Struggling to keep a grip on my 90-pound kayak, I tried to anchor it to a tree. No luck; the weight of the fully loaded boat started to drag me down the rotten incline until my legs jammed underneath a log and a stick probed me in an unmentionable place.

All humor had long since tumbled into the gorge below, along with untold amounts of loose scree. We were seven hours into a portage around a 50-meter section of Siberia’s Chebdar River. I gripped the grab loop as if it were my own sanity. If I let go the boat would have plummeted thousands of feet back to where this ridiculous journey began, stranding me in the middle of the Altai Mountains with only a paddle.

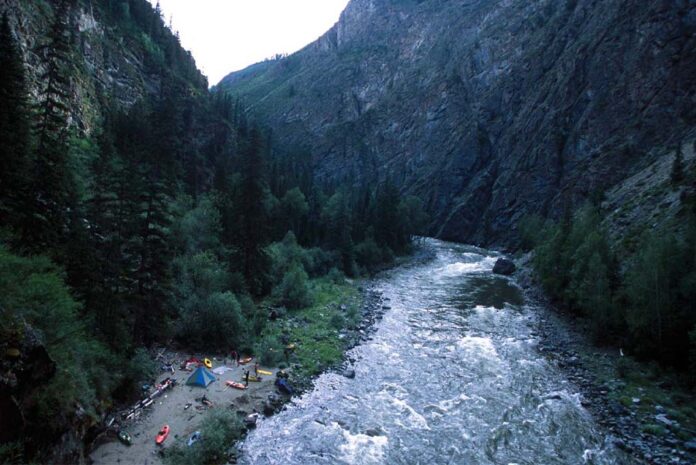

Hard labor on Siberia’s Chebdar River

It was the fifth day of our six-day, self-supported first descent of the Chebdar. To get to the put-in we had hiked two days over ground so rough the pack horses we had hired were turned around by their owners. The morning broke with the typical schedule of coffee, energy bars and talk about what lay ahead—except today we didn’t know what lay ahead. The river had been attempted by raft twice before. Both parties had met unnavigable gorges, abandoned their missions and gear, and walked out.

After two quick kilometers, a canyon pinched the river into a horrendous maze of terminal holes and exposed rocks that funnelled the angry water through woody sieves. The final section pushed itself through a two-meter gap between cliffs that fell straight into the river. Our only option was to climb.

Mountain climbing with kayaks

It was early—11 a.m.—and I assumed we’d find a route above the gorge with a few hours of portaging. That optimism slipped away with every step. The climb began on as steep a slope as trees can grow on, each step sunk knee-deep into decomposing vegetation. Three labored hours later the trees thinned and I turned my head to see the canyon wall close on the other side of the gorge. I tied my boat off to a tree and it hung nearly suspended in the air. We were now on a climbing expedition with kayaks—people and boats were to be on belay or tied off to anchors at all times.

We pooled every piece of climbing gear we had and followed the most obvious way forward, a three-pitch traverse that ended in a highly exposed dead end. Russell Kelly free-climbed straight up on a scouting mission using the hanging vegetation to aid his ascent. A long hour later he came swinging back down like a clothed Tarzan: “It’s a long, long way up. But I made it to the top and found a ravine that goes down. No guarantees but it might get us down to the river.”

Three hours into the portage and we were less than half way to the top. Every water bottle was swinging empty at the end of its clip. The possibility that we’d descend back down to the river only to find more impassable sections nagged at me like the neoprene rubbing on my blisters. We had little information about what was downstream. Russian paddlers told us it looked runnable, but that was only from map and aerial scouting.

After three pitches, the steepness mellowed and we began shouldering our boats toward a saddle as dusk fell. I reached it last and came across a desperate scene. Five dirt-encrusted figures were bent over and panting dryly through mouths that hadn’t tasted water in hours.

A sleepless night on scree

Though skeptical about blindly descending, we couldn’t stay put so we began lowering the boats through a steep tree-choked ravine. Four rope lengths later we came out at the top of a scree field. For the first time in hours I could hear the river below.

Camp was destined to be at the base of the scree field, above the lip of a cliff that faded into darkness. Pruzan and I followed the beam of our headlamps toward the sound of some running water coming out of the cliff below. I anchored myself to a tree and slowly lowered Pruzan across a descending traverse to a rivulet where he filled up all the water bottle and a big drybag. Nothing will ever taste as good.

Relief overcame fatigue when Wilson’s whistle put an end to the few hours I spent in my tent wondering which of us would be crushed or swept off the cliff by the talus that was still adjusting to having been disturbed for the first time by six clumsy humans.

Back to the business at hand

After a meager breakfast, we got back at it, traversing along the rim of a cliff until we found a five-hour route down to the river through another scree field as a thunderclap announced a downpour of rain. We arrived back to the river at 11 a.m. after 24 hours spent getting around 50 meters of river.

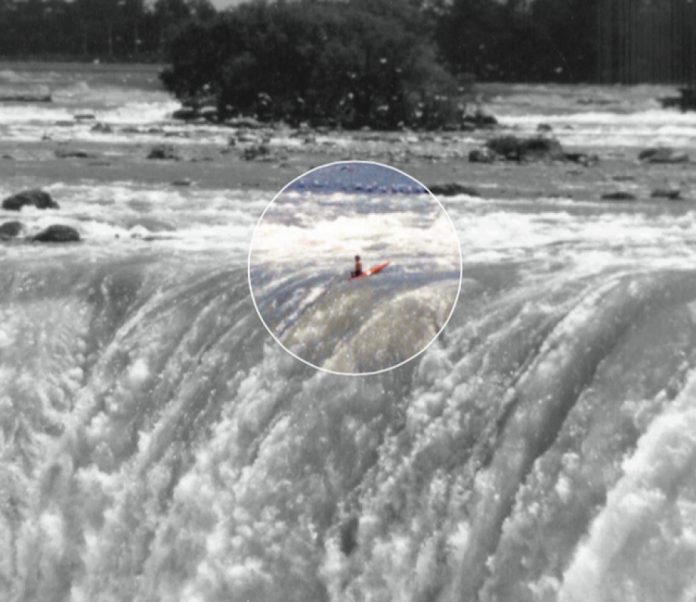

All we could see downstream was a class VI rapid that led into a thin gorge. There didn’t seem to be any way to scout it, but it didn’t matter. Portaging again was out of the question.

Seth Warren was joined on the Altai expedition by Russell Kelly, Aaron Pruzan, Matt Wilson, Ryan Casey, Evan Ross, Adam Majors and Nick Turner.

This article originally appeared in Rapid’s Spring 2006 issue. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.

This article originally appeared in Rapid’s Spring 2006 issue. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.

Baskaus River, day 1. “The Baskaus has been run since the 1970s. We assumed it would be a good warm-up for the more remote Chebdar River. I wish we had a warm-up for the warm-up.” | Feature photo: Seth Warren

This article first appeared in the Spring 2006 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2006 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article was first published in the Spring 2006 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine and was republished in the 2023 Paddling Trip Guide.

This article was first published in the Spring 2006 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine and was republished in the 2023 Paddling Trip Guide.