I had never thought of the ice as a noisy thing. Then again, I had never paddled at the foot of an actively calving glacier. A set of unfamiliar sounds—icy groans, pops, rumbles and cracks—emanated from Greenland’s Knud Rasmussen Glacier as it fell, piece by piece, into the fjord. As my head spun back and forth following each new percussive effect, my arms were on auto-pilot, bracing against the mish-mash of waves pushing out from wherever the enormous chunks of ice crashed into the water.

Frozen assets: Paddling Greenland’s icy eastern fjords

Our group of seven had already spent more than a week paddling the Tunu district of eastern Greenland, a barely-populated maze of fjords straddling the Arctic Circle. The east side of Greenland has always been less populated than the west coast due to the huge amounts of drifting polar ice which congest the shoreline, making transportation routes unreliable.

Paddling about 20 kilometers a day in our folding kayaks, we had travelled 180 kilometers through a maze of fjords, working our way north from Kulusuk to Sermiligaq.

Along the way we had passed a handful of picturesque villages of colourful wood houses, barely clinging to the steep shoreline between the mountains and the water’s edge. It is only the coastal mountains that are habitable; the other 85 per cent of the island is blanketed by the Greenlandic Ice Sheet. At a maximum thickness of three kilometers, it depresses the land beneath and squishes out the mountains that fringe the country. Valley glaciers flow to the sea through these mountains, scouring jagged peaks and creating long, u-shaped valleys and fjords.

This icy kingdom revealed itself as I paddled beneath snow-capped mountains, beside sculpted icebergs and drift ice, to the base of immense glaciers. Despite the frozen backdrop, we were warmed by sunny, calm conditions for most of these last two weeks of July. Even mosquitoes wilted from the heat, and stayed tucked beneath cool leaves.

I wasn’t about to dismiss the mosquitoes as wimps. I’ll tip my bug hat to any insect that can survive in the midst of so much ice. Erik the Red was displaying a firm understanding of irony when he gave the misnomer Greenland to the newly-colonized island in AD 985. Perhaps the exiled Viking was trying to entice others to settle on the inhospitable island with him.

At home in Greenland, a culture in transition

Inhospitable may be a word used only by visitors. Various Inuit cultures have populated eastern Greenland’s shores on and off for 2,000 years. The Thule people arrived in the 14th or 15th century and developed the skills and customs that made survival possible, inventing the kayak, harpoon and dogsled. One of the first things I saw upon arriving in Kulusuk was an Inuit couple stretching a polar bear skin across a driftwood frame. According to Inuit custom, the hunter who first sees the bear has rights to the skin and half the meat.

While watching the enormous white coat stretch out in the sun, it was easy to grasp that the villagers of Kulusuk have only emerged from what we’d call a stone-age existence since 1958 when the United States established an international airport and radar station (truly, a cold-war outpost).

Even today infrastructure is minimal with the majority lacking running water and most using a bucket for a toilet. Chained sledge dogs, fur matted and unkempt, easily outnumber the 350 villagers. I watched my step. The dogs should not be handled, unless one is willing to forfeit a hand.

Before we set out on our trip our outfitter arranged for a demonstration of the more utilitarian origins of kayaking. Pili Maratse carried his handmade traditional kayak—sealskin stretched over a driftwood frame—to the rocky shoreline where he removed his shoes and wiggled into his custom-fitting boat.

His boat darted through a puzzle of drift ice as he showed us how to chase and harpoon narwhals and seals. Maratse’s kayak moved nimbly compared to our modern kayaks, heavily laden with highly engineered camping gear that suddenly seemed excessive.

Life here is about more than just survival. Kulusk is fortunate to have Anna Kuitse, who has been teaching village youngsters the ancient Inuit tradition of drum dancing. Dressed in a sealskin anorak and shorts with sealskin kamiks she joined Tinka Mikaelsen, a young adolescent girl with glossy, raven-black hair, clad in a white cotton anorak and an intricately beaded fringe necklace and head piece.

His boat darted through a puzzle of drift ice as he showed us how to chase and harpoon narwhals and seals.

As they danced they provided a glimpse of this art form that has died out in most other regions of Greenland. Though a particular island way of life is still somewhat intact, the ancient culture has undergone incredible changes in the last half-century. With technological and material advance comes a severing of cultural identity. Modern conveniences ease some of the hardships that come with living here, but they have the potential to break the Inuit’s traditional connections with the natural environment, detaching them from their cultural uniqueness. With global trade and communications shrinking the planet, Nike shoes and NBA t-shirts are starting to replace sealskin and polar bear garments. And with global warming making the traditional hunting and fishing lifestyle more difficult, the central pillar of Inuit culture may be facing the same fate a glacier faces when it reaches the sea.

Paddling into the funnel-shaped fjord

As soon as we left the cove in Kulusuk, we entered a fantasyland of ice. We wove our way through corridors barely wide enough for our kayaks. Bergy bits moved about at the whim of the currents, tide and breeze.

Through the process of calving and melting, each iceberg or bergy bit becomes unique. The forces of sun, wind and water combine to sculpt unique creations. Mushrooms, castles, spires, arches, triangulated slabs, ribbed platforms and circular holes bobbed in every direction. Some were clear, others white, fewer were toothpaste blue, and even fewer were translucent sapphire blue. These sapphire bergs are often younger than the white variety and appear blue because of a lack of trapped air bubbles reflecting white light.

Apart from being beautiful, the floating obstacles made travel difficult. Pathways closed in around us, causing us to retrace our path and find new routes through this icy maze. It seemed that the Tunu Fjord was simply too congested to navigate, but while we lunched on a small knoll of rock we watched the ice slowly spread apart as the tide rose. Because the fjords are funnel-shaped, the tides can be significant, often ranging between three and four meters. The increased surface area of the fjord allowed us to make progress through the sprawling gallery of ice sculptures.

I peered inside a burial chamber where a weathered human skull lay encrusted with lichen.

With the tidal currents making the fjords resemble ever-changing rivers, the trip was dictated by tidal cycles. My mindset followed along and I got used to thinking according to these short time frames. But compared to just about anywhere else on earth, Greenland is frozen in time.

We came across the ancient ruins of homes and burial sites on a promontory overlooking the Angmagsallik Fjord. Stopping to investigate, I peered inside a burial chamber where a weathered human skull, believed to be at least six centuries old, lay encrusted by lichen.

As old as this skull seemed to my New World mentality, my temporal perspective received another shock after huffing and puffing my way up a mountain overlooking the y-shaped Sermiligaq Fjord. The fjord is y-shaped with a glacier spilling into each branch, the Karale Glacier from the west and the Knud Rasmussen Glacier from the east.

Creeping glaciers return to the sea

As a curious Arctic fox hovered nearby, I looked down on the supposedly moving glacier and tried to contemplate the process by which falling snow becomes part of a glacier and gradually returns to the sea. Snow that falls on the ice sheet is compressed into ice when the weight of more snow presses down from above. As the thickness of the ice increases, the compressed snow becomes viscous, flowing through valleys as glaciers, eventually reaching the coast deep in a fjord. The process may take up to 10,000 years.

As eye-opening as the glacial panorama was, it wasn’t until we were paddling at the glacier’s terminus that I truly appreciated that glaciers are moving, active things.

After shoving off from our beach campsite in Sermiligaq Fjord, the four-kilometer-wide, 100-meter-tall face of Knud Rasmussen was an easy target. But first we had to wend our way through a glacial soup of bergy bits, drift ice and cathedral-like icebergs. Diffused sunshine glistened on these sculptures causing meltwater to trickle into the icy, inky water below.

Nearing the wall we saw ivory gulls feeding at the rambunctious base. Did the glacier’s calving stun the fish and create easy fishing? I wasn’t sure, but it was a good reminder to stay back at least three times the height of the calving wall.

We travelled as a group and listened to growls and rumbles followed by clouds of white spray, captivated by the cacophony of roars and the curiosities of deep crevasses. Huge sections of the glacier wall were a vitreous blue with deep chasms split into this wall, resembling palatial chambers.

The rumbles, growls and roars increased in frequency. Clouds of icy spray burst from the fjord below. Rolling waves spread out as larger chunks of ice spilled into the water. And then a massive, thundering bang released a sapphire chunk of ice the size of a multi-story apartment building that toppled over in slow motion. A three-meter wave spread from the foot of the glacier and rolled towards us. The fjord was alive with sounds and motion. Slurps, sloshes, crackles and slaps drowned out the sound of our rushed paddle strokes as razor sharp shards of ice engorged the fjord. Bergy bits danced all around.

We retreated, grinning foolishly, feeling reverent. The thrill of sitting at the base of a frozen wall, calving enormous chunks of millennium-old ice was pure exhilaration. Greenland was actively sharing its timeless grandeur with us, in both beauty and power.

Wendy Killoran wrote about paddling Iceland’s coast in Adventure Kayak’s Early Summer 2003 issue.

Feature photo: Wendy Killoran

This article was first published in the Spring 2005 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.

This article was first published in the Spring 2005 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2004 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Fall 2004 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

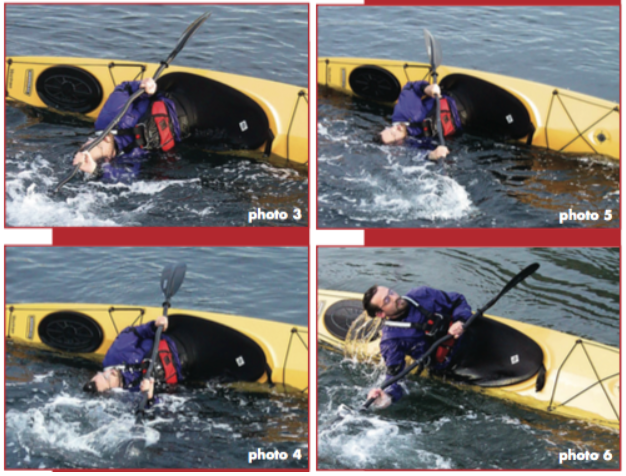

Start off practicing the scull with the kayak on a slight lean. Reaching out over the water in a high brace position, practice the sculling motion. Think of spreading butter on toast. Spreading the butter back and forth keeping the leading edge of the knife raised above the toast prevents it from diving and cutting into your breakfast. Similarly, setting this “climbing” angle on your blade ensures that the leading edge of the blade is always raised and on the surface of the water. The sweep is a long comfortable arc. Strive for minimal splash and a smooth rhythm.

Start off practicing the scull with the kayak on a slight lean. Reaching out over the water in a high brace position, practice the sculling motion. Think of spreading butter on toast. Spreading the butter back and forth keeping the leading edge of the knife raised above the toast prevents it from diving and cutting into your breakfast. Similarly, setting this “climbing” angle on your blade ensures that the leading edge of the blade is always raised and on the surface of the water. The sweep is a long comfortable arc. Strive for minimal splash and a smooth rhythm.