Renowned nature artist and wildlife advocate Robert Bateman calls southeastern British Columbia’s Columbia River Wetlands “one of the most precious things on a world scale,” and he is among thousands joining the call to protect this critical wildlife habitat from increasing threat of fast-moving, noisy, motorized recreation activities such as jet boating and jet skiing.

This 180-kilometre-long wetland complex forms the headwaters of the Columbia River and is one of the largest intact wetlands left on the continent. Filling the Rocky Mountain Trench between the towns of Canal Flats and Golden, B.C., these wetlands are particularly critical to both migratory and resident birds and wildlife.

The Columbia River Wetlands were designated wetlands of international significance under the Ramsar International Convention on Wetlands. They also join South America’s Lake Titicaca, Siberia’s Lake Baikal, Eastern Africa’s Lake Victoria and nearly 50 other water bodies in the Global Nature Fund’s Living Lakes Network, an international conservation network dedicated to the protection of water resources.

AN ACCEPTABLE COMPROMISE

In response to nearly 10 years of effort by local canoeists, hunters and conservationists led by a local non-profit, Wildsight, Transport Canada is finally poised to impose regulations to control unsustainable motorized recreation activities in these wetlands.

The proposed regulations include a ban on waterskiing and powerboat operation in the wetland portion of the system. However, pressure from motorized users has stalled protection measures for the Columbia River main channel—a central habitat feature of the wetlands.

The initial proposal, which included a ban on all motorized use of the river during critical spring and fall wildfowl staging and nesting periods, was shot down by motorized interests, who earlier launched a lawsuit to rescind a 10-horsepower limit imposed by the Province of British Columbia, based on the premise that the river is a navigable waterway, and therefore under federal jurisdiction.

Now up for debate is a proposal for a year-round 20-horsepower limit on the river.

“We see otters, beaver, heron, eagle, waterfowl with chicks, songbirds, moose and bears using the main channel, and it is one of the few remaining opportunities for non- motorized recreation in this region,” says Maryann Emery with the Golden Outdoor Recreation Association, who has been canoeing the Columbia for over 30 years.

“Our members would like to see a complete ban on motorized use of the main channel, but the 20-horsepower limit is an acceptable compromise,” concedes Emery. “This place is an unbelievable treasure, both from a wild- life and quiet recreation standpoint, and we need to act now to protect it, not just for us, but for the future.”

Transport Canada says they will make a final decision on the future of the Columbia River main channel and its wildlife sometime in 2010.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Canoeroots Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Canoeroots’ print and digital editions here.

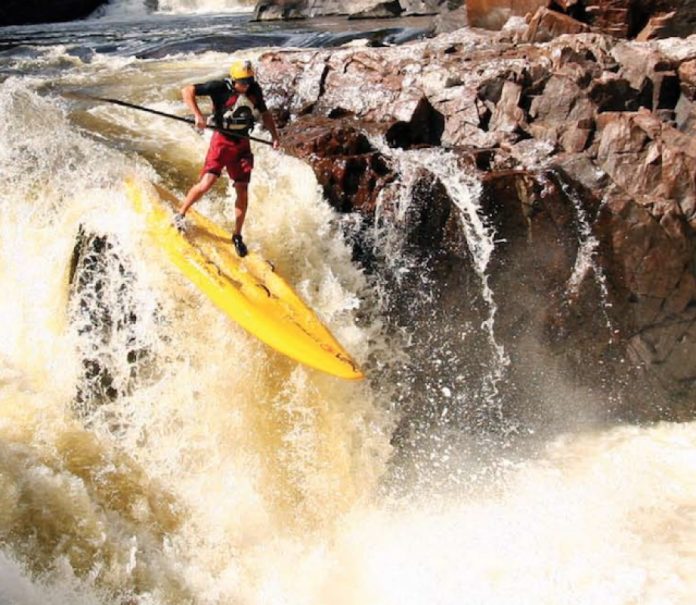

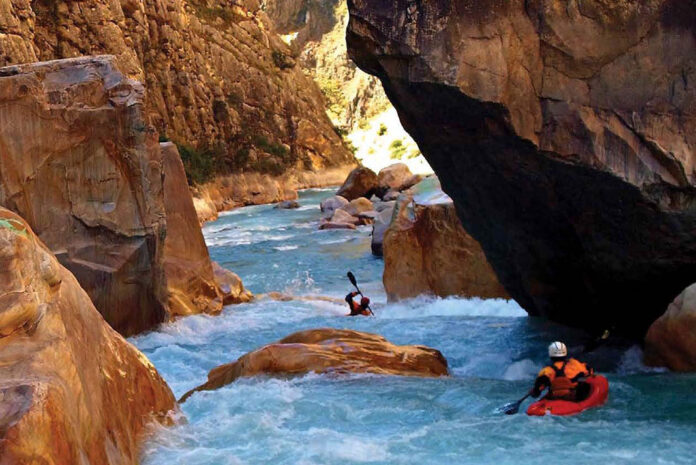

This article first appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article originally appeared in Rapid’s Spring 2010 issue.

This article originally appeared in Rapid’s Spring 2010 issue.

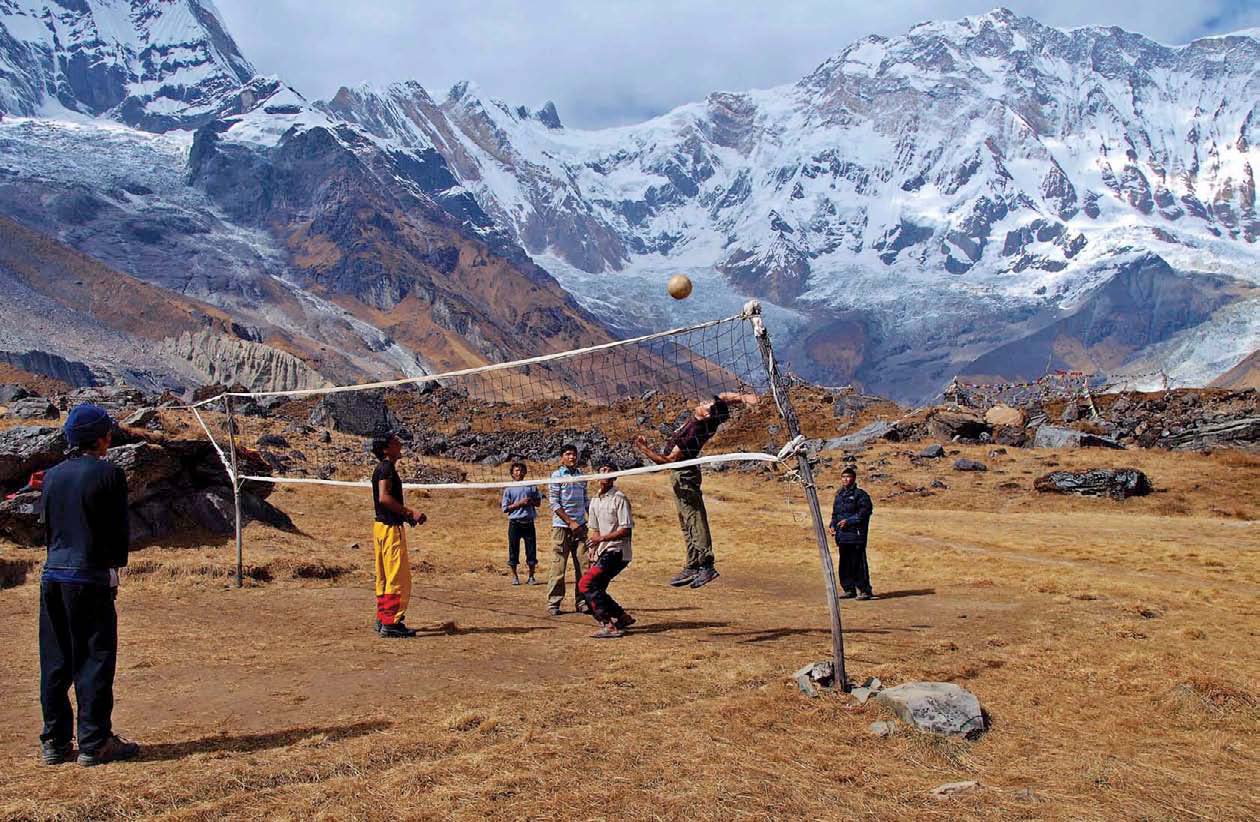

This article first appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine as part of a feature on kayak dream homes. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine as part of a feature on kayak dream homes. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions