye on the boys from his perch in a cedar tree. She guided us to some amazing pools in the rock formed by powerful storm surge waters. She told the kids that these pools act as nurseries for frogs and salamanders—they were hooked. Kathleen told the parents about the geology—a colourful array of twisted, contorted rock mixing with smooth polished areas, pocket beaches, points and cliffs. There were multi-coloured polished agates mixed with the shoreline pebbles.

We drifted off to sleep that night with the sound of the waves softly lapping the shore and a full moon casting pine shadows on the tents. I was looking forward to the drive home because I knew it would be different. It would be eight hours of the kids telling me stories of their adventures on the shore of Gitchigumi.

Feature photo: Hans Isaacson/Unsplash

This article was first published in the Spring 2006 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

This article was first published in the Spring 2006 issue of Canoeroots Magazine.

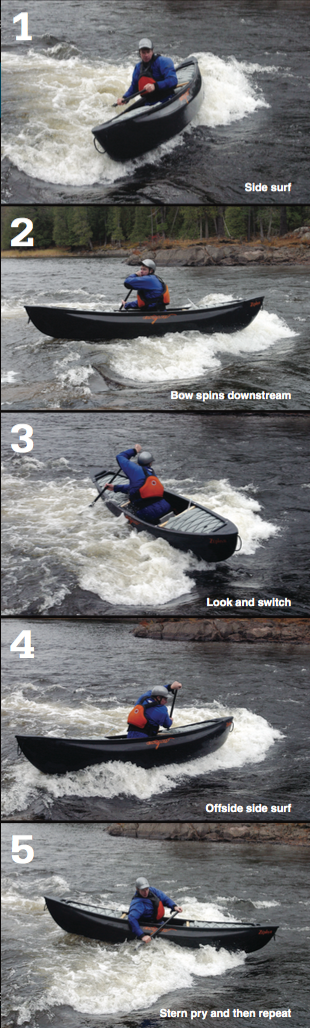

1. As you cross the foam pile, initiate an onside turn by applying a braking or ruddering stroke just behind your hip. This will get you into a side surf before your bow hits the green water coming into the hole. The green water hitting the upstream edge of your boat will try to flip you so you should have a slight downstream tilt. Side surf until you feel comfortable in the hole. Keep your strokes close to your body with an upright, balanced posture.

1. As you cross the foam pile, initiate an onside turn by applying a braking or ruddering stroke just behind your hip. This will get you into a side surf before your bow hits the green water coming into the hole. The green water hitting the upstream edge of your boat will try to flip you so you should have a slight downstream tilt. Side surf until you feel comfortable in the hole. Keep your strokes close to your body with an upright, balanced posture. This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2006 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2006 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions