Seven years ago, we published our first issue devoted to celebrating the accomplishments of female paddlers, turning the traditional—and already woefully outdated—idea that men dominate sea kayaking on its head. Women’s contributions to our sport, expression and lifestyle are so immeasurable as to make the very notion of a boys-versus-girls comparison seem, well, childish. In these pages, we’ve featured seven diverse women whose stories and talents span the entire breadth of the kayaking experience. Perhaps it’s that uniquely feminine acumen—a woman’s intuition—that guides their heads, hearts and bows in the right direction. But they share another common asset: each faces challenges with a smile on her lips. —Virginia Marshall

1 Audrey Sutherland, The Pioneer

Haleiwa, Hawaii

On a cold blustery day along the Gulf of Alaska in 1981, a sea kayaking guide named Ken Leghorn was leading a wilderness expedition around Chichagof Island when he spotted a lone kayaker in the distance ahead. The kayaker was in an inflatable boat that rode high in the water and was being half-paddled and half-blown across the choppy sea. The boat didn’t have a proper spray skirt to keep its cockpit dry, and the paddler was soaked. As Leghorn approached he saw that the paddler was a woman. She had white hair. And she was singing.

“My first reaction was, ‘This is a crazy person,’” Leghorn recalls. “I thought it must be somebody who was totally unprepared to be out there. Then I found out it was somebody who has more long-distance sea kayaking experience than I’ll ever have.”

That woman was Audrey Sutherland, solo paddler extraordinaire and epic free spirit.

Pro tip: “The only real security is not insurance or money or a job, not a house and furniture paid for, or a retirement fund, and never is it another person. It is the skill and humor and courage within—the ability to build your own fires and find your own peace.”

—Audrey Sutherland

In a kayaking career spanning five decades, Audrey has paddled an estimated 12,000 nautical miles. She racked up almost all of that mileage on long, lone voyages in the stubby little blow-up boats she adores, going solo not out of misanthropy or because she’s antisocial but because it’s just easier that way. Her wilderness sagas are not so much about getting away from anything as they are about finding simplicity, with all of the stormy weather, photogenic wildlife, idyllic campsites and cozy little wilderness cabins that go along with it.

Audrey has authored three books about her adventures. Paddling My Own Canoe recounts her earliest trips in the 1950s and ‘60s along the north shore of Molokai. Paddling Hawai’i, which came out 20 years later, is the authoritative guide to sea kayaking in the Islands.

Most recently, Paddling North, published in 2012, is the story of her longest paddle ever, an 87-day, 887-mile trek through the Inside Passage of Alaska and British Columbia. Monumental as it might have been, that particular trip was just a segment in a greater journey.

Every year from 1980 through 2003, Audrey explored the straits, inlets, fjords, islands and glaciers of Southeast Alaska and B.C. in her inflatable kayaks, racking up some 8,000 nautical miles over 23 consecutive summers. At 59, when others her age might feel adventuresome for booking a stateroom aboard an Alaska cruise ship, Audrey adopted the migratory schedule of a humpback whale, wintering in Hawaii and traveling to Alaska for the summer, and she maintained it for nearly a quarter of a century.

I met Audrey in 2012 at her beach home near Haleiwa, where she’s lived since 1956, and where we sat on her lanai watching the North Shore afternoon play out over the water. Beside us in the shade lay one of her kayaks, fully inflated and ready to go. But it had been a while since it hit the water. Audrey was born in 1922, and while she was paddling Alaska into her early 80s, nobody out-paddles age forever.

Directly in front of Audrey’s house is a surf spot called Jocko’s, a freight-train left that’s named after one of her sons, big-wave pioneer Jock Sutherland. Audrey raised four children largely on her own; her husband left for good when the kids were young. Near Jocko’s there’s a spot in the reef with a cave in it, and Audrey says she wants to get out there with her mask, snorkel and fins before the winter surf comes up. “I just want to check in on it,” she says, “make sure it’s still there.”

In her prime Audrey stood five feet, six inches tall and weighed 125 pounds. She might have tremendous stamina but she’s never been particularly strong. That’s partly why she’s drawn to inflatable boats; they’re lightweight and she can haul one up the beach unassisted. She can also roll it up, stuff it into a duffle, get on a plane and go. It doesn’t matter that inflatables go half the speed of their sleeker hard-shell cousins or that they blow sideways in the wind. They suit Audrey just fine. And they actually represent a huge advancement over her original marine technology.

On one of her earliest trips along Molokai’s north shore, Audrey had no boat at all. She put her camera, food and clothing inside a rubber meteorological weather balloon, wrapped that with a shower curtain and stuffed it into an Army clothing bag, then towed it behind her as she swam along the coast.

Paddling North describes the first time Audrey laid eyes on Southeast Alaska while flying there on a business trip in 1980. There was so much wild country, so few people and so many islands to camp on. The wheels of her mind started turning. Her children were grown and she had a little bit of money saved. She writes:

“I went home and looked at the Five Year Plan on the wall. … Paddle Alaska, number one. I walked into the bathroom and looked at the familiar person in the mirror. ‘Getting older aren’t you, lady? Better do the physical things now. You can work at a desk later.’ The next day I handed in my resignation … Sometimes you have to go ahead and do the most important things, the things you believe in, and not wait until years later when you say, ‘I wish I had gone — done — kissed.’ … What we most regret are not the errors we make, but the things we didn’t do.”

Before I left, Audrey shared a final fond recollection, something Alaska fishermen used to tell her. “They would say, ‘You’re paddling 800 miles in that?’” she remembers, bright eyes flashing with delight. “‘You must be a real nut.’” —David Thompson

David Thompson is a writer and editor based in Hawaii. This story is adapted from a feature that appeared in Hana Hou! magazine.

2 Charlotte Jacklein, The Teacher

Burlington, Ontario

“I love how much we can learn in the outdoors—about the world, each other and ourselves,” Charlotte Jacklein says of the decade she’s spent immersed in outdoor education.

Raised on a farm in southern Ontario, Jacklein and her siblings enjoyed the freedom to explore fields and forests, climb trees, wade swamps, catch frogs and forage for wild berries. “At the same time, I also had chores each day that helped develop my sense of responsibility and the importance of contributing to a greater good,” she recalls. It was a balance that would lead naturally into the rhythm of wilderness tripping.

After years teaching outside—from wilderness-based youth leadership in Ecuador to donning a bonnet and apron at a living history museum—Jacklein has recently found herself back where she started. “I never in my life would have predicted that I’d end up teaching at the same school where I was once a student,” she laughs.

In the end, it was Waldorf education’s experiential approach to teaching that lured her back into a classroom. Still, whenever she can, she takes her teaching outside. For a stormy week last fall, Jacklein lead her class of junior high students to a familiar corner of Georgian Bay for an eight-day kayaking trip around a cluster of wind-blown granite islets.

“Being out with students who I have now known for three years,” she says, “gave me a whole new perspective into the value of wilderness tripping and outdoor experiences in general.

“In the outdoors, there are natural consequences that show us whether or not we are making thoughtful choices in our actions. If we don’t peg out our tent well, we get wet. If we lily-dip, our boat falls behind. If we don’t pay attention to the camp stove, we eat burnt rice for dinner. Outdoor education promotes both life skills and academic capabilities for all types of learners, because it encourages critical thinking, creative problem solving, awareness of self and others, and resilience in challenging situations.”

Jacklein’s familiarity with her students and the Bay offered a rare opportunity for her as a teacher. “The kayaking trip allowed me to fully put my education philosophy into practice,” she says. For a wild and windy week, the students did all the things 13-year-olds do when given more freedom to make their own choices: cliff-jumping, inventing crazy games, belting out Taylor Swift songs, sleeping under the stars and eating ridiculous quantities of Nutella.

They also cooked healthy group meals, helped each other through difficulties, and displayed greater confidence, focus and organization. Many students even demonstrated altogether new capacities.

Towards the end of the trip, Jacklein put the class to a vote on whether or not to do a solo—a five-hour period of reflection where each student is alone with his or her thoughts and free from any distractions. All but one student voted for the solo.

“I found spots around the island for each student that I knew would suit them,” Jacklein says. “When I took the girl who voted ‘no’ to hers, she looked at the quiet, mossy copse of trees and said, ‘Thank you, Ms. Jacklein, this is perfect.’” —Virginia Marshall

3 Laura Prendergast, The Promoter

Port Townsend, Washington

“I have always wanted my work to be meaningful. I could never work for a company that I didn’t think was having a positive influence on people’s lives,” says Laura Prendergast of the values that lead her to Pygmy Boats. When Prendergast and her husband moved to the wooden boat mecca of Port Townsend, Washington, in 2011, she quickly put her talents in marketing and graphic design to work as marketing director for Pygmy.

Pro tip: “As with life, be open and curious to what’s around each corner. You don’t have to do something epic—adventures can be had in your own backyard. ‘The world shall perish not for lack of wonders, but for lack of wonder.’” —Laura Prendergast

“I heard about Pygmy through the documentary Paddle to Seattle, and I thought, ‘Now that is cool,’” she recalls. “Empowering people to build their own kayaks and then get outside on the water.” Here was a company that understood the feeling she had first experienced as a teenager backpacking in the Colorado Rockies—something profoundly fulfilling and very much in opposition to the predominating materialism of her profession.

A native of the Texas Hill Country transplanted to the coast by way of the mountains, Prendergast is relatively new to kayaking, but she’s driven by the healthy lifestyle paddling promotes. “It’s more of a sociological phenomenon that I feel I’m participating in,” she says of her work as a promoter of the sport. “We have become a culture that no longer builds anything. We buy large houses and then we buy pre-made stuff to fill them.” Through her work at Pygmy and her own life choices, Prendergast is bucking the trend.

She and her husband are building their own 430-square-foot house in Port Townsend. Although it’s not as close to the water as the tiny cabin she had been renting on the coast, from where she regularly kayaked the six miles to work—“It was difficult in the winter when it was dark, but I could paddle one way and take the bus home”—she’s still able to make a fossil fuel-free commute. “It’s a lovely walk,” she says, “but I do miss the porpoises.” —Virginia Marshall

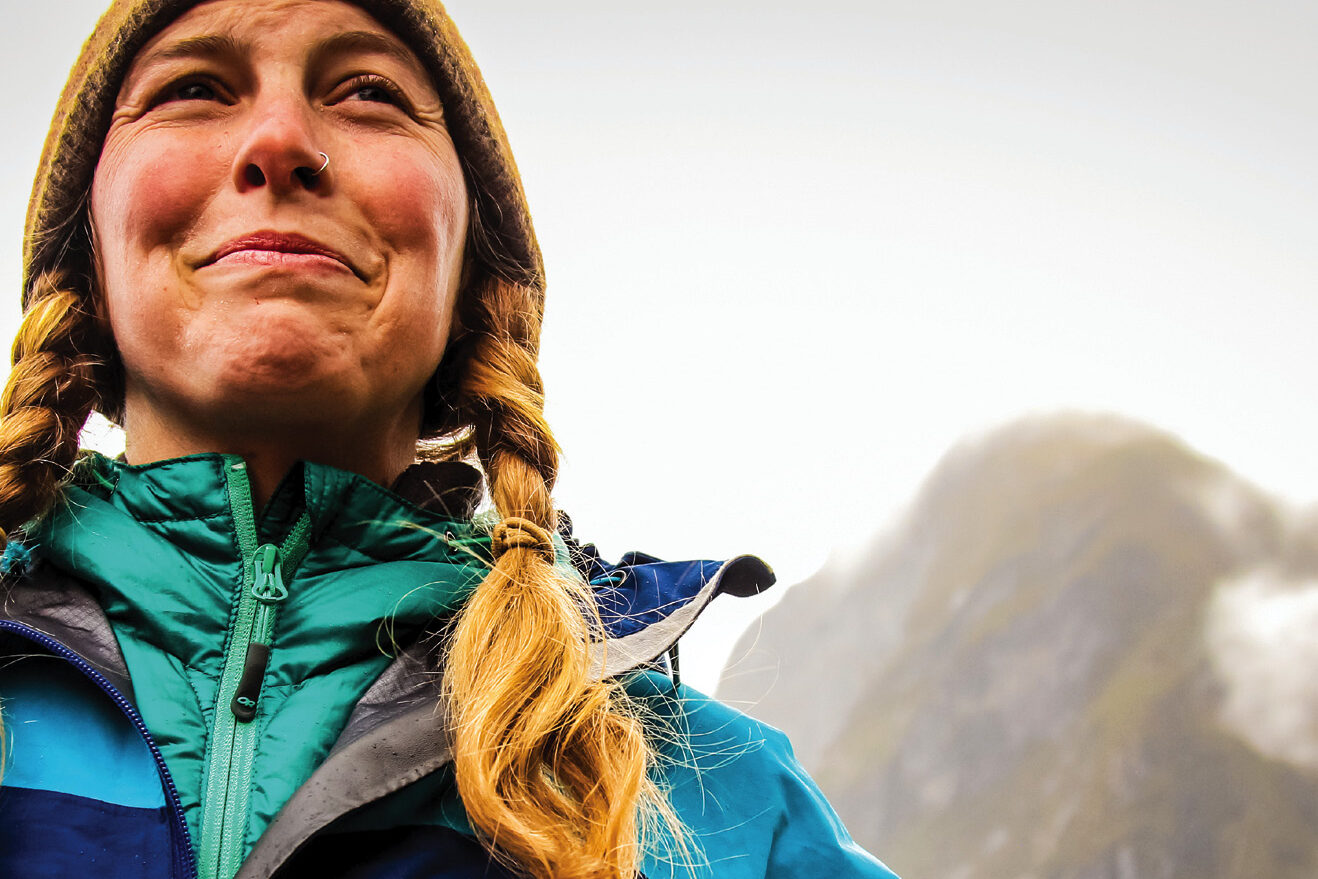

4 Tara Mulvany, The Nomad

Te Anau, New Zealand

So says Kiwi adventuress Tara Mulvany of the urge that launched her on a two-year odyssey paddling around New Zealand and Vancouver Island. With a three-month tour of remote Fiordland already under her belt—during which she and boyfriend Sim Grigg were pinned down for 14 days by gale-force winds and eight-meter seas, nearly running out of food—the then 23-year-old sea kayak guide felt up to the challenge.

“I wanted to live simply, where the wind and swell are what matter most.”

With her willowy build and girlish giggle—“I’m pretty sure Tara giggled her way around New Zealand,” says admirer Laura Prendergast—Mulvany isn’t your archetypical stoic seadog. “She’s a cute, skinny thing who paddles barefoot,” notes expedition paddler Justine Curgenven. She’s also sprinted naked down “more beaches than I can count on my fingers and toes” as a means of bear deterrent, and navigated large tracts of coast with just a road map. Lack of footwear and charts aside, Mulvany’s faded paddling jacket and threadbare PFD are testament to her time on the water.

For Mulvany, who grew up climbing mountains and trekking with her parents, a winter circumnavigation added to the trip’s appeal. “No one had ever paddled around the South Island in winter before,” she says.

In May 2012, she and Grigg set off on what would prove to be a life-defining journey. Seasickness, surf landings in the dark, capsizes and even getting separated for several days on the wild West Coast tested their commitment to the trip, and each other. Halfway through, Grigg left for good. “It was a strange feeling to leave behind the security I had felt with having a companion and face the uncertainty ahead alone,” she says of her decision to continue solo.

Intoxicated by the simplicity, freedom and challenges of life in a kayak, Mulvany went on to circle the rest of New Zealand, tracing the coastlines of Stewart Island and the North Island on a journey that was by turns idyllic and epic. She recalls one stormy day when she paddled for nine hours only to be forced back by deteriorating weather to where she’d started. “It was one of those days when I didn’t care that I’d gotten nowhere,” she says, “I was thankful just to be on land.”

Pro tip: “You don’t have to be a hardcore paddler to set off on long epic trips. If you break up big trips into achievable legs you’ll be surprised how quickly new milestones slip by.” —Tara Mulvany

Mulvany says it’s this ability to play the conservative card that makes women such successful expedition paddlers. “I made it because I followed my instincts, listened to fear when it was necessary, and waited for the conditions that I knew I could manage,” she says. “So much can be gained from adventuring solo—it’s easy for women who paddle with men to just follow, and not be actively engaged in the decision-making process.”

The reward to facing challenges on your own terms and overcoming your fears, Mulvany says, is greater confidence and contentment. The pain of numb hands and empty stomach, the aching muscles and occasional loneliness—what she calls “character building moments”— fade with time. “I’m glad that I gave it my best shot,” she says, “I can look back at those and just giggle.” —Virginia Marshall

Read about Tara Mulvany’s South Island circumnavigation in her book, A Winter’s Paddle. This summer, she’ll be attempting a first-ever circumnavigation of Arctic Norway’s Svalbard Archipelago—with three men.

5 Kristin Gates, The First-Timer

Boston, Massachusetts

I was not afraid until I heard the roar. At first I refused to acknowledge what the growing sound was. It must be the angry growl of a chainsaw, or perhaps a jet. I promised myself that it couldn’t be the sound of the water ahead, but even before my kayak turned the next bend, I knew it was. I was heading into the Yukon River’s legendary Five Finger Rapids and there was no going back.

It was the first month of a 2,000-mile journey retracing the Klondike Gold Rush route and beyond. I had traveled four days by ferry up to Skagway, Alaska, and then hiked the Chilkoot Trail through the Coast Mountains to Lake Bennett. From there the plan was to paddle the Yukon River all the way to the Bering Sea. It was a trip that I had planned with a partner who knew a lot more about river travel than I did. A partner who, two weeks before the start, had to choose work over the river.

I had barely been kayaking before—never overnight—and nearly decided to call it quits before even starting. There were plenty of things to be afraid of: whirlpools, high waves, wind, drowning, hypothermia, but most of all I was afraid of being alone. What business did I, a girl raised in East Coast suburbia, have on the mighty Yukon solo?

But in the end I knew that if I didn’t kayak the river now, I was in danger of never seeing its length. Of never following this dream and having to live with that disappointment. Having to always wonder “what if?” Growing old with “what ifs” sounded more painful than anything.

Five Fingers is so named because the Yukon narrows drastically at this point and an enormous volume of water is quite suddenly squashed into five different channels over reefs and around towering islands of rock. Above the rapids, my head filled with the stories I had read about these treacherous waters. According to one gold rush traveler (who was perhaps prone to hyperbole) it was the responsibility of every miner who survived Five Fingers to pause after the angry water and dig a grave to bury one of the unlucky.

Oh boy.

I paused for a moment in an eddy to collect myself. My life vest was strapped tightly, my gumboots were off (no good having those things weighing me down if I ended up swimming in ice water) and my emergency bag was ready to go. Okay. One, two, three… and I dipped the nose of my red Folbot Kodiak into the muscular current. How high were those white waves? Three feet? Four feet? Twenty feet?

Why I do it: “For months, for hundreds of miles, you have this wonderful purpose, this single goal to work towards. It is your job to see the world, to learn from the wild.” —Kristin Gates

A strong current punched from the left and I fought back to keep the boat heading downstream. Tearing past the islands and cliffs and reefs into wider river, riding the waves like a champion. It took me until halfway through the rapids to realize…this is fun! I let out a “WHOOP!” and flew down the river into the evening feeling alive.

I fell asleep in love with it all. With the new challenges and daily lessons. A lesson on navigating riffles, a lesson on avoiding whirlpools, a lesson from the wolves and bears and gulls, a lesson on the surprising goodness of kindly strangers.

I’ll tell you the big secret. The trick to these long-distance expeditions is to forget the end entirely, to lose yourself in the adventure. You can’t look at the whole picture. Two thousand miles of paddling—that’s impossible! Little step by little step, stroke by stroke and then, all of a sudden, you will see that all of these tiny efforts can add up to something great and you can do the impossible.

I headed out to the headwaters of the Yukon knee-shaking scared, and what do you know, it turned out to be one of the greatest adventures of my life. Months later, I did reach the coast, but the end goal isn’t the point. You don’t hike the Appalachian Trail just to summit Katahdin, you don’t trek the Continental Divide Trail to see that slab of concrete at Crazy Cook, and you don’t paddle the Yukon to see the Bering, just like you don’t live to die. It is the journey that is everything.

Trade the couch for adventure. Trade inertia for wildness. Trade comfort for life. —Kristin Gates

Kristin Gates is an accomplished long-distance hiker and dog musher; she is the first woman to traverse Alaska’s Brooks Range solo. She blogs about her adventures at milesforbreakfast.com.

6 Justine Pechuzal, The Artist

Seaward, Alaska

After supper we headed out to watch Adrian butcher the seal. On a small wooden table, a sharp knife made quick work of violet crimson flesh, soon to be hung on the willow branch frame where four-dozen strips of meat had already dried and blackened in the cold Arctic air.

I initially traveled north to work as a seasonal sea kayak guide, never imagining that Alaska’s great wilderness would afford artistic employment. Yet the more I explored the landscape, the more I filled the pages of my journal, eventually spilling imagery into larger formats like canvas and murals. The art I created spoke of animals, plants and places: life-size humpback whales enlivening an abandoned lot in downtown Seward. Five Finger Island, where abundant wildlife inspired watercolor, ink, oil paint, pencil and pastel; and where lighthouse chores, restoration projects and paddling exploration occupied the days of a five-week artist residency.

With persistence, I found jobs helping communities voice their experiences, culture and environment through public art. They, in turn, taught me about their lives.

Before leaving Adrian’s yellow-sided home, my hosts offered a sample of pickled whale blubber. Sharp sour taste, spongy texture; hard to believe I was consuming an animal of power and grace whose species I often admired while paddling and replicated in paint. For these subsistence-based Native people near the Bering Sea, wilderness inspired, but more importantly, it provided.

That week, White Mountain School students and I painted images of rivers and mountains and moose. We displayed our work for the community, and then I began the long commute home. In a few months, it would be summer, the return of humpbacks from Hawaiian sojourns and fine weather for kayaking in my backyard fiords.

In the middle of almost every mural project—students uncooperative, design a mess, and logistics overwhelming—I swear that this one is the last. Uncertainty defines my work, from the blank piece of paper, to the next job, or how many weeks I will be away. Why do it? Why do Native people eat seals when they could buy frozen hamburger patties? It has to do with feeding the heart as well as the stomach. —Justine Pechuzal

Justine Pechuzal grew up amongst the spiny cacti of Arizona, where she earned a Masters in Art Education. Her artwork reflects her intimate and playful relationship with wilderness.

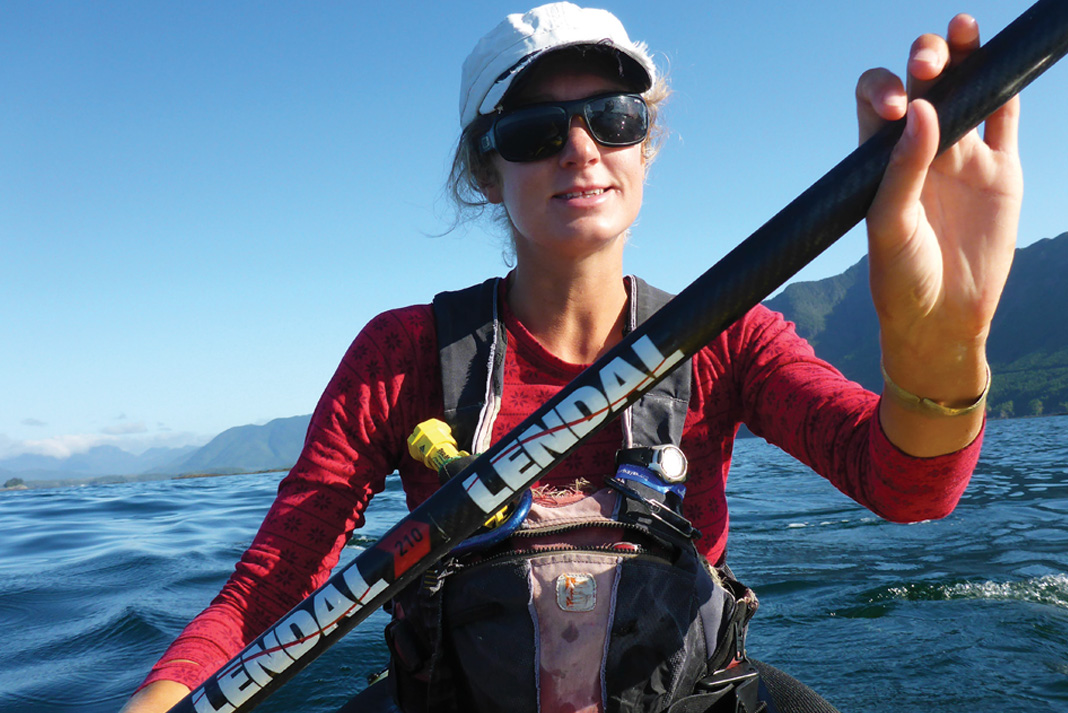

7 Sarah Outen, The Earth Roamer

United Kingdom

Sarah Outen’s late father once described her as a carthorse—strong, dependable, good natured and capable of going on forever.

These traits served her well in 2009, when she became the first woman and the youngest person to row across the Indian Ocean, just a year after her father’s passing. Focusing on the challenge helped Outen cope with her grief, and she soon set her sights on an even more formidable goal.

Over the last three years she’s paddled, pedaled and rowed three-quarters of the way around the world on a journey that will take her 20,000 miles back to her starting point in London, England.

In 2012, attempting to row solo from Japan to Canada, she encountered a severe storm and spent 36 hours strapped in her tiny cabin, her breath catching every time she capsized, watching more and more water seep into her living space, realizing the boat was taking longer and longer to right itself. Outen was rescued by the Japanese coast guard, her boat was lost at sea and she returned home to England suffering from depression. The carthorse sought help, found another boat and continued the next year with a characteristically positive attitude.

“You can’t be totally set on your original plan and take it as a failure if it doesn’t work out,” Outen says. “If there’s a way to evolve with changes, to pick up and carry on, then really embrace that. Being open to the magic of those changes can bring some of the best experiences of an adventure.”

Pro tip: “Be prepared and get sensible advice, but don’t get held back by fears of this, that and the other. Just have a go.” —Sarah Outen

The plan evolved again in 2013. On her second attempt to row the Pacific, currents and winds blew her away from Vancouver. She diverted to Alaska’s Aleutian Islands, and returned in 2014 to kayak 2,500 kilometers along the remote volcanic chain and the Alaska Peninsula. At the first road, in Homer, she climbed on her bike to cycle across North America in the winter. Her last leg is rowing the Atlantic back to London this summer.

“I don’t just like it—I love it,” she explains. “I love the human powered element, being out in the wild, experiencing new things, new places, new people.”

I joined Sarah for the kayaking legs of her journey, including the wild and challenging Aleutians. Despite very little rough water kayaking experience and a very new flatwater roll, she endured 16-hour paddling days, intimidating tidal rips, daunting crossings and currents that swept us away from the safety of land. We were hundreds of miles from help, yet she summoned the mental strength to keep going when she was scared. In 101 days, we only exchanged heated words a few times. Outen doesn’t hold grudges, her philosophy is simple:

“When times are tough, I focus on good things about the day. If you spend all your energy being negative, you’re not going to be very productive. You can let the negative stuff have a bit of a shout to get it out of your system, then focus on the positive, even if it’s just thank goodness the day is over.”

The carthorse has evolved herself during the journey. She’s now engaged to farmer Lucy Allen and looking forward to getting back to the UK for her wedding. “It really enriches your understanding of the world and your perspective,” Outen says of her earth roaming. It may seem counterintuitive, but she says life on the move “has helped me to become more balanced, more settled.” —Justine Curgenven

Justine Curgenven’s documentary of the Aleutians journey is available now at cackletv.com.

Feature photo: Doug Elsey

This article was first published in the Spring 2015 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.

This article was first published in the Spring 2015 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine.