Ottawa is home to all things truly Canadian: Winterlude and BeaverTails, the Ottawa Senators hockey team, the Liberal government and, best of all, Back Bacon.

Don’t start your mouth watering just yet. Back Bacon is a fantastic park-and-play spot near the heart of downtown, and practically across the street from Carleton University.

“It’s like [the Ottawa River’s] Push Button on steroids,” says local Mark Dubois, who “re-found” the hole last year and began spreading the word. “It’s a real asskicker—a full-on strap-the-helmet-tight kind of hole, great for loops, ends, splits, whatever you’re into!”

Back Bacon is at Hog’s Back, the place where the manmade Rideau Canal splits from the natural course of the Rideau River. The canal goes through the Hog’s Back Locks, and the natural river carries on over a series of limestone falls and rapids and then flows for about five more kilometres to dump into the Ottawa River next door to the PM’s house on Sussex Drive.

A historical plaque nearby says that Hog’s Back was named by hungry loggers after a humped rock in the rapids that reminded them of swine. The rock disappeared during construction of the Rideau Canal back in the early 1800s. However, there’s now a McDonalds just around the corner on Prince of Wales Drive, so you can call it even.

Hog’s Back consists of one class V waterfall with multiple lines and three class III rapids below the falls. The falls were popularized by Mark Scriver and Paul Mason in their book Thrill of the Paddle. Shortly thereafter, up-and-coming hair boaters were making it a prime target for conquest, with some mixed results. In 2002, a few paddlers were charged with trespassing on National Capital Commission (NCC) property. They won in court because they had stayed in their boats and didn’t actually set foot on the NCC’s restricted riverside. So it’s all perfectly legal—just don’t go scouting the drops from the other side of the black fence.

Three channels emerge below the falls. The far river-left channel has the most flow. Halfway down this channel are two frothy, deep and powerful play holes with small eddies. The second, main hole, Back Bacon, is marked with a sign in the eddy. Local legend has it that the sign has always been there, but if you ask Dubois, he might fess up.

Back Bacon is a demanding hole that’s capable of pounding you silly— making it unsuitable for beginners—but will reward most intermediates with fast, exhilarating rides.

The key to Back Bacon is to paddle hard. It’s quite powerful in the spring. You need to be aggressive when throw- ing moves and when you flush off, pad- dle just as hard to catch the small eddy. Local boy Nick Miller says:

“It’s a great spot for pretty much every hole move. Nice and sticky without being hard to manoeuvre in. It’s deep too…. The spot favours righties a bit, but you can definitely huck both ways ’til you’re dizzy. It’s a great spot for loops and it’s even retentive enough for tricky whus.”

If you’re in the Ottawa this spring make sure to stop by for some really good hole boating. It doesn’t get any more Canuck than this, so you’d better apologize if someone bumps you off the wave!

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2004 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2004 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2004 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2004 issue of Rapid Magazine.

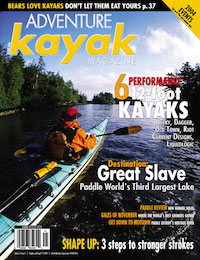

This article first appeared in the Spring 2004 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2004 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions