People kept saying I was foolish and stupid and irresponsible to quit my job every spring to go roaming in a canoe…but come spring, I’d leave. I had no sense of rebellion. I just had to go canoeing.

Where others would choose Shakespeare or Winnie the Pooh, I quoted those words from famed canoeist Bill Mason in my high school yearbook.

As an earnestly outdoorsy teenager, my dream was to do a solo canoe trip. When I finally went, I realized I’d had no idea what it would be like. I hadn’t yet learned that’s how dreams are.

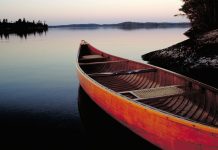

My chance came in 1989 when I was 17 years old. I had been preparing for years. At 15, I built a 13-foot solo cedarstrip canoe (see all solo canoes in the Paddling Buyer’s Guide). The day I turned 16 I applied for my driver’s licence. All winter I bored my parents with unsubtle hints about what I intended to do with the newly minted licence in my wallet. They finally agreed to loan me the family Oldsmobile three days after exams for a solo canoe trip in Algonquin Park.

I felt like a hero driving up Highway 11, the canoe firmly tied down, Neil Young, David Wilcox and The Cult blasting on the stereo. I had my own canoe, a car and three days of food and camping gear. I was free.

At the put-in, my fantasies were assaulted by a cloud of blackflies. The bugs made the first portage part backwoods blood donor clinic, part primal therapy. Going solo means there’s nobody to share the pain.

I picked up my pace and forged on. Spurred on by the flies and an increasing angst I had yet to notice, I blazed through the first day of my route in a matter of hours and reached my scheduled campsite by lunch.

My leisurely schedule worked well. Too well. It completely backfired

That’s where things started, imperceptibly, to unravel. I had imagined it would be hard to do all the camp chores myself. So I had planned a short route with more time than usual to do all the tasks that are normally shared among a group.

I had also allowed time for the quiet contemplation of nature’s majesty, since everybody knows that’s the great reward of solo tripping. Bill Mason likened the wilderness to a church, and I expected the solo experience to be a kind of rapture I would want to revel in.

My leisurely schedule worked well. Too well. It completely backfired, in fact. Eating lunch at my first campsite, I faced the challenge of what to do with the remaining 10 hours of daylight. Might as well continue paddling—just a little bit further.

Before long I arrived at the campsite I had planned for night two. This time I set up camp. I chose the site carefully—an island that was too small for bears—and set my tent right by the fire pit. I laid out my sleeping bag and my clothes. No, the clean underwear over here, next to the flashlight and the toilet paper, and a jackknife in the right tent pocket. That’s right. Then I unpacked my food and cooked some pasta, washed my dishes and put them away and hung up my food. I gathered a pile of firewood and looked at my watch.

It was only 4:30 p.m. and the sun was still high. It was one of the longest days of the year. Better make sure I’m ready for dark.

so I panicked. And then an impulsive, subconscious calculation told me what was clearly possible if I just kept moving

So I gathered more firewood and broke it into foot-long pieces. Then I stacked the pieces into piles sorted by diameter. Then I sat down and settled in for some of that quiet contemplation I’d been looking forward to. Ohmmm. Which is when I discovered that my skittish 17-year-old mind had no interest in quiet contemplation.

The wilderness was like a church all right. EXACTLY like a church, like a huge creepy vastness haunted by an otherworldly stillness. I might as well have locked myself up in an empty Notre Dame Cathedral with a “do not disturb” sign on the door. The thought of five more hours of ear-ringing nothingness, to be followed by more of the same in total darkness, felt to me like being slowly asphyxiated by silence.

I am going to die.

And so I panicked. And then an impulsive, subconscious calculation told me what was clearly possible if I just kept moving.

Within 20 minutes I had broken camp and was back on the water, now entering the territory of day three. Another portage, a few more klicks of paddling and I was back to the car. I threw my still clean gear into the trunk and tied the canoe down in a fly-addled frenzy, then sped away with the windows down to blast away the bugs.

By nightfall I was exiting the drive-thru, a Big Mac warm in my palm, and before midnight I pulled back into the driveway at home. My parents were asleep and I found my sister on the couch watching The Arsenio Hall Show.

Just act natural.

I walked in and sat down. When she asked me what I was doing there, I said, I finished my whole route. So I decided to come home.

[View all the new boats and gear in the Paddling Buyer’s Guide]

Tim Shuff eventually slowed down and enjoyed a solo trip of 25 days, measured by time, not distance. This story originally appeared in the 2008 issue of Canoeroots. Recirc is a new column sharing some of our favorite stories from the first 20 years of Rapid, Canoeroots, and Adventure Kayak.

This is one of those things in life that is just hard that you have to get through even if you expected it to be the time of your life .